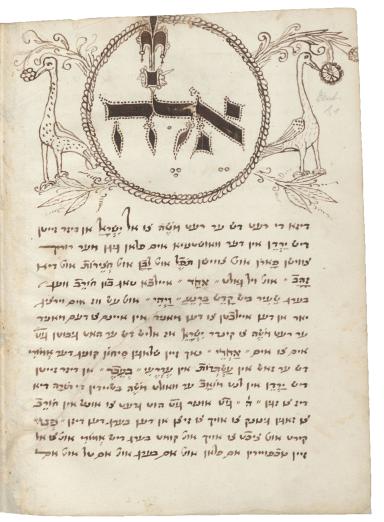

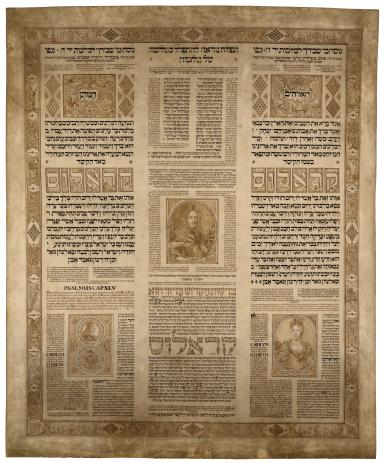

Spanish Translation of the Bible

Yom Tob Athias

Abraham Usque

1553

In his De officiis, most discreet reader, Tullius Cicero writes that nothing can move us so powerfully as to see some form or kind of benefit, which must be esteemed all the more, the less it is of an individual nature, because everyone searches for what benefits himself and very few seek the common good. For this reason, hoping to satisfy my desire, which has always favored universal benefit, even though some may say my own, and from whose tongues I do not seek to defend myself since I hold that they do not offend me, I have had the Bible translated into our Spanish so the other nations do not complain that their native sons have been deprived of this benefit. For Italy, France, Flanders, Germany, and England do not lack it, and even in Catalonia, in our Spain, it has been translated and printed in the Catalan language itself.

And since in all the provinces of Europe or in most of them the Spanish tongue is the most prevalent and the most prized, I have sought to make this Bible of ours—as it is in the Castilian language—as the closest to the Hebrew truth as possible, as the fount and source from which all drew, by following as far as possible the translation of Pagnino and his Thesaurus of the Sacred Tongue, it being word for word, corresponding to the Hebrew letter and so accepted and esteemed in the Roman Curia, even though this Curia was not lacking all the ancient and modern translations, and where Hebrew works were concerned, the oldest that could be found at hand; and also to this end I constantly sought out very wise and experienced scholars in both the Hebrew and Latin tongues. And although to some its language may appear to be foreign and uncouth, and very different from the elegant tongue which is current in our day, it could not be done otherwise, since wishing to follow word for word and not to express one word by two, which is very difficult, nor to put one before or after the other, it was necessary to follow the language which the Jewish Spaniards used long ago, which, although it is somewhat strange, if they consider well they will find that it possesses the uniqueness of the Hebrew diction and the gravity which the antiquity usually possesses. And, moreover, if the truth be told, just as all languages possess their style and phrasing, it cannot be denied that the Hebrew tongue has its own, which is that which shall be seen in this translation, which was not abandoned for another so as not to deprive each of that which is its own.

And let no one think that the reading of it is like that of the other books, which after once or twice are understood, because, as the sages say, each text has to be read ten times first before one can say that it has been read. “That it has been read,” it says, and not “that it has been understood.” How much more so with regard to sacred scripture where one who would be wise must take great care over it in order to penetrate something of the most elevated maxims and hidden mysteries that are contained in it, which very few or almost nobody will be able to access, since scripture possesses so few words, many maxims, and very sweet and beneficial teachings; and it thus corresponds to what the Lord says by the mouth of Joshua in Chapter 1 [verse 8]: Do not remove this book of the law from your mouth, and read in it day and night so that you shall keep and do all that is written in it, so that then your way shall prosper and then you shall understand. Each should read it for the purpose that he wishes, for the words of the Lord never did him harm. Moreover, I feel certain, if I may truly say so, regarding the confusion that diverse opinions can sow, since the work cannot have any defect in it, and those of the translation are not such that the discreet shall condemn them in any way since, as I have already said, the phrasing is that of the original language and the Ladino translations are so old and sententious, and among the Hebrews have become second nature.1 Therefore, some who consider themselves to be genteel wished to trouble and turn back this beneficial work, saying: they will sound poorly in the ears of the courtiers and keen minds; but, estimating such persons to be malevolent and disparaging people, I have nonetheless published it, always submitting the errors and faults to the correction of those who know best.

And it should be noted that in the places where one sees this star *, it is a sign that there is doubt about the sense of the word and sometimes diverse opinions—and although these have the same aim, [the translations] have always sought to follow the opinion that best suited the literal meaning and was closest to our language—and I hope they will jointly appear in publication with the Apocrypha, which are not in the Jewish canon, feeling as I do that this labor of mine is pleasing. And where the reader will find these half circles (), they will denote that what is inside them is outside of the Hebrew text but is nonetheless brought by the scholars for the clarification of the sense. And he will also find an .A. with two dots, which is the sign of the Tetragrammaton, the sacred name of the Lord.

Notes

[As used here, Ladino translations means Jewish calque translations of religious texts from Hebrew into Spanish (and later, into Judeo-Spanish). According to the author, although many Spanish-language readers would have found such imitative, word-for-word translations awkward, it was an approach that Sephardic Jews were used to.—Ed.]

Credits

Yom Tov Athias, ed., Biblia en Lengua Española: traduzida palabra por palabra dela verdad Hebrayca por muy excelentes letrados vista y examinada por el officio dela Inquisicion, trans. Abraham Usque (Ferrara: A costa y despesa de Yom Tob Atias, 1553). Republished as: Moshe Lazar, ed., Biblia de Ferrara (Madrid: Fundación José Antonio de Castro, 1996), pp. 5–6 (Al letor).

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 5.