Consulta sobre o uso das pinturas (Inquiry into the Use of Paintings)

Moses Raphael d’Aguilar

17th Century

Since the law prohibits one, in no uncertain terms, from depicting figures, the question one may ask is how Jews have had all manner of paintings in their homes? And it is not enough to say that only cast and embossed figures should be prohibited rather than those that are painted and woven, because both types of images are liable to be a stumbling block leading to idolatry, and should, therefore, also be prohibited.

Replying to this misgiving as briefly as possible, since it is so important and timely, I first admonish that the evidence to resolve the aforesaid reservation must be pondered well, for it is succinct and brief, and it corroborates what has been customary and accepted over many centuries within Israel, the Lord’s assembly, who have indulged, in so many ways, in everything that may have the appearance of idolatry, as can be seen in the institutions that deal with this matter. And to proceed within clearly defined boundaries, I shall set down the distinctions of the case and shall then bring the proofs on which each section is predicated. And I state the following:

- Regarding images, there are three distinctions: the first is that every figure known by anyone to be an image of idolatry and veneration, an animal, plant, river, mountain, or any fashioned form, not made of natural material, is prohibited from being made or placed prominently in one’s home, whether it be painted, and recognized as a figure that is venerated, or made for such a purpose.

- The second is that all the images found in the sacred scripture wherein the prophets state that God or one of His angels appeared to them in spirit or prophetic vision. This would include a figure of human form whereby He appeared to Isaiah and Daniel; the four animals with four faces that appeared to Ezekiel, the winged seraphs that appeared to Isaiah, and similar instances. This section includes figures of any celestial object. It also comprises the figure of any object consecrated to God, such as the Temple or any of its vessels. Thus, this whole section consists of figures in which God or any of his ministers appear, as well as figures consecrated to Him. Although all these objects should not be made or used for idolatry or veneration, it is impossible to prohibit their being found in the home as in the case of the first mentioned figures. Nevertheless, they differ from the ones in the first category, in that the latter are not permitted to be of substantial size or painted, whereas the former are prohibited only if they are prominent or embossed, but are allowed if they are painted: except for certain types of objects of the same category that are also prohibited when painted, for the reason we shall state below.

- The third distinction consists of any images not belonging to either of the two previous categories, such as animals, fish, birds, trees, and any animals not venerated or made for such a purpose. All these may be brought into the home, whether they be painted or prominent, without compunction.

This is the decree of Israel, which proposition we shall be demonstrating through sacred scripture. We shall begin with the origin of this precept, which is stated in the Decalogue in these words. Thou shalt not make unto thee a graven imagen or any manner of likeness that is in the heavens above or that is in the earth below or that is in the water under the earth, etc. (Exodus 20:4). The apparent meaning of these words is that a curious person is obligated to ask the question, since it is apparent to him that they contain the prohibition of making any image whatsoever. However, the true meaning of these words is that this precept contains Divine will and design, and attempts only to highlight figures made for veneration and recognized as such, as is the present practice of non-Jewish people.

First, if this precept had been absolute, and these words were to be understood as referring generally to any type of figure, whether used for veneration or not, it would also be prohibited to make any image of a created object, without exception. [ . . . ]

Second, this can be proven by the number of commandments in the Decalogue, which sacred scripture holds to be ten, neither more nor less. [ . . . ]

Third, this can be proven by what scripture states. Thou shalt make thee no molten gods (Exodus 34:17). [ . . . ] Thus, if indeed the verse in the Decalogue were prohibiting any type of image, the verse prohibiting figures of idolatry would be superfluous. [ . . . ]

Fourth, this can be proven in the following manner. When it comes to commenting on the Law, the tradition cannot be contrary to what the Law expressly states; however, where the text is ambiguous and may tolerate a clause and condition that is not expressly stated, tradition can explain it by adding to such a clause and condition. [ . . . ]

Fifth, this can be proven from sacred scripture, by means of the verse that says: Cursed be the man that makes a graven or molten image, an abomination unto the Lord, the work of the hands of the craftsman, and all the people shall answer, Amen (Deuteronomy 27:15). And this is the proof: anything marked is to be distinguished from another; this verse speaks about a molten image that is an abomination to the Lord; thus, there is a molten image that is not an abomination to the Lord, and this is one that is not a figure of something venerated. [ . . . ]

Sixth, this can be proven by the practices and customs of ancient Israel, whereby this precept of prohibiting figures is understood as applying only to venerated things. [ . . . ]

And since the aforementioned reasons are true and compelling, I well know that, as they are delicate in nature, they require an articulated voice to corroborate them and explain with examples and declarations that cannot be done in writing, because much experience in the sacred scripture and the Hebrew language is required to ponder their power; however, I did what I could and may God instruct us always to be precise in matters pertaining to His holy service. Amen.

Translated by

.

Other works by de Aguilar: Epítome da grammática hebrayca (1660); Dinim de sehitá e bedicá (1681).

Credits

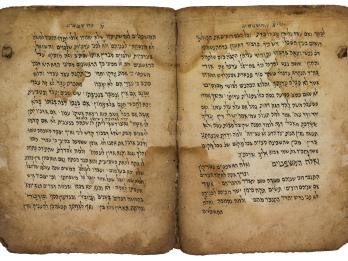

Moses Raphael d’Aguilar, Consulta sobre o uso das Pinturas (Inquiry into the Use of Paintings), Ms. Ets Hayyim (Amsterdam), 48 A 11, 196v–201v.

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 5.