Neḥmad ve-na‘im (Nice and Pleasant)

David Ganz

David Ganz

Beginning of the 17th Century

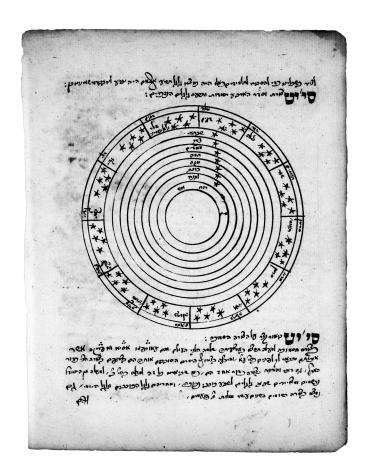

Nicolaus Copernicus, from [Polish] Prussia, was a great man, who was more proficient in the field of astronomy than all the wise men of his age. Indeed, all the wise men of our time unanimously attest to the sharpness of his intellect and the profundity of his grasp of this field of wisdom. It has been said about him that from the days of Ptolemy there has not been found a man like this in any generation with regard to the depths of his wisdom. In his great acuity of mind, he set out to prove that planet earth is continuously undergoing a revolving movement. Now this is not a new idea, as it also occurred to the ancient ones thousands of years ago. For I have found in the work Ha-shamayim ve-ha-‘olam [Aristotle, De caelo et mundo], book II, part 4, that this was indeed the opinion of the outstanding scholar Pythagoras and his followers. The wise Copernicus wrote a wonderful book on this topic, a work of exceedingly great profundity, and he completed this exceptional volume in 1500 CE, which is the year 5258 [sic] to the creation. This scholar died in the land of his birth, [Polish] Prussia, in 1543, the year 5305 [sic] to the creation.

Now, O reader, even though you might imagine, based on all that was related above, that the fundamentals of the wisdom of astronomy came to us from the gentile nations, you must know that this is incorrect. For in fact the main knowledge of this wisdom first emerged from our own people. This was written by the rabbi [Maimonides] in the Guide [of the Perplexed] I.71; [Meir Gabbai] in Derekh emunah wrote likewise in section III, and it is cited by [Azariah de’ Rossi’s] book Me’or ‘enayim in chapter 2, and also in chapter 40: “astronomy was initially from Israel, but when the nations gained control of us they came into possession of this wisdom. Since we are learning from them, it appears as though they were the originators and that it emerged from them, whereas in fact the reverse is the case.” For who is greater than Solomon, as there was no man as wise before him, and none like him arose afterwards, and we have already shown above how he glorified himself in his knowledge of astronomy. However, we have not seen his works or the writings of the other ancient sages on astronomy. Maimonides, of blessed memory, states likewise in chapter 17 of [Mishneh Torah,] Laws of the Sanctification of the New Month [17.24], that the books on astronomy written by King Solomon, may he rest in peace, or by scholars of Israel “from the tribe of Issachar, have not been transmitted to us.” It is possible that those volumes came into the possession of the gentile scholars, and they pride themselves in this knowledge as though they discovered it all on their own with their own intellects. The author of Shevile emunah [Meir Aldabi, 14th c.] formulates a somewhat similar idea in section eight.

You should thus know that from the day of our exile from our land onto foreign soil, in the great expanse of our exile, the nation of God has been scattered and dispersed among the peoples (Esther 3:8), in the four corners of the world, and we have suffered one breach after another and have been tossed from one nation to the next, and from this kingdom to that people. On account of the many troubles that have encompassed us, we are all like lost sheep; we have been wholly consumed [see Psalms 73:19]; the cunning charmer and the skillful enchanter [see Isaiah 3:3] have decreased, and the noble wisdoms have dwindled away from us, until virtually all memory of them has become lost [see Psalms 9:7]. Occasionally there can be found, one from a city and two from a family (Jeremiah 3:14) who know something of this wisdom. The limited books in our possession in these times, which deal with matters of astronomy, are based on books by gentiles; they learned from the gentiles and received the traditions from them, as Maimonides and other authors themselves admit in their works. Indeed, they provide only a few, slender notes on the books of the ancients, and even though they include in their works almost all the wisdom of astronomy, nevertheless, it is merely gleanings and leftovers from Ptolemy’s Almagest and other works on astronomy.

Consequently, even if we learn some fine and novel ideas in the field of astronomy from them and their books, this should not be considered of no value to us, and there is nothing wrong with this at all. For we have already found in [b. Shabbat] chapter nine, regarding the laws of garden beds,1 that the sages themselves accepted from the Amorites the natural laws of how plants draw sustenance, as the sages said that they [the Amorites] were experts in the planting of olive trees, vines, and fig trees, and that they were called Horites [ḥori; Genesis 36:20] because they would smell [heriḥu] the soil,2 or because they would taste the earth like a snake [ḥivya];3 see Rashi’s commentary ad loc [85a]. They also said in the second chapter of Tractate Megillah that whoever says something wise, even if he is from the nations of the world, is called wise, as it is written: and [his] wise men said to him (Esther 6:13). The sages also instituted that upon seeing such individuals one should recite the blessing, “who has given of His wisdom to flesh and blood,” as stated in [b. Berakhot] chapter nine [58a], and cited by the Tur in Oraḥ ḥayim, § 227. Who is greater than our master Moses [Maimonides], and he wrote as follows at the end of chapter 17 of Laws of the Sanctification of the New Month: “since all these matters can be demonstrated by clear, flawless proofs, leaving no room for anyone to question them, we have no concern about the identity of the author, whether he is a prophet or an idolater. For regarding anything whose reason has been discovered and been shown to be correct through rigorous proofs, we rely on the individual who issued these statements or taught those concepts, on the proofs he presented and the reasons he made known.”

Notes

[I.e., the prohibition against planting a mixture of diverse species in the same garden bed; see Deuteronomy 22:9.—Trans.]

[To determine which plants are fit to grow there.—Trans.]

[And therefore they were also called Hivites (ḥivi; Genesis 36:2).—Trans.]

Credits

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 5.