She’elot u-teshuvot yeshanot (Old Responsa): On Marital Deception

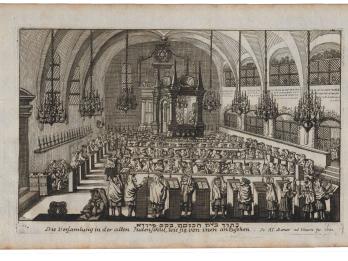

Johannes Alexander Böner

Joel Sirkes

First Half of the 17th Century

Question 99

Reuben has the following claim against his wife. He was informed about her that she had prepared for herself a concoction that would kill the child in her womb, which she had conceived through harlotry while he was overseas. He has several other ugly claims against her, of which he was informed when he returned from overseas. His wife responded that none of this ever occurred. The husband brought forward one witness who testified as follows in court.

Before the Passover festival, the woman approached me with a sickly face and said to me, “I fear that there is something wrong with my stomach, as the area around the chest is constantly pushing and pressing against me. What should I do?” I told her that she must present a urine sample, and I indeed examined her urine sample on the following day, by means of which I observed that her sinews and limbs were blocked. I then asked her if she has had a period and she replied in the negative.

The second witnesses testified in Yiddish:

I was living in her father’s house. There I saw her on several occasions engaging in loose behavior. He said, “One young man was clapping and dancing in the winter-house, and then I observed that young man holding this woman and kissing her. And a few times this young man came at night and kissed her, and sometimes he stole up to her room, and she got up and went down to him at night, they did this until her father went to lie down, and then they went down together.” He also testified that she would open a window for that man, so that he could sneak into her house. He also attested that he could hear them conversing in her room, up in the attic, with the door closed. He further testified that together she went with her mother several times to the house of the organ maker and sugar maker and they came home drunk from drinking wine and the woman praised these non-Jews, [and he testified further] that she gave him presents. He also testified that she had a drink made to bring on her period, and he said that he himself tasted the drink. And he testified that the Jewish woman who made that drink told him that the woman did not want to pay her for that drink. The Jewish woman also told him that she [i.e., the woman in question] went with her mother and with So-and-So to a witch to do something to her, but, God forbid, I did not want to do that same thing and go with them. This is all his testimony.

A third witness then testified:

I often went with that young man to So-and-So’s house, because he had a relative in his house, and drank with that woman and played dice and danced and saw this young man caressing and kissing that woman while dancing. And we asked him whether he saw that she was hugging and kissing him, and he responded, “I did not pay proper attention to it, I was playing on the board [some kind of gambling, board game].” This is all his testimony. He also testified: I saw that woman drinking nonkosher wine with the organist [organ maker] in the house of So-and-So. This is all his testimony.

Response

[ . . . ] It is certainly the case regarding the first witness, who testified that he examined her urine and discerned that her sinews and limbs were blocked, and that she admitted to him that she did not have a period, that this testimony is insufficient to give her the status of a pregnant woman. This reason is that it is likely that something happened to her body, which weakened her, and as a consequence she skipped her period, as this can typically happen to women. The husband cannot combine the various startling, ugly rumors, and claim that he believes them and thereby render his wife forbidden to him. As the Maharik1 has already written, this [that a husband can render his wife forbidden to him on the basis of the testimony of one witness] is possible only when one fully believes the witnesses and relies upon him, and he is certain that the witness is not lying. It does not apply when one believes the witness because he suspects his wife due to various suppositions and pretexts. It is further written by the Hagahot Maimoniyot2 in chapter 24 of Hilkhot ishut, in the name of R. Joseph, that nowadays, when R. Gershom’s enactment against divorcing a woman without her consent is in effect, we should ostracize someone who renders his wife forbidden to him by saying that he believes one witness as though he were two witnesses, for he effectively negates the enactment of R. Gershom by divorcing her without her consent.

In sum, this woman is permitted to her husband, and the court does not have the authority to force him to divorce her against her will. With that said, if the husband does not want to return to her, it is equally the case that we do not have the power to compel him to live with her. Rather, he must provide her with her sustenance and all the other terms of the marriage. If the husband contends that he wishes to divorce her and pay her the full sum of her marriage contract, whereas she does not want to get divorced, we cannot force her to do so. However, in such a situation, since she is the one who is objecting, he is not obligated to provide her with her sustenance. This is as stated at the beginning of Tractate Ketubbot [2b]: “If it is the women who postpone the marriage, why do they eat from his food, etc.?” If the wife wants a divorce, he must either give her the full sum of her marriage contract or live with her. If he wants to divorce her as well but claims that he should not have to pay her the marriage contract, nor does he wish to live with her, we proceed as follows. His savings are inspected and he pays what he can afford. He then takes an oath that he does not own anything more, and a debtor’s arrangement is made for him, which means that he must write a promissory note for the outstanding sum that he owes her. This is similar to the Rambam’s ruling concerning the case of a pauper who cannot afford to give to his wife the amount he owes her:3 he is compelled to divorce her, and the marriage contract is treated as a debt until he finds the means to pay it.

I have hereby written my opinion on the matter; I, Joel, the small and youthful, son of my beloved father, our honorable teacher and rabbi, Samuel, may his memory be for the life of the world to come.

Notes

[Joseph Colon Trabotto (1420–1480, Italy), a renowned Talmudist.—Trans.]

[Meir ha-Kohen of Rothenburg (ca. 1260–1298).—Trans.]

[In Sefer nashim (Book of Women) of Maimonides’s Mishneh Torah, note 10.—Trans.]

Credits

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 5.