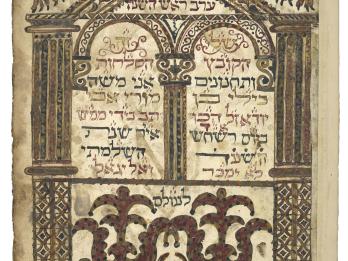

Takkanot Kandia (Regulations of Candia): On Purim

Moses Bili ben Judah

The Jewish Community of Crete

1545

May salvation be near, and we be cleansed of great sin. Amen.

I, the undersigned, have witnessed the bad custom practiced among young men on the days of Purim, that in the synagogue during the reading of the Megilah [Scroll of Esther] they throw rocchetta [fiery torches] and scoppietta [rockets]. They frighten the prayer leader, surround him, and pursue him with flames of fire, so that most times he stops the reading, and sometimes he runs away from the podium, scared that they might burn his clothes or his face. Furthermore, the entire congregation gets up, each person from his place, running here and there, out of fear of the torches and the fire, skipping and jumping from one place to another, like a fire in thorns. This causes great confusion and commotion in the synagogue, so that no one hears and understands the reading of the Megilah, which is the opposite of the ruling of the rabbis, of blessed memory, that one who reads the Megilah without the proper intent has not fulfilled his obligation. It is also the reverse of what they have said, regarding who hears the sound of a ram’s horn or the reading of the Megilah, that if he directs his heart, he has fulfilled the obligation and if not, he has not fulfilled his duty. What is even worse is that most of the congregation completely flees the synagogue in fear of these torches of fire, and they abandon the reading of the Megilah, concerning which the rabbis of blessed memory imposed several precise laws, e.g., that it must be read in [a quorum of] ten [men]. Even for those who ruled in accordance with Rav that a person who reads the Megilah at the proper time may do so individually, this ruling applies when he is forced to do so. However, whenever it can be read in a community all agree that this is preferable, and that is the best manner of performing the commandment.

In fact, one must be even particular in this regard, as we learned: priests at their Temple service and Levites on their platform and Israelites at their watches all ceased their worship and came to hear the reading of the Megilah [b. Megillah 3a]. Tosafot [a set of medieval glosses on the Talmud] raise a difficulty against this teaching by suggesting that they should finish their worship and then read the Megilah immediately afterward by themselves. Tosafot answer that it is better to read it with the community, because in this manner the miracle is publicized (the citation ends here). Indeed, it is clear from here that even though the priests at their Temple service and Levites on their platform and Israelites at their watches often consist of the required quorum of ten, in which case all agree that they fulfill the obligation of reading, and by the letter of the law they do not have to cease their service, nevertheless, the rabbis permitted them to suspend their service so that there would be more people at the reading, because in the multitude of people is the king’s honor (Proverbs 14:28). All the more so in the case at hand, as anyone who leaves the synagogue, even if he were to read the Megilah in his home he would only do so privately, which is not the correct manner. In addition, there are those who are lazy or who forget and thus do not even read it in their homes as individuals, while others do not know how to read it, and therefore they do not hear the reading at all. Consequently, this practice leads to a multitude of transgressions.

Even though it appears that these young men act this way because of the joy of Purim, this is truly a good deed that comes about by means of a transgression, and a custom that is like that is its opposite: hell1—he who is abhorred of the Lord shall fall therein (Proverbs 22:14). There is also an element of danger here, and “danger is more severe [than a prohibition,” b. Ḥullin 10a]. This is especially the case as gentiles come along with the Jewish lads, and their intention is evil and not good, and they throw the scoppietta with them, aiming it at people like archers, in order to strike a Jew.

Therefore I am zealous for my God, and I am furious at the young men who are accustomed to act in this way, and therefore I saw fit to do away with this bad custom from among us. To this end, I gathered the congregation, may its light shine, in the priests’ synagogue, and with the agreement of the honorable community head and his advisors, may the Rock preserve them, I stood and I declared—in the presence of a Torah scroll and the sounding of the shofar—that no person, small or great, should be permitted here to practice this bad custom in our community, i.e., the throwing of scoppietta and rocchetta in any synagogue of the four synagogues of our community, may the Rock preserve it. This may not be done on the evening of Purim or on its day, although outdoors and in the markets each person may do what is right in his eyes because of the joy of Purim. Whoever violates my statement will be called one who breaks through a fence (Ecclesiastes 10:8); the Lord will not be willing to pardon him (Deuteronomy 29:19). May all decent Jews be blessed by the supreme God, Creator of heaven and earth, Amen.

This occurred on the Fast of Esther in the year 5305 [March 8, 1545] in the time of the honorable community head, the honorable rabbi Yodlin Delmedigo, may the Rock preserve him. May great redemption come, Amen selah.

The words of the small and humble Elijah Capsali, the young son of my father and teacher, the sage R. Elkanah, may his light shine.

Notes

[This is a play on words: minhag (custom) has the same letters as gehinom (hell).—Trans.]

Credits

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 5.