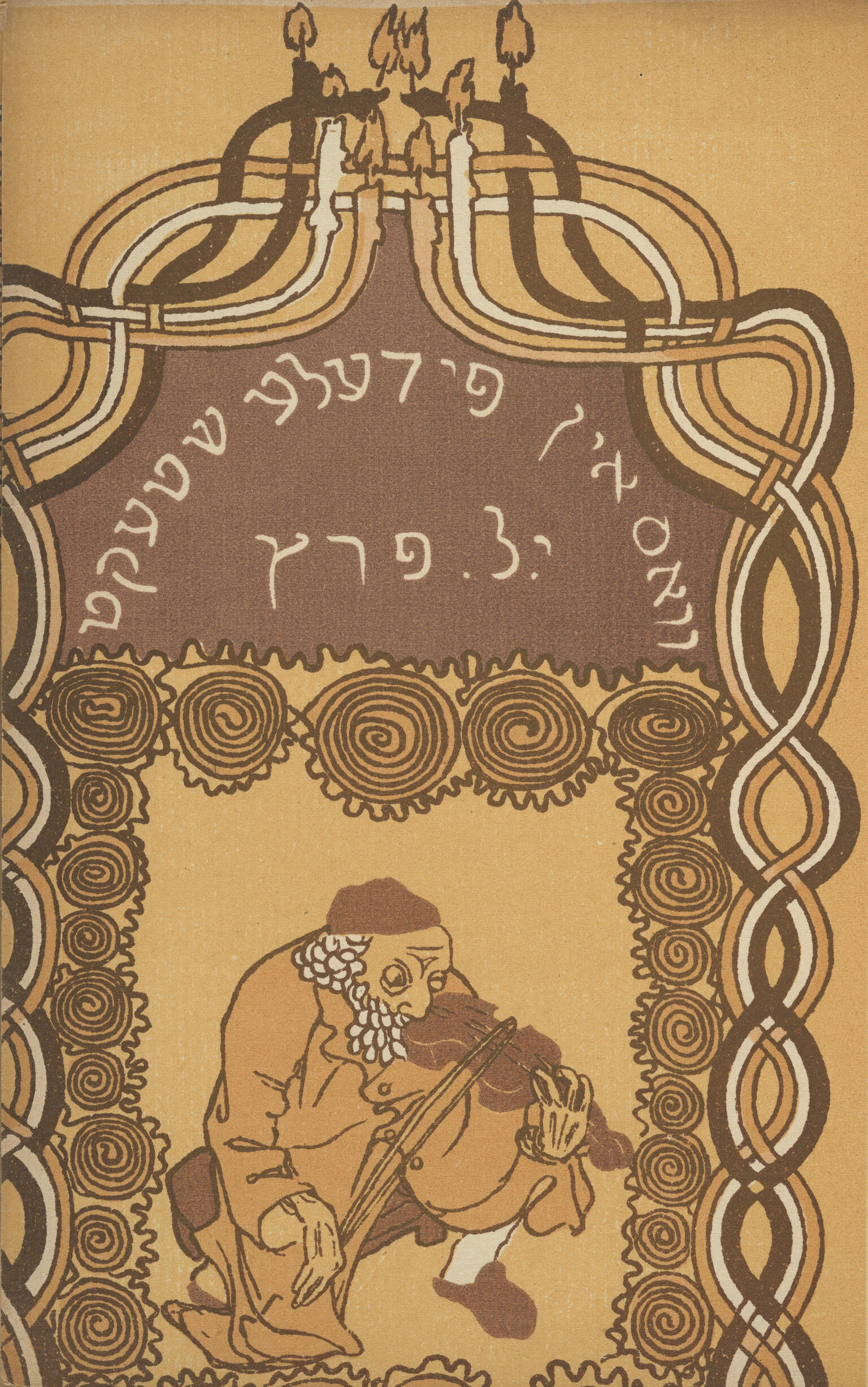

Cover Illustrations for Peretz's Dramen

Ber Kratko

Y. L. Peretz

1910

Places:

Related Guide

Jewish Visual and Material Culture at the Turn of the Twentieth Century

Increasingly culturally integrated, Jewish fine artists, designers, and photographers produced dazzling works of art and considered cultivating a distinctive national art.

Creator Bio

Ber Kratko

Born Aron Ber (Bernard) Szymon Kratko (Kratka) in Warsaw to a poor, traditional religious family, Ber Kratko apprenticed as a lithographer at the age of twelve. From 1901 to 1906, he studied at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts under Xawery Dunikowski, and then, after a two-year sabbatical touring Palestine, Egypt, and Italy, he appears to have studied in Berlin under Max Liebermann, perhaps informally. Returning to Warsaw around 1909, Kratko made contact with the Yiddish literary and cultural circle around the era’s preeminent Yiddish writer Y. L. Peretz; it was in this context that he produced the striking series of cover illustrations for a 1910 edition of Peretz’s dramas. Founding an artists’ group called the Jewish Artistic Circle around 1910, he would later help establish the Ukrainian National Academy of Fine Arts and Architecture in 1917, and thereafter make a career in the Soviet academy, focusing primarily on sculpture.

Creator Bio

Y. L. Peretz

A Hebrew-turned-Yiddish writer of short fiction, essayist, dramatist, and poet, Yitshok Leybush Peretz was the most influential figure in the Yiddish literary world of his day and the leading theorist, activist, and culture hero of the Yiddishist cultural movement. Born in Zamość, Russian Empire (today in Poland) to a merchant family, he received a fine traditional education while gaining access to modern thought as well as Polish and German literature. In the 1870s, after dabbling in Hebrew poetry, he became a successful lawyer in Zamość, where he maintained a Polish-language home with his second wife, Helene, and adopted Polish assimilationist ideals. In the mid-1880s, a combination of factors, including his disbarment for his ideological views, drove him to Warsaw and back to Hebrew literature—and fatefully to Yiddish literature as well. Even as he emerged in the mid-1880s as a much more innovative Hebrew writer and poet than before, Peretz produced—to a mix of fascination and shock among his fellow modern Jewish writers—the first truly modern poem in Yiddish, the startling “Monish.” In this same period, Peretz also produced the first great work of Yiddish-language reportage, “Impressions of a Journey through the Tomaszow Region in 1890,” and began to write the Yiddish fiction for which he would be most famous. In the 1890s, Peretz produced a series of largely self-composed periodicals, in Yiddish with one exception, that mixed social criticism of an enlightenment and socialist bent with critical realist fiction and unsettling indictments of Jewish passivity and parochialism (like “The Golem”). Simultaneously, he pushed the boundaries of Yiddish literature with delicate, if derivative, Heinesque lyric poetry and complex psychological fiction.

With his home in Warsaw already a site of pilgrimage for an emerging younger generation of Yiddish writers, Peretz began a new era in Jewish cultural life from the turn of the century with a corpus of deeply influential short stories that transposed East European Jewish folk culture and the stories of the Hasidic movement into a secular-national neo-Romantic vein. These stories made Peretz famous then and later as the champion of the idea that the ethical and aesthetic riches of traditional East European culture could provide the foundation on which to build a modern secular-humanist Jewish culture. Yet at the same time, he confronted his adoring readers with stories, dramas, and memoirs marked by formal difficulty and a starkly tragic sensibility.

Throughout the final two decades of his life, Peretz worked tirelessly to reshape Jewish culture as an editor, literary critic, advocate for quality Yiddish drama, and above all guide to multiple cohorts of younger writers, including Avrom Reyzen, H. D. Nomberg, Sholem Asch, I. M. Weissenberg, and Alter-Sholem Kacyzne. Peretz never ceased to write publicistic work that addressed concrete problems in Jewish life, indicted conservatism and intolerance while also warning against revolutionary sectarianism and fervor, found hope in any sign of Jewish cultural vitality, defended the importance of art in itself, and advocated the ideal of a diasporic Jewish cultural-national revival in Yiddish. In his lifetime and for a generation after, he embodied the possibility of a genuinely modern Yiddish literature capable of articulating all human concerns in every genre and the possibility of a secular-humanist Jewish national culture rooted in the diasporic past but bound in a mutually vitalizing relationship with other cultures and with modern ethical, aesthetic, and social ideals.

You may also like

Leshone-toyve shifskarte (Jewish New Year's Card in the Form of an Ocean Liner Ticket)

Publisher's Stamp

To the Majesty and Glory of Baron Hirsch (Lithograph)

Table Lamp with Elaborate Silver Lampshade

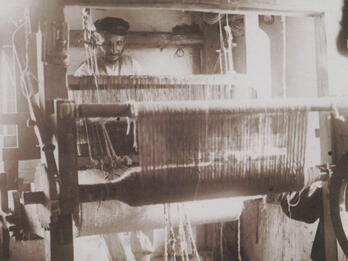

Tallis Weaver