The Origins of Rabbinic Judaism

The rabbis of late antiquity shaped Judaism through debates in the Mishnah, Talmud, and midrash, balancing continuity, change, and authority.

Who Were the Rabbis of Late Antiquity?

Who were “the rabbis,” and why do they matter? The rabbis of late antiquity were Jewish teachers and interpreters of scripture who lived in the centuries after the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple in 70 CE. They are not the same as a rabbi you might encounter in a modern synagogue, nor were they the only voices in Jewish life. But through the texts they produced—especially the Mishnah, Talmud, and midrash—they profoundly shaped the development of Judaism.

Rabbinic Judaism emerged in Roman Palestine and Sasanian Babylonia between 70 and 600 CE, as the rabbis claimed authority and engaged with Jewish traditions and surrounding cultures. The questions that the study of early rabbinic Judaism raises extend far beyond Judaism: How do religious traditions adapt to change? How do they balance continuity and change? How is authority in matters of scripture and practice established, challenged, and reshaped?

The Crisis of the Temple’s Destruction

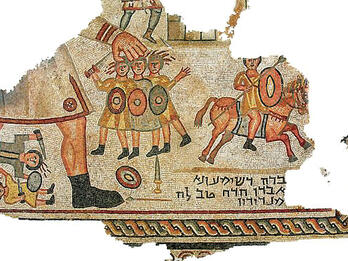

At the heart of this story is the rabbis’ adaptation to a dramatic change in Jewish history: the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple in 70 CE by the Romans. Until its destruction, the Temple was the central institution of ancient Jewish worship, where priests offered sacrifices to God on behalf of the people. The loss of the Temple and its sacrificial cult created a crisis of religious practice and authority. The rabbinic project—to preserve continuity with the past while reimagining Jewish life for the future—was one response to this historical trauma. The rabbis sought to situate their authority in a chain of tradition reaching back hundreds of years to the time of the Hebrew Bible, as they established themselves as interpreters of scripture, law, and daily practice. Though the rabbis were not the only Jews of their time, their response to the new reality would form the basis of Judaism.

Genres of Rabbinic Literature

Rabbinic debate and literature developed in multiple ways, resulting in diverse genres and collections. The Mishnah and Tosefta (ca. 200 CE) collect teachings organized by topic, while midrashic texts expand and interpret biblical material. The Babylonian and Palestinian Talmuds (ca. 400–500 CE) compile extended debates that reveal rabbinic reasoning in action. These texts layer traditions, preserve disagreements, and invite interpretation. Neither uniform nor literalist, rabbinic writings surprise readers by reshaping biblical verses in creative and unexpected ways.

Authority, Continuity, and Change

Authority is a central theme across the rabbinic works collected here. The first class that we present considers how the rabbis established their authority through claims of continuity with earlier generations and the Hebrew Bible. We will see how traditions claim legitimacy, how new voices enter ancient conversations, and how authority over sacred texts is negotiated in every generation.

The Rabbis and the Wider Roman and Sasanian World

The second class explores the world in which the rabbis lived, which was not only Jewish. They lived under Roman and Sasanian rule, and rabbinic texts reflect their awareness of imperial politics, urban cultures, and neighboring traditions, including Christianity. The class examines how rabbinic Judaism emerged within this wider late-antique context, asking how Jewish identities were maintained, adapted, and distinguished. The sources emphasize both assimilation and distinctly Jewish customs and routines, as the rabbis redefined practices ranging from dietary laws to communal worship.

The Enduring Legacy of Rabbinic Judaism

The third class turns to the legacy of the rabbis. By canonizing debate itself, the rabbis created a Judaism that could adapt itself across time and place. They interpreted scripture in striking ways, reflected on commandments (mitzvot) as ongoing obligations, and debated whose interpretations should prevail. The fourth class considers how rabbinic concepts and practices shaped Jewish religious life and how the methods of rabbinic interpretation resonate in the study of religion more broadly.

Gender, Power, and Interpretation

Gender is another important consideration in the study of rabbinic literature. Rabbinic literature was written by men and reflects a male-dominated culture, but it also contains interpretations of texts about creation, family, and community that invite questions about gender and power to help students see the rabbis in the ancient world and in ours.

This module introduces the basics of rabbinic Judaism and provides tools to think about religion more broadly: about continuity and change, the role of scripture, the making of authority, and the dynamics of gender and culture. Rabbinic literature is an ancient tradition but it continues to speak to the perennial challenges of religious life.

Learning Objectives

Identify and describe the major genres of classical rabbinic literature.

Analyze the ways rabbinic texts engage with earlier traditions and the reality of their historical context.

Interpret selected rabbinic passages using historical and literary methods.

Evaluate the lasting impact of rabbinic concepts and practices on Jewish religious life.