Memoirs of the Life of Daniel Mendoza

Daniel Mendoza

1816

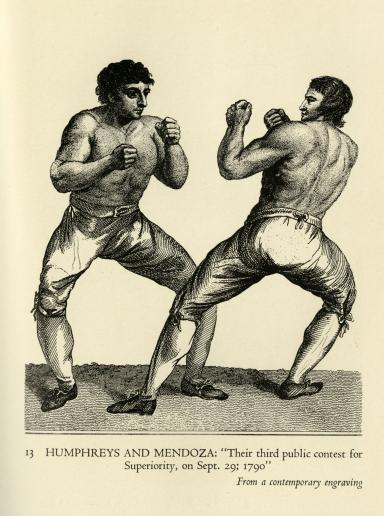

Few events of a similar kind ever attracted the attention of the public, in such a degree, as the contests between

Mr. Humphreys and myself

. The long correspondence which passed between us previous to our second contest, the skill which, as was candidly acknowledged by the friends of both parties, was mutually displayed; these and various other circumstances contributed to excite, in an extraordinary manner, the attention not only of spotting men, but of all ranks and descriptions of persons, generally; and I found, on my return to London, that our contests were the general subject of conversation all over the town. I had even the almost unprecedented honour of being frequently alluded to and mentioned in many dramatic performances; for instance, The Duenna, The Farmer, The Road to Ruin and others.

Many of my friends who had been rallied for their want of judgment in supporting me in the first contest with Mr. Humphreys, had now a fair opportunity of retorting, which they did not fail to avail themselves of. Several songs were made on the subject of the late victory; among others, the following was sung with great applause at several convivial meetings.

Song

Humphreys and Mendoza

Credits

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 6.