Postwar Jewish Life Writing

Life writing in the postwar period explored the Holocaust, displacement and migration, cultural identity, and the deteriorating situation of Jews behind the Iron Curtain.

Postwar life writing in Europe and the United States explored many important themes: the Holocaust, cultural displacement, the need to define place and memory, a renewed awareness of the importance of family, and the exploration and celebration of the diverse journeys that lead from poverty and obscurity to fame and recognition. Many of those who made those journeys did not forget their Jewish context. Their life writings revealed a lingering amazement about how they could reinvent themselves even as they took memories of their old culture with them.

Life Writing on the Holocaust

Interest in life writing about the Holocaust depended greatly on language and place. While memoir literature and historical research flourished in Yiddish in the immediate postwar years, publishing houses in French and Italian preferred books with a more universal resonance that played down specific Jewish suffering. By contrast, publishers in the new Jewish state preferred Holocaust accounts that comported with the Zionist narrative of struggle and resistance to memoirs of hiding and escape. Therefore Leyb Rochman’s gripping 1949 Yiddish-language memoir, The Pit and the Trap: A Chronicle of Survival, about how Polish petty crooks and prostitutes helped him and four other Jews survive elicited very little interest when it was translated into Hebrew. Jews who hid, and small-town, traditional Jews at that, were less interesting than the young Zionists who fought.

When Primo Levi presented his memoir of Auschwitz, If This Is a Man (Survival in Auschwitz), immediately after the war, it was turned down by Natalia Ginzburg’s well-known Einaudi and five other publishers before a small publisher accepted it. (In his memoir, Levi described his nightmare that when he returned to Italy, no one would be interested in hearing his story.)

By the mid-1960s, Jewish life writing about the Holocaust in all its diversity began to find both a Jewish and a non-Jewish audience. There was a sudden, new surge of interest in Levi, as well as in the memoirs of fellow Auschwitz survivor Elie Wiesel.

Levi and Wiesel did not know each other, and their memoirs were quite different. Levi, a trained chemist, wrote careful, detailed, precise descriptions of what he observed: how the camp functioned, its rules of survival, its debasement of language, and the diabolical ability of the Germans to recruit some prisoners to debase and crush the rest.

Wiesel’s Night, in contrast, was a spare account that focused on one main character, the young Elie himself. The excerpt from Night in the Posen Library includes one of its best-known passages, when Wiesel and his fellow inmates are forced to watch the hanging of a small boy and two other prisoners. The boy dies slowly, and as one prisoner nearby asks where God is, a voice from within the young Wiesel answers that God is on the gallows. This story of a young boy, his education in hell, and his improbable survival became, like Anne Frank’s diary, an iconic Holocaust book.

Migration in Postwar Jewish Writing

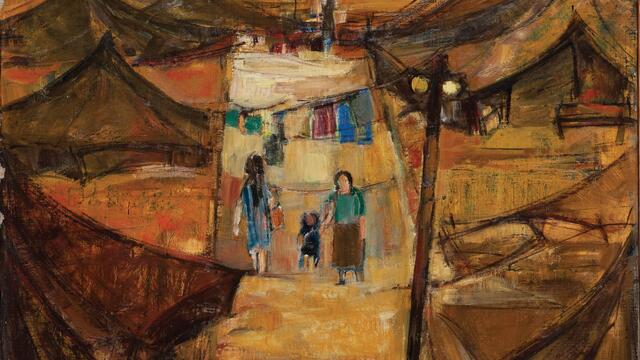

An important example of life writing in postwar Europe focuses on the mass migration of North African Jews to France and the ensuing transformation of French Jewry, which became Europe’s largest Jewish community. The tug of war between different identities—Jewish, French, Tunisian—is explored by Albert Memmi in his 1962 Portrait of a Jew. Sobered by his encounter with Tunisian as well as French antisemitism, and disillusioned with Europe and its false promises of universalist humanism, he recovers his agency through a reengagement with the complexities of a Jewish identity, which he comes to realize is much more consequential than he had imagined. Even as Memmi struggled to find his way, other Jews from Arab lands still looked for a means to preserve their Arab cultural heritage and maintain the rapidly fraying age-old ties. In a last letter penned on the eve of his execution in 1949, an Iraqi Jewish communist, Sasson Shalom Dallal, still hoped that revolution would allow Jews to live together with their “fellow Arabs.” But in fact, centuries of Jewish settlement in Iraq and other Arab-speaking lands were rapidly coming to an end.

However, memories endured. Jacqueline Shohet Kahanoff’s “A Letter from Mama Camouna,” written in Israel in 1968, explores Jewish identity through an extended family tour through space and time: Tunisian Jews move to France, Israel, and Egypt but remain linked by photographs, by letters, and by common memories that merge into what Kahanoff calls a “Levantine” sensibility. That very space becomes, in Kahanoff’s exquisite writing, an extraterritorial counterpart to unwelcome labels such as Ashkenazi or Mizrahi that failed to capture the nuance and charm of the Levant, rooted in a rich interplay of space, time, and language.

Jewish Life Writing in the Soviet Realm

Life writing assumed special importance behind the Iron Curtain, where growing state antisemitism dispelled any lingering Jewish hopes in communism. Accounts of visits to native shtetls, such as that of Gulag-survivor Shmuel Gordon, often slipped taboo details past the censors, such as broad hints about widespread participation of neighbors in the killing and plunder of Jews. Nadezhda Mandelstam’s Hope against Hope defiantly rejected the myth, still held in the 1950s by hopeful Soviet intellectuals, that Stalin’s terror was an aberration and not an essential part of a criminal system begun by Lenin.

Ilya Ehrenburg reflects on what he calls the worst time of his life, the late 1940s and early 1950s, when mass arrests decimated the ranks not only of Yiddish writers but also of Russian Jewish intellectuals like himself. Ehrenburg wrote his memoirs after Stalin’s death, so he was well aware of rumors that he owed his survival to his usefulness as a “court Jew” and even to his status as an informer. In trying to dispel these suspicions, he reveals striking details about Stalin and about the stubborn persistence of official antisemitism even after Stalin’s death.