Class 1: Rabbinic Authority after the Fall of the Temple

The rabbis redefined authority after the Temple’s fall, shifting it from priests to Jewish law, debate, and interpretation.

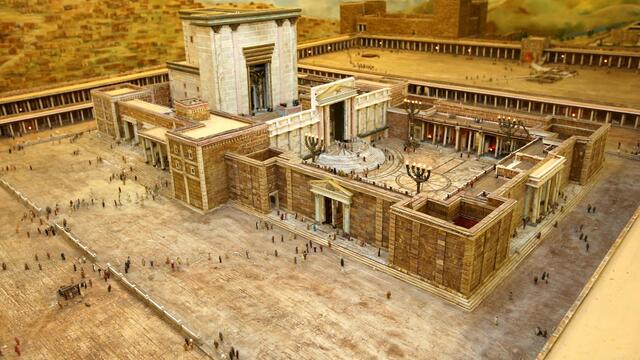

The Destruction of the Jerusalem Temple

In 70 CE, the Jerusalem Temple was destroyed. For Jews, this signified more than the loss of a building—it meant the loss of the center of worship, sacrifice, and priestly authority. The Temple had been God’s dwelling place, where priests mediated between heaven and earth through offerings and rituals. Without it, the system collapsed. How could Judaism continue without sacrifice, pilgrimage, and priestly leadership?

In the aftermath of any major change or upheaval, familiar supports and routines disappear amid enormous loss. But there are also new opportunities. Ancient Jews faced the challenge of rebuilding Jewish life—and their relationship with God—without the Temple. The rabbis represent one group that responded to this upheaval, creating new traditions that balanced continuity with the world of the Temple and practices that fit a Temple-less reality.

Torah Reimagined: From Biblical Scripture to Oral Tradition

The rabbis redefined the very idea of Torah as the foundation of authority. Torah refers to the first five books of the Hebrew Bible. But for the rabbis, Torah became a multilayered concept that included not only scripture but also oral traditions and ongoing interpretation. In their view, there were now two Torahs: the Written Torah of scripture and the Oral Torah passed through generations of sages. Mastery of this interpretive process—rather than priestly descent—became the basis of authority. Mishnah Avot 1:1 captures this claim with a chain of transmission that establishes the rabbis as the heirs to Moses and God’s revelation at Mount Sinai.

Authority through Interpretation and Debate

Other texts acknowledge that the world had changed. Tosefta Sotah 15:11–12 confronts the absence of sacrifice and reimagines practices of mourning. In the Babylonian Talmud, Megillah 29a relocates God’s presence from the destroyed Temple to the synagogue. Mishnah Horayot 3:8 overturns old hierarchies, placing sages (i.e., the rabbis) above priests. Mishnah Avot 5:22 and Mishnah Ḥagigah 1:8 elevate study itself as a sacred act, even when discussing aspects of Jewish law that are only loosely tied to scripture, “like mountains hanging on a hair.” Rabbinic authority both maintains continuity with older traditions and introduces bold innovation.

Women and Learning: The Case of Beruriah

While the normative model of rabbinic authority is male, the Talmud also hints at challenges to this model. In b. Eruvin 53b–54a, the sage Beruriah, the wife of Rabbi Meir, is portrayed as extraordinarily learned, correcting and instructing rabbis in their study. Though such figures are rarely written about, they suggest that rabbinic culture—though male-dominated—recognized the possibility of women being authorities in Torah and celebrated them. Beruriah’s presence complicates the picture of rabbinic authority, reminding us that the structures the rabbis built were not as monolithic as they first appear.

“It Is Not in Heaven”: Human Authority in Rabbinic Thought

The story of the Oven of Akhnai (b. Bava Metzia 59b) dramatizes one of the rabbis’ boldest claims. In a heated dispute, one rabbi calls on miracles and even on a heavenly voice to prove his point. Yet the sages reject divine intervention and declare, “It is not in heaven,” signifying that the authority to decide on a correct practice or interpretation belongs in their view not to God in the heavens but to human interpreters who engage God’s Torah through debate. God’s will is found not only in revelation but also amid the community of its interpreters.

The Paradox of Continuity and Innovation

Together, these sources show how rabbinic authority rests on a paradox. On the one hand, it is rooted in continuity with the past—maintaining an unbroken chain from Sinai, fidelity to scripture, and the sanctity of study. On the other hand, it is exercised through bold acts of innovation: redefining sacred space, reordering hierarchies, privileging debate, and even making room for exceptional figures like Beruriah. These texts reveal a tradition in which authority is not static but dynamic, reverence for tradition coexists with interpretive creativity, and disagreement is sacred.

Identifying and Reading Rabbinic Texts

The classical rabbinic texts—Mishnah, Tosefta, Palestinian and Babylonian Talmuds, and midrash—each follow different citation systems. The Posen Library follows scholarly conventions for how we cite these texts. The Mishnah, Tosefta, and Talmuds are organized by tractate, preceded by an initial designating which corpus they belong to: Mishnah (m.), Tosefta (t.), Palestinian Talmud (y., for the Hebrew Yerushalmi, meaning “Jerusalemite”), and Babylonian Talmud (b.). Mishnah and Tosefta titles are followed by two numbers designating the chapter and the mishnah or paragraph number within the chapter (e.g., m. Berakhot 1:1; t. Berakhot 1:1). The Babylonian Talmud is cited by folio (page) number, with the letter a or b to indicate the side of the page on which the text appears (e.g., b. Berakhot 1a or b. Berakhot 1b). The Palestinian Talmud combines these systems, organizing texts by chapter and halakhah (legal ruling or principle) followed by a number and letter designating the folio (e.g., y. Berakhot 1:5, 3d).

Discussion Questions

How did the destruction of the Temple shift the basis of Jewish authority from priests to rabbis?

What does the idea of two Torahs—one written and one oral—tell us about how the rabbis grounded their authority?

Why might debate and disagreement (e.g., as illustrated through the Oven of Akhnai) be seen as central to rabbinic authority?

What does Beruriah’s role in the Talmud suggest about gender and the limits of rabbinic authority?