Early Modern Rabbis and Intellectuals on the Move

Carrying books and knowledge, itinerant rabbis and scholars traveled between communities, facilitating cultural exchange.

The migration of rabbis and other intellectual figures played an important role in the cultural development of early modern Jewish society. Some of them traveled extensively, wandering among cities and countries. In the words of David Ruderman: “Jewish intellectual life and cultural production were shaped to a great extent by Jewish intellectuals who moved from place to place.”1 In some cases, their travels defined their lives. The list of itinerant Torah scholars and rabbis in this period includes central figures such as Don Isaac Abravanel, Joseph Karo, Isaac Luria, and Israel Sarug.

Some of these rabbis traveled as part of mass migrations and as a direct consequence of expulsions and persecution. Others were motivated by the desire to meet other scholars, to find publishers for their writings, or to obtain a suitable position to support themselves. In some cases, these relocations overlapped with significant transformations in their lives, such as conversion to Christianity or return to Judaism. Intellectuals among the Iberian New Christians were highly mobile. Some of them left Iberia or, conversely, moved back to Spain or Portugal from places where they had lived as Jews. One of the former was the well-known physician Amatus Lusitanus, who studied in Salamanca and worked as a doctor in Lisbon. He moved to Antwerp in 1534 and then to Ferrara, having been invited by the Duke of Este to teach in the local university. After some time, he moved to Ragusa, then to Ancona, in the Papal States. While in Rome, he visited various Italian cities, including Florence, where, in 1551, he published the first volume of his major medical work, Curationum medicinalium centuriae septem, which describes a hundred cases of illness he had treated. By 1561, he had published another six volumes and had become known as one of the most innovative physicians of his day. The ascent of the anti-Jewish Pope Paul IV drove him to move to Ragusa, and around 1561 he arrived in Salonika, his final destination. There, apparently, he openly reverted to the Jewish religion. He died of the plague in 1568, after expressing sorrow that he could not be buried in Portugal, his homeland.

The biography of Joseph Solomon Delmedigo (1591–1655) offers another fascinating example of an itinerant scholar, some of whose travels were driven by a desire to expand his learning. Born in Candia, Crete, in 1591, Delmedigo studied medicine at the university in Padua, where he attended Galileo’s lectures in astronomy. He moved to Venice and then returned to Candia. From there he turned to the Near East, first traveling to Alexandria and Cairo and then to Istanbul. Later he visited the Karaite communities (Jewish dissidents that rejected rabbinic authority beginning in the late eighth century) of Eastern Europe. In 1623, he arrived in Amsterdam, and in 1629, he published Sefer Elim (The Book of Elim; see Numbers 33:5), a scientific and philosophical work. He was a multifaceted writer, scientist, philosopher, and kabbalist, with an impressive knowledge of music. He died in Prague.

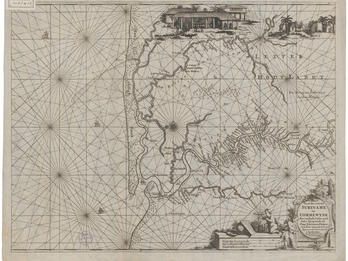

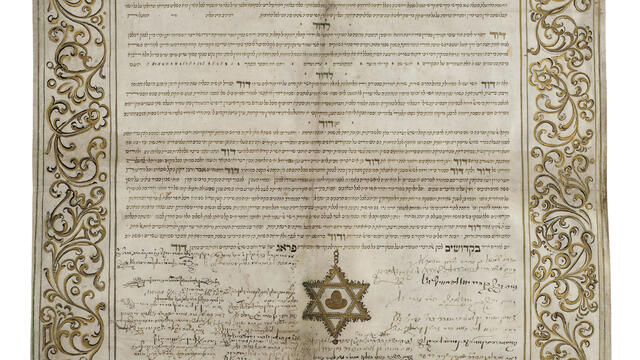

The rabbis Isaac Aboab da Fonseca and Moses Raphael d’Aguilar were both born in Portugal to Marrano families. Da Fonseca arrived in southern France with his parents as a child, and in the second decade of the seventeenth century they moved to Amsterdam and the whole family returned to Judaism. In 1626, da Fonseca was appointed rabbi of one of the Sephardic communities in the city, and later, between 1642 and 1654, lived in Recife, Brazil, where he was the first rabbi of a community in the Americas until the Portuguese conquest of the city. D’Aguilar, too, came to Amsterdam from Portugal as a child. He excelled in religious studies and acquired a broad education in classical philosophy as well. He accompanied da Fonseca to Brazil and served there as cantor of the community. Upon their return to Amsterdam, both served as rabbis in the Sephardic community. Da Fonseca was appointed chief rabbi in 1660 and served in that capacity until his death in 1693.

Compared to da Fonseca and d’Aguilar, the life of their colleague in the Amsterdam rabbinate, Jacob Sasportas, was even more marked by extensive wandering. Moving from North Africa to Europe, his career highlights the very different roles of rabbis in North Africa and in the communities of the Western Sephardic diaspora. He was born in Spanish-ruled Oran, North Africa, around 1610, to an aristocratic Sephardic family, in a community of just a few hundred Jews. He passed some of his early years in Tlemcen, where he acquired a talmudic education and bathed in the glory of his lineage as a descendant of the famous Jewish scholar Naḥmanides. There he served as ḥakham—rabbi—of the Jews of Oran and Tlemcen, as well as the surrounding area. Sasportas arrived in Amsterdam in 1651 and was first employed as a proofreader in the pioneering printing house of Menasseh Ben Israel, a leading Sephardic rabbi, today primarily known for his role in securing the official return of Jews to England. In 1655, Sasportas moved to Salé, Morocco, apparently as the business representative of a group of merchants from Amsterdam. He remained there until 1664, although in 1659 he had already traveled to Spain as an emissary of the ruler of Marrakech. He returned to Salé, then moved to London, as he was invited to serve as the rabbi of the young Jewish community there. However, his stay in London was cut short by a severe outbreak of the plague. This time he went to Hamburg, where he stayed as the rabbi of the Sephardic community until 1666. He became a fierce opponent of Shabbetai Tzvi and waged an uncompromising campaign against the rabbis who believed he was the messiah, sending vehement letters to them that also circulated very widely. In 1678, he accepted the invitation of the Sephardic community of Livorno to serve as its rabbi, but his relations with local leaders quickly deteriorated, and in 1680 he returned to Amsterdam, his final resting place. He joined the local rabbinic court and, after the death of R. Isaac Aboab da Fonseca in 1693, was appointed chief rabbi.

Travel could be spurred by engaging in trade and facilitated by the personal contacts—both Jewish and non-Jewish—it produced. Printing, like other commercial activities, was part of a larger social context, and printers—who were sometimes also scholars themselves—were often involved in marketing their goods. Jacob Abendana, for example, born in Hamburg, lived in Amsterdam for some time before moving in 1680 to London, where he was invited to serve as rabbi of the Sephardic community. Not coincidentally, Abendana had already visited England, as a bookseller; in 1662, he was in Oxford selling books and manuscripts to a series of Christian Hebraists, with whom he maintained contact over the years. Among his clients were Johann Friedrich Mieg, who taught theology in Heidelberg; Edmund Castell, who taught Arabic at Cambridge; and even Henry Oldenburg, secretary of the Royal Society in London. The latter introduced him to Thomas Barlow, the librarian of the Bodleian Library at Oxford. Jacob Abendana’s visits to Oxford also opened the way for his younger brother, Isaac Abendana, who lived there but later moved permanently to Cambridge, where he taught Hebrew. The book trade brought Jacob Abendana to other places, too. In 1659, he sold books in Leiden to Professor Johannes Cocceius and made a close connection with the greatest Christian Hebraist of his generation, Johannes Buxtorf the Younger, at the University of Basel.

In comparison to these Sephardic rabbis, the wanderings of Shabbetai Meshorer Bass and Nathan Hannover were relatively restricted. Their families were murdered between 1648 and 1655 during the Cossack Rebellion and subsequent wars. Shabbetai Bass was born in Kalisz and moved to Prague after 1655. His musical talents and his deep voice led him to the choir of Prague’s Altneuschule (Old New Synagogue), where he acquired the surname Bass. Between 1674 and 1679, he passed through Głogów, Krotoszyn, Leszno, Poznań, and Worms, before reaching Amsterdam, in 1679, where he came into contact with both the Sephardic and Ashkenazic communities. Working as a proofreader in the printing house of Uri Phoebus, in 1680, he published Sifte ḥakhamim (Lips of the Wise; see Proverbs 15:7), a popularized version of Rashi’s commentary on the Torah and the Five Scrolls (Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, and Esther). In the same year he also published Sifte yesḥenim (Lips of the Sleepers; see Song of Songs 7:9), a list of more than 2,200 books, in alphabetical order, with the authors’ names, place of printing, and short summaries of the contents. This book is rightly considered the father of Jewish bibliography. In addition, having wandered on the roadways of Europe, he published a Yiddish guide for travelers, Masekhet derekh erets (Tractate of the Way of the World). It contains descriptions of the different coinages, weights, and measures in various countries, distances between major cities, and available means of transportation—and, of course, the prayers that a Jew must recite daily.

Nathan Hannover, the author of a well-known chronicle of the pogroms of 1648–1649, Yeven metsulah (Abyss of Despair) was born in Ostróg, Volhynia. He fled to Lithuania after the Cossack riots, and from there he traveled to Prague, and on to Venice, where he studied kabbalah with Moses Zacuto. He continued to Moldavia and was appointed the rabbi of Iași in Walachia. Later he served as a rabbi in Ungarish Brod, where he was killed by Turkish soldiers. While living in Prague, he published Safah berurah (A Pure Language), a Hebrew-German-Italian-Latin dictionary, for Ashkenazic Jews who were wandering on the trails of Europe.

Notes

David B. Ruderman, Early Modern Jewry: A New Cultural History (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2011), 41.