Minhage Vormeiza (Customs of Worms): On Weddings

Marriages on Weekdays

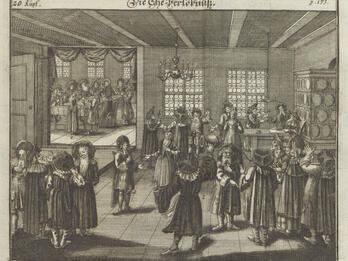

On Tuesday afternoon prayers, when the cantor reaches Taḥanun [prayers of supplication], the groom walks to the door of the synagogue while the congregation recites Taḥanun, and afterward the groom returns to the synagogue, and they recite evening prayers. The next day, Wednesday, at dawn, they knock on doors to summon people to the synagogue, at which point the beadle calls people to the mayn1 if the bride is a virgin. Next, the rabbi comes with the rest of the people, and they lead the groom from his home to the wedding house, which is called in the language of Ashkenaz [Yiddish] broid hoiz [bridal house]. The groom walks in front of the rabbi, followed by the rabbi, and after them all the people with torches and with musical instruments. However, the groom’s hood is stuffed into his collar [as a sign of mourning for the Temple]. The rabbi then takes the groom by the hand and leads him up to the platform beneath the wedding house, where he sits and waits. After that, the women come, likewise leading the bride from her home to the entrance of the wedding house, also with torches and musical instruments, and they stand there with her at the entrance of the wedding house.

Now the rabbi goes and leads the groom with his hand from the platform to greet the bride, to the entrance of the wedding house, toward the bride. The groom takes the bride by the hand, and the rabbi takes the groom by the hand, and he leads the bride and groom together to the platform. Two women accompany her to the platform, and while they are leading them to the platform the people throw wheat at the heads of the bride and groom, saying, “Be fruitful and multiply like this wheat.” They sit there together for a little while on the stage, the bride and the groom, and then the young men come and take the groom and lead him through a little entrance to the synagogue, which is in the south wall. There they seat the groom in the synagogue in the special place for grooms, on the northeastern side, which is on the right side of the holy ark. Meanwhile, the women lead the bride to her house. They light twelve wax candles in front of the groom, corresponding to the twelve tribes, and the groom sits in his place in the synagogue, but he does not pray until the cantor begins the Amidah out loud, at which point the groom stands and wraps himself in his prayer shawl, and he continues standing while the cantor recites the Kedushah. Immediately after Kedushah he sits in his place, and he does not put on tefillin, and he does not recite the Amidah. The congregation does not recite the supplication, nor “To the Chief Musician” (Psalm 20) or other special passages, and they finish the prayers.

The custom is to proceed as follows. At the time of the wedding, the rabbi comes to the groom’s house, and the groom goes with his hood stuffed into his collar as in the morning, walking before the rabbi, and all the people follow them with musical instruments to the wedding house. The rabbi seats the groom on the platform beneath the wedding house, and the relatives are also wearing their Sabbath finery. Afterward, the women also lead the bride with musicians to the wedding house up to the entrance of the wedding house, where she waits. Next, the rabbi comes and grasps hold of the bride by her clothing and leads her and places her to the right of the groom, with their backs to the north, while they face the south. The mothers of the groom and the bride walk and stand next to her during the blessings, and they take the tsippel2 from the groom’s hood and place it over bride’s head as a canopy.

The rabbi recites the betrothal blessings, with his face toward the east. After the betrothal blessings, the beadle takes the goblet from the rabbi’s hand and gives it to the groom to drink. Next, the mother of the bride takes it, and she also gives it to the bride to drink. The beadle calls two regular people to serve as witnesses, and the rabbi shows them the wedding ring and says to them, “Do you see that it is worth a perutah?”3 and they say, “Yes.” He then says to the witnesses, “Watch that he betroths her and also that he properly says, ‘You are hereby betrothed to me with this ring according to the religion of Moses and Israel.’” The groom places the ring on her finger, the one next to the thumb, while saying the phrase “to me.”

The beadle calls two other witnesses to testify regarding the marriage contract and the marriage terms, and the parties—including the groom—perform an act of acquisition for the marriage contract and the terms and the other documents, and after that they complete the blessings. When they have finished the blessings, the beadle gives the groom [wine] to drink, and the bride too, and then he places the cup in the groom’s hand, and the latter throws the cup at the wall, toward the lion’s head that is in the eastern wall. Immediately, they rush the groom joyfully and usher him into the wedding house before the bride, where they eat an egg and a chicken together. They also recite the seven wedding blessings there, and afterward they place the bride and groom alone in a room, where they eat. Only one woman is present there, one of their relatives, in order to serve them.

Notes

[A traditional wedding custom, which involved marching with torches to the synagogue courtyard.—Trans.]

[A long strip of fabric.—Trans.]

[The minimal value for a wedding ring.—Trans.]

Credits

Judah Leyb Kirchheim, “Minhage Vormeiza (Customs of Worms): On Weddings” (manuscript, Worms, ca. 1631). Published as: Juda Löw Kirchheim, Minhagot Vermaiza: Minhagim vve-hanhagot (Customs of Worms Jewry), ed. Yisra’el Mordekhai Peles (Jerusalem: Mif‛al torat ḥakhme Ashkenaz, Mekhon Yerushalayim, 1987), pp. 76–82.

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 5.