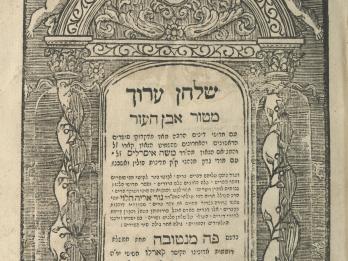

Bet Yosef (The House of Joseph): Introduction

Joseph Karo

1542

Introduction

Blessed be the Lord, the God of Israel, who created His world for the purpose of mankind, and, from all the different sorts of men, chose for Himself a nation as a special treasure—namely Jacob, the lot of His inheritance (Deuteronomy 32:9); and out of the abundance of His love for the people close to Him, He brought us near to Mt. Sinai and gave us as our heritage, through the medium of the choicest of the human race, Moses our teacher—peace be upon him—the Torah and commandments, righteous statutes and ordinances [see Deuteronomy 4:8] for our benefit, in order that we may walk in His ways and find favor in His sight. But it came to pass that, after the lapse of a lengthy period of time [see Genesis 26:8], we were [so to speak] “emptied from one vessel to another,” as we went into exile, and we suffered from numerous tribulations bound up with, and following immediately one upon another, to the point where, for our sins, [the prophecy:] And the wisdom of its sages shall perish, etc. (Isaiah 29:14), duly attained its fulfillment through us. And the power of the Torah and of its students became exhausted, for the Torah did not become merely like two distinct Torahs, but rather like an infinite number of Torahs, on account of the multiplicity of works that came into existence on the interpretation of its ordinances and its laws. And notwithstanding the fact that they [the sages], peace be upon them, had the intention of illuminating the darkness surrounding us, there emerged nonetheless, out of that goodly light from which we derived benefit from them, peace be upon them, doubts and immense confusion, in that each individual composed a work on his own account, and simply reiterated what his predecessor had already written and composed, or alternatively set forth the law in question as the reverse of what had been recorded by his fellow man, without making mention of what the latter had said. For one will find quite a number of poskim [halakhic decisors] citing a particular law anonymously, as though it represented the universal consensus, without any dissenting views; but when you come to research the matter, you will find that great authorities are in dispute over it, as is plain, from countless instances, to anyone who has delved carefully into the works of the decisors and has looked into the source of the relevant statements in the Talmud and the early commentaries:

Now if a person were to say, in regard to each halakhah, that it is necessary for him to investigate its source and discover it in the words of the Talmud and all the commentators and decisors, this would prove a most burdensome task for him. How much more so would this be the case where he wearies himself out in “finding the door” [see Genesis 19:11], that is to say, in getting to know the place in the Talmud where the law in question is to be found. For although the Holy One has granted us the merit of having the explanations of the master, the Maggid Mishneh [Vidal of Tolosa, late 14th century] of blessed memory, and to the compilation of Rabenu Yeruḥam [ben Meshullam (ca. 1290–ca. 1350)], which guide us in regard to the sources of the laws in the Talmud, nonetheless anyone delving into these will soon become aware of and recognize his limitations should he not possess a comprehensive knowledge of the Talmud. And moreover, in numerous cases, he will search, but be unable to find within their words any source for that particular law. [ . . . ]

And if this is the case where a person just happens to become involved with one specific law, then, where an individual wishes to know the origins of all the laws in their clarity and to encompass the words of all authorities who take issue with them, as well as the distinctions that are contained within the words of each and every one of them, how much more so will he be incapable of acquiring such knowledge! For even if he were to research, in regard to every single law, the words of the Talmud and the commentators, and the words of all the decisors‚ which involves going to an exceedingly great amount of trouble—as forgetfulness is common among human beings, and is most certainly prevalent in relation to matters with manifold ramifications—he will thus be found to have labored in vain, heaven forbid!

Accordingly, I, the most insignificant member of my clan, Joseph, son of our teacher, R. Ephraim, son of our teacher, R. Joseph Karo—may he be remembered for the life of the world to come—have been zealous for the Lord of Hosts [see 1 Kings 19:10], and have bestirred myself [see Nehemiah 5:13] to clear the pathway of obstacles; and I have therefore seen fit to compose a work incorporating all the laws and customs currently in force, by elucidation of their sources and their derivation from the Talmud, together with all the distinctions made in the opinions of the various decisors, not a single one having been omitted. [ . . . ]

I have seen fit to connect this to the work known as Arba‘ah turim (Four Columns) authored by the master, R. Jacob ben Asher [the Tur (1269–1343)] of blessed memory, as it incorporates the majority of the opinions of the decisors.

Now the purpose of my work and its function is as follows—to elucidate the halakhah recorded by the author of the Turim, to determine whether it is derived from a Mishnah, Baraita, Tosefta, or from a statement appearing in the Babylonian or the Palestinian Talmud, or the Sifra, Sifre, or Mekhilta—and whether it is accepted universally or is a matter of dispute among Tannaim [authorities of the Mishnah] or Amoraim [authorities of the Gemara] in such instances where the compiler determined the halakhah in accordance with the view of one of them, and his reason for having done so. [ . . . ]

And there have now come into my possession an explanatory commentary on the major part of the work Oraḥ ḥayim, authored by our great master, R. Isaac Aboab of blessed memory, as well as a commentary to the first part of the book Oraḥ ḥayim and to the first part of the book Yoreh de’ah, written by our teacher, R. Jacob Ibn Ḥabib of blessed memory. And I have seen fit to cite their words in their own name, and wherever it seemed appropriate to me to dissent from their views, I shall set forth those aspects of their statements with which I find difficulty, and I shall record my own view, and the person researching the issue may select whichever seems best to him. And, since the work Arba‘ah turim is replete with scribal errors, I shall, in quite a number of places, point out those instances where such errors have occurred, and I shall set down the appropriately emended text, in accordance with duly emended and accurate texts on which I have based my own emendations.

Now it has been my intent that, after recording all the relevant statements, I shall be determining the halakhah and deciding between the various opinions, as this is the objective of the exercise, and to ensure that we shall have a single Torah and a single law. [ . . . ] And I have seen the Tosafot [a set of medieval glosses on the Talmud], books of Naḥmanides [Moses ben Naḥman (1194–1270)], of R. Solomon Ibn Adret [Rashba (1235–1310)], and of Rabbenu Nissim [of Girona, the Ran (1320–1376)] of blessed memory, replete with arguments and proofs; and who is there who would have the presumption to approach this forum to add further arguments and proofs thereto? And who is there who would have the presumption to place his own head between these mighty mountains to decide between them by means of arguments and proofs, either to contradict what they themselves did elucidate or to determine the halakhah in matters where they did not themselves decide? For on account of our many sins, the measure of our intellect has become too limited to comprehend their statements, and a fortiori to attempt to be cleverer than them; and moreover, even if it had been possible to proceed along this route, it would not have been fitting to appropriate it for ourselves, as it is an exceedingly lengthy route.

And accordingly, I have seen fit that since the three pillars of halakhic teaching upon which the House of Israel relies in their rulings—that is to say, R. Isaac Alfasi (1013–1103), Maimonides, and Rabbenu Asher [ben Yeḥiel, the Rosh (ca. 1250–1327)] of blessed memory, I considered that wherever two of these agree with one another, we shall decide the halakhah in accordance with their view, except where—in a few instances—either all the sages of Israel or the majority of them dissent from that view and a contrary practice has thus been established.

And wherever one of the three aforementioned pillars has not openly stated his view in regard to the law in question and the remaining two pillars are in dispute over the matter, we assuredly have Naḥmanides, Rashba, the Ran, the Mordechai [ben Hillel (1250–1298)], and the Sefer mitsvot gadol [Great Book of Commandments (1247), by Moses of Coucy], of blessed memory available to us; we shall go in whatever direction the wind [see Ezekiel 1:20], that is to say, the spirit of holy beings, is blowing; for we shall determine the halakhah in accordance with that view toward which the majority of them incline.

And in a case where not a single one of the three aforementioned pillars has openly stated his view, we shall decide the halakhah in accordance with the words of the sages of renown who have set out their view in regard to the law in question. And this route, the king’s highway, is the correct one and in accord with reason for the removal of any stumbling block.

Now if, in a few countries, they have established a prohibitory practice in regard to a few matters, notwithstanding that we shall have determined the halakhah as being to the contrary, let them maintain their practice, as they have already accepted the words of the sage who decreed the prohibition, and it is forbidden for them now to establish a permissive practice, as we find in b. Pesaḥim chapter four [51a].

And since the various sections of the indexes appended to the Turim are exceedingly brief, and a person wishing to look for one particular law will occasionally be unable to determine whether it is to be found in this section or in another section, or indeed whether the author of the work has incorporated that law at all, I have accordingly seen fit to create other indexes that list all the laws specifically appearing within the section in question. After that, I recorded the references to all the novel laws included by me in this explanatory work called Bet Yosef, so that anyone may find the particular law he wishes with ease.

And the practical benefit of this work is plain, and to those who choose this abridgment, it represents a route that is both long and short [see b. Eruvin 53b]. And as for one who lacks the strength to hold out, let him consult it so as to enable him to understand the meaning of the statements of the author of the Arba‘ah turim properly. Hence the present compilation contains within it nourishment for all, and hence I have called it Bet Yosef; for in the same way as all were provided with bodily nourishment from the house of Joseph [see Genesis 47:12–26], so likewise will they obtain spiritual nourishment from this work. And yet a further reason is that it represents my portion from all my labors, and it constitutes my house in this world and in the world to come. And I ask of the Almighty that He may assist me, for the sake of His glorious Name, in composing this work cleansed and polished so as to be free of all mistakes and errors. In Him has my heart placed trust and I have obtained assistance. May He have mercy upon me and favor me as a free gift; for to those unto whom He shows grace, they obtain grace, and to those unto whom He shows mercy, they obtain mercy, as it is written: And I will be gracious unto whom I will be gracious, and will show mercy unto whom I will show mercy (Exodus 33:19).

Credits

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 5.