Responsum: On the Prohibition of Teaching Karaites

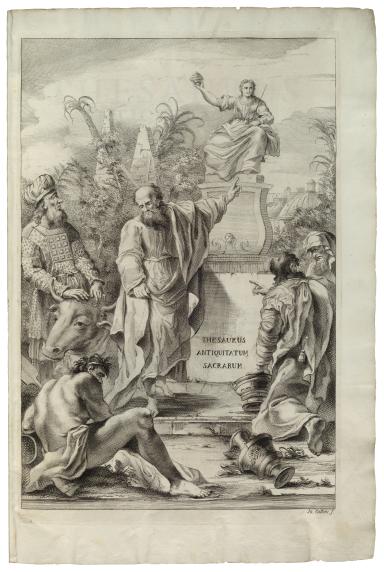

Blasio Ugolino

Giovanni Cattini

Elijah Mizraḥi

ca. 1500

57

On the ban pronounced at a gathering of some members of the community in the city of Constantinople, together with some town representatives, in the synagogue of the community of Constantinople. It was decided to enact the following ban, that one may not teach Karaites any topic of study, neither the Bible, nor the Mishnah, not the Talmud, nor halakhot, not aggadot, nor biblical commentaries that explain the plain meaning of the text, nor biblical commentaries that expound in the manner of the kabbalah, nor even any of the forms of science composed by Greek scholars, may their name be blotted out; not logic, nor physics, not metaphysics, nor arithmetic, not geometry, nor astronomy, neither musicology, nor musical intervals, nor any other theory of this type. One may not engage with them in the manner of teaching, not by posing questions, nor through argumentation, nor through studying by reading, and not even through studying by means of the composition of letters in the manner that children write them.

With this, they then sent and brought the leading rabbi of all these congregations, asking him to endorse the ban, but he refused to do so. He argued that it is improper to forbid a person from doing that which is permitted to him. And it is well known that these sciences are derived from the writings of the Greek scholars, which they based on their own ideas and on the fruits of their research. Anyone may teach such matters to gentiles, Muslims, Karaites, or to some other nation of their choosing, without violating any prohibition. How, then, can one declare a ban on such practices? When he observed that his opinion was not accepted, he declared an extension until the morning. However, those who were pushing for the ban realized that the rabbi was playing for time, and they therefore arose and pronounced the ban among themselves, declaring that they would come together in the morning to uphold their declaration, and that none of them would be permitted to retract, even if a majority wished to reverse their course.

When the teachers heard about this, they yelled at them, saying, “Why do you wish to forbid us that which has been permitted to us from the times of our fathers and forefathers to this day? For these sciences are based on books composed by Greek scholars, may their name be blotted out, and these works have been studied from when they were written to this very day. They have been passed on from one nation to another, from gentiles to Jews, from Jews to gentiles, from Muslims to Jews, from Jews to Muslims, from gentiles to Muslims, and from Muslims to other gentiles. Furthermore, more than a few great men in ancient times would teach Karaites, gentiles, and Muslims, in exchange for payment, so that they could earn their livelihood in an honest fashion, and so that they would not have to perform other types of labor. Nobody uttered any kind of complaint against them. Now, what is our trespass and what is our sin [see Genesis 31:36] that you have come upon us with the sword of this ban to interfere with our occupation when there is no violence on our hands [see Job 16:17]?”

Several of the teachers then arose and approached the leading rabbi of all these congregations, in the city of Constantinople, and complained to him about this matter. He responded as follows, “This is not a good thing that they wish to do, as they do not have the authority to render forbidden to anyone that which is permitted to him. Now, return to your tents (Deuteronomy 5:26), and I will continue at my measured place [see Genesis 33:14], in my efforts to persuade them to change their minds.” But while he was speaking with them, some of the people who were behind the ban showed up, as they had heard that the teachers had gone there to complain, and the two factions began arguing with each other until the shouts of recriminations grew extremely loud. Then those who backed the ban left the scene in a state of extreme anger and called upon all wicked and base men [see 1 Samuel 30:22] to come with sticks in hand to beat anyone who would object to the gathering in the synagogue of the community of Constantinople, where they had come together to institute this ban.

In the morning, the teachers came together in a very large gathering, comprised of members of the community, town representatives, and elders, in the synagogue of the community of “Zitun.” They called upon the leading rabbi to join them there and disavow the plot of the group that sought to impose the ban, and he indeed went there. However, as they began discussing the issue, messengers came from the other gathering to the rabbi, asking him, “Why don’t you come with us to the synagogue of the community of Constantinople, where the first gathering was held? Instead, you have gone to this synagogue!” The rabbi answered, “It is because I saw that you have been joined by vain and light fellows [see Judges 9:4], whose whole intention is to do evil, to uphold this dispute, and they seek to get their way by hook or by crook.” They pressured him greatly to go with them, but he refused.

The group then sent more messengers to him, saying, “If you agree to listen to these messengers and go with them, you will be treated well. However, if you do not do so, you should know that the entire gathering over there has already ordained and accepted [see Esther 9:27] upon itself the decision to appoint another rabbi in your stead, to rule over them and lead them.” When the rabbi heard this, he got up and went with them, followed by a few elders of Israel. But the taskmasters, with sticks in their hands, were standing at the entrance of the synagogue of the community of Constantinople, to find out who it was and where he was, [any man] who dared presume in his heart to [see Esther 7:5] oppose their words. They issued a general proclamation [see Exodus 36:6] that “if anyone who is estranged from our plan approaches [see Numbers 3:10] the entrance to the Tent of Meeting [i.e., the synagogue], where they have gathered together to uphold this ban [see Numbers 16:11], he shall be put to death.”

When the teachers heard this evil tiding [see Exodus 33:4], they stood, each man at the entrance to his tent [see Exodus 33:8], and could not approach the entrance to the Tent of Meeting [see Exodus 40:35] to speak and protect themselves. The rabbi observed that not one of the teachers was there, and that none of those gathered there wished to speak against this ban, as fear of the taskmasters had fallen upon them [cf. Esther 8:17]. For those gathered there had already pronounced the ban the day before and had declared that they would all unanimously agree to impose the ban and that not one of them was permitted to retract, even if he heard the most convincing proofs against their opinion, even if the majority wished to change their minds. The rabbi therefore remained silent and did not say anything, good or bad [see Genesis 31:24]. The people involved in the controversy [see Deuteronomy 19:17] with the teachers then stood up and ascended to the Sanctuary of the Lord and brought out Torah scrolls and pronounced the ban in loud voices, as they had planned to do [cf. Genesis 11:6].

In my humble opinion, this ban is in effect only for those who agreed to it, but it does not apply to anyone else. There are several reasons for this decision, which I will proceed to explain, with the help of God: [ . . . ]

And this is an a fortiori argument: in a case where one is liable to excommunication, if one was not excommunicated for the sake of heaven but for one’s own benefit, the excommunication is invalid. It therefore follows that in a case when one is not liable to any punishment—as in the situation at hand, where they wish to excommunicate anyone who violates their decree—if it turns out that they did not act for the sake of heaven but for their own benefit, whether to defeat their enemies or take revenge upon them, or for some similar purpose, it certainly follows logically that their ban or excommunication should be of no effect whatsoever to the rest of the world. This is true both according to the first and the second group of geonim.

Furthermore, in practice all people fail to observe this ban, even those who agreed to its imposition, as everyone asks and answers Karaites regarding any commandment over which there is any uncertainty. We have not heard that any resident of the city has refused to respond to a Karaite or to explain to him all that he needs. What is more, even when it comes to the teaching of Karaites, which is a regular interaction, the main individuals behind the ban, those who held the Torah scrolls in their hands, have themselves violated its terms. Since this is one of those cases where “the majority of the community is unable to abide by an enactment”—which is certainly true here, as none of them uphold it—it is obvious that this decree and ban are not in force at all. It is therefore proper to compel them to annul the ban, so that people will not keep violating it, as I have already clarified satisfactorily, and this applies both according to the first and the second group of geonim.

In addition, after this ban was enacted, several sages arrived from those who had been expelled from Spain—may the Rock protect and sustain them—and they teach Karaites in public. They know that the residents of the city do not have authority to impose this decree even on fellow residents if they object, and certainly not on those who were not living in their city, and together these are the clear majority. Nobody objects to the behavior of these sages, and thus the decree has been completely nullified. For this decree did not merit widespread observance, and thus everyone agrees that the ban is of no effect whatsoever, as the decree has been annulled. These men cannot have greater power than Daniel, may he rest in peace, or the students of Shammai and Hillel, as they decreed against the use of oil manufactured by gentiles, but when they examined and found that the decree had not become widespread in most of Israel, Rabbi Judah the Prince and his court arose and nullified it [m. Avodah Zarah 2:6]. This does not mean that they actively nullified it, as it lapsed of its own accord; rather, they simply publicized that it had become nullified. This is my humble opinion on the matter,

Elia Mizraḥi

Other works by Mizraḥi: She’elot u-teshuvot (1546); Mayim a’mukim (1647).

Credits

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 5.