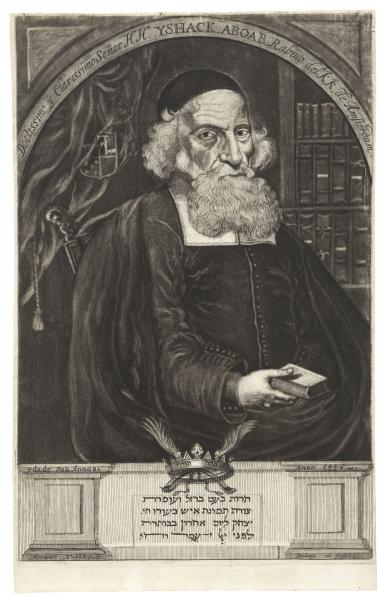

Nishmat ḥayim (Breath of Life)

Aernout Naghtegaal

Isaac Aboab da Fonseca

ca. 1636

We are therefore obliged to examine the words of the living God, which are expressed through the wonderful wise men who have received the truth [i.e., kabbalists], the foundation of the Torah. The first of these is the great rabbi, Naḥmanides, since we have seen that R. Abravanel cited his words in the Torah portion of Shalaḥ. His words seem to contradict each other; this is what he said:

The sixth opinion that I have seen concerning this matter is that of Naḥmanides in his commentary on the portion Aḥare mot, and he reinforced this opinion in his Sha‘ar ha-gemul. His opinion is that excision [karet] for all of those who are liable to this punishment is not equal, but rather that there are three types, etc.”1 Abravanel concluded by saying: “Behold, it has become clear that two rabbis, Maimonides and Naḥmanides, agree with the idea that excision for the soul refers to the corruption of the soul and its complete deficiency, and they agree regarding the excision for idolaters and those who curse God that it is an excision for both the body and for the soul.”2

He expressed his reservations with this opinion, but negated his view. And indeed, I investigated and browsed through his words, and behold, my hard work was rewarded. This is what Naḥmanides has to say:

Now we must interpret the great punishment, which is excision, and this is indeed the loss of the soul. Thus it is said in the Sifre: “Since it says often states karet and yet I do not know what this is, the verse therefore states: That soul will I make lost (Leviticus 23:30), which teaches that excision is nothing other than loss.”3 However, this loss is nothing other than punishment and sorrow; it does not mean that the evil man will die and his soul will be lost and will return like the soul of a beast and be negated; for the soul of a beast will return to its foundational element, which is air. And the foundational elements are like all of the other material objects that return to their elements and their dust, whether they are thin or whether they are thick; and nothing has been lost since the day that the world was created and until now. Rather, everything is transformed and returns to its foundational element, and this is true of all losses for the entire duration of the world.4

From these words which Moses spoke,5 it seems that the loss is not the corruption of the soul into the soul of beasts (as Abravanel wrote), since after this statement, further along in his exposition, he wrote as follows:

All the more so, this soul, which is supernal, cannot possibly be negated and lost, and it will not return to a bestial nature and join with the four foundational elements, which are from it. For this is not the truth according to the kabbalah, and there is a great distance from the truth to all that was rejected by the wise ones. If the soul were to return to its foundational element, as is the ultimate consequence of created things that are prone to generation and corruption, which all return to their foundational elements, it would be blissful and it would be good for it, for this would be the great reward and the honored prize. Nevertheless, this entire study is based on that which was mentioned above from the words of the sages,6 that those who require this punishment are sentenced to Gehenna for twelve months, as is fitting for them. After their sentence is finished, their souls are burned and are made into ashes, that is, their formation is negated from its previous status, like an object that is burned and turns to ashes. And the spirit of God, may He be blessed, which is the guiding spirit and the will, scatters them under the feet of the righteous, that is, it puts them at a level that is under that of the pleasure and rest of the righteous. This is a level that does not consist of punishment and sorrow, as at the beginning of their process, but neither does it have the delight of pleasure like the righteous, etc.7

At the end of his exposition, he wrote:

In regard to those who are severely and completely wicked, who are sentenced to punishment for many generations, it is the will of the Master, may He be blessed, to sustain them and to sentence those souls to a punishment and sorrow that does not destroy that sinning soul, as it is written [Isaiah 66:24]: For their worm shall not die, neither shall their fire be quenched. The same applies to the body: a person would prefer to suffer temporarily than to live a long life without conclusion or end to his suffering and sorrow.8

If it is so, then according to this approach, there is no negation or annihilation for the soul, contrary to the opinion of Abravanel concerning the matter. And if he thought that negation of the soul applies to middling people,9 then regarding his interpretation that they are made into ashes, that is, that “their formation is negated from its previous status, like an object that is burned and turns to ashes,” this is nevertheless not a complete negation. For they still exist, and Naḥmanides’ text answers Abarbanel, as it states that they are scattered “under the feet of the righteous.”

Notes

[Abravanel, Commentary on the Torah, Numbers, 15:22—Trans.]

[Ibid.—Trans.]

[Sifre, Emor 14:4—Trans.]

[Naḥmanides, Sha‘ar ha-gemul, p. 288—Trans.]

[See Deuteronomy 1:1; reference to Moses Naḥmanides.—Trans.]

[See b. Rosh Ha-shanah 17a—Trans.]

[Naḥmanides, Sha‘ar ha-gemul, p. 288—Trans.]

[Ibid.—Trans.]

[I.e., neither perfectly good nor completely evil.—Trans.]

Credits

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 5.