Early Modern Visual and Material Culture

Early modern Jewish visual culture flourished, with illuminated manuscripts, ornate synagogues, and portraiture alongside increasing non-Jewish interest in Jewish customs and greater Jewish self-representation.

During the early modern period, Jewish material culture was greatly enriched, as evidenced by the color and black-and-white images for this period in the Posen Library. Printing contributed decisively to this development. Jewish books became an accessible commodity. Not only did they reach far more Jews than in the past, but they also were acquired and read by Christian scholars, who showed an increasing interest in the study of Jewish texts, postbiblical Jewish literature, and Jewish customs and ceremonies. Christians continued to engage in polemical exchanges with Jews on religious matters, in hopes of converting them to Christianity. But attitudes were beginning to change. From the seventeenth century on, as Richard I. Cohen has demonstrated, a new attitude toward Jews and Judaism began to emerge among non-Jewish travelers and artists, mainly in Western Europe; they began to describe and depict Jews and their culture with some impartiality. Although still subject to the old prejudices, many non-Jews nevertheless showed a curiosity about Jewish life and behavior, desiring to portray what they encountered in as objective a way as possible.

For their part, Jews became increasingly aware of the great interest that their behavior and customs aroused within the surrounding society. Some responded by attempting to portray Jewish society in a positive way to non-Jews. Most likely this played a considerable part in the printing of fine editions of books and in commissioning splendid manuscripts from skilled artists and calligraphers. Five examples of manuscripts of Passover Haggadahs, copied and illuminated by Jewish artists in northern Italy, Candia, Vienna, Rome, and Altona (which then belonged to Denmark) are presented here. The Haggadah from Altona, which dates from 1740, is the work of a scribe and artist, Joseph Leipnik, originally from Moravia, who left behind thirteen Haggadahs that he both copied and illuminated.

Among the colorful manuscripts presented, the reader will find ketubot (marriage contracts) from many places, including Rome, Damascus, Venice, Bayonne, and Crimea. The ketubah from Hamburg dates from 1690 and is outstanding in its unique beauty. It was written for the wedding of Samuel de Isaac Senior Teixeira and Rachel Senior de Mattos. The splendor of the illumination reflects the vast wealth of the two families united by the marriage.

The reader will also find the medical diploma—which includes a portrait of the recipient of the degree—granted to a Jewish student in 1695 by the University of Padua. Another opportunity for artistic expression were the scrolls of the book of Esther, read ceremonially in the synagogue on the holiday of Purim, which first began to be decorated in the sixteenth century. We present here several gorgeous examples of painted or engraved scrolls of the book of Esther, including one produced by the noted Jewish artist Shalom Italia. A kabbalistic genre going back to the thirteenth century is that of ilanot (sefirotic trees), which depict the inner processes of the divine in the shape of a tree, or tree of life. Included here are three astonishingly elaborate examples.

Synagogues

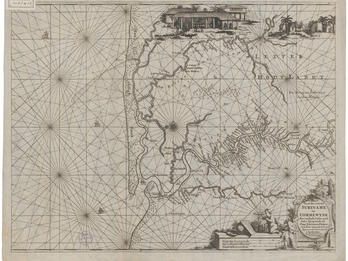

The section also includes photographs of synagogues from the four corners of the world. These synagogues were built during the early modern period in Christian countries, in the Muslim world, and as far away as Cochin, India. An interesting aspect of nearly all these synagogues is their deceptively dull exteriors, which contrast strikingly with the magnificent interiors. These interior spaces range from elaborately painted wooden ceilings from German lands, to baroque Italian rooms, and to the sand floors of the Caribbean synagogues. Moreover, some of the most splendid synagogues, like that of the Levantine Jews in Venice and the Sephardic synagogue in Amsterdam, were designed by well-known non-Jewish architects.

The synagogue of the Sephardic congregation in Amsterdam, the Esnoga, was inaugurated with great pomp and ceremony in 1675. It attracted many non-Jewish visitors and a number of Dutch artists painted it. We also present one of the three paintings done by Emanuel de Witte, who specialized in pictures of churches. The architecture of this synagogue was also the inspiration for the other Sephardic synagogues, such as the Bevis Marks synagogue in London and several in the Caribbean.

Funeral Monuments

We also present a small but representative selection of funeral monuments of various kinds: the gravestones of famous rabbis, such as Judah Loew (the Maharal) and David Ganz, who are buried in Prague, and Ezekiel Katzenellenbogen, buried in the splendid cemetery in Altona, which holds, unusually, both Sephardic and Ashkenazic tombs. This section also contains an outstanding selection of the ornate gravestones in the Sephardic cemetery in Ouderkerk, near Amsterdam. Black-and-white images of more gravestones, and texts of their inscriptions, can be found in the section “gravestones,” in Religious Practices.

Portraiture

In this period, Jews—especially members of the economic elite—evinced a desire and willingness to pose for artists who painted their portraits. As Richard Cohen has also described, European and Jewish society developed a new appreciation for the individual and the self. Some Jews began to be interested in having their portraits painted, as part of what has been called the “democratization of the portrait.” Among the portraits presented is a painting by Rembrandt, thought to be of the Sephardic Jewish physician Ephraim Bueno; another is the work of Rembrandt’s gifted student, Nicolaes Maes, who painted the wealthy Portuguese Jewish merchant, Francisco Lopes Suasso, as a young man. In addition, the Dutch landscape painter Jacob Ruisdael painted the Sephardic cemetery in Ouderkerk.

In this period, a few Jews were themselves painters who left behind works of value. Catherine da Costa (1679–1756) of London, the daughter of the physician Fernando Mendes da Costa, painted a number of portraits, including one of her father and a self-portrait, as well as a number of miniature portraits. Aron de Chavez, who was also active in London in the early eighteenth century, produced a painting of Moses and Aaron and the Ten Commandments, which is in the Bevis Marks synagogue in London.