Forged Identities in Nazi-Occupied France

Olga Kagan-Katunal

1942

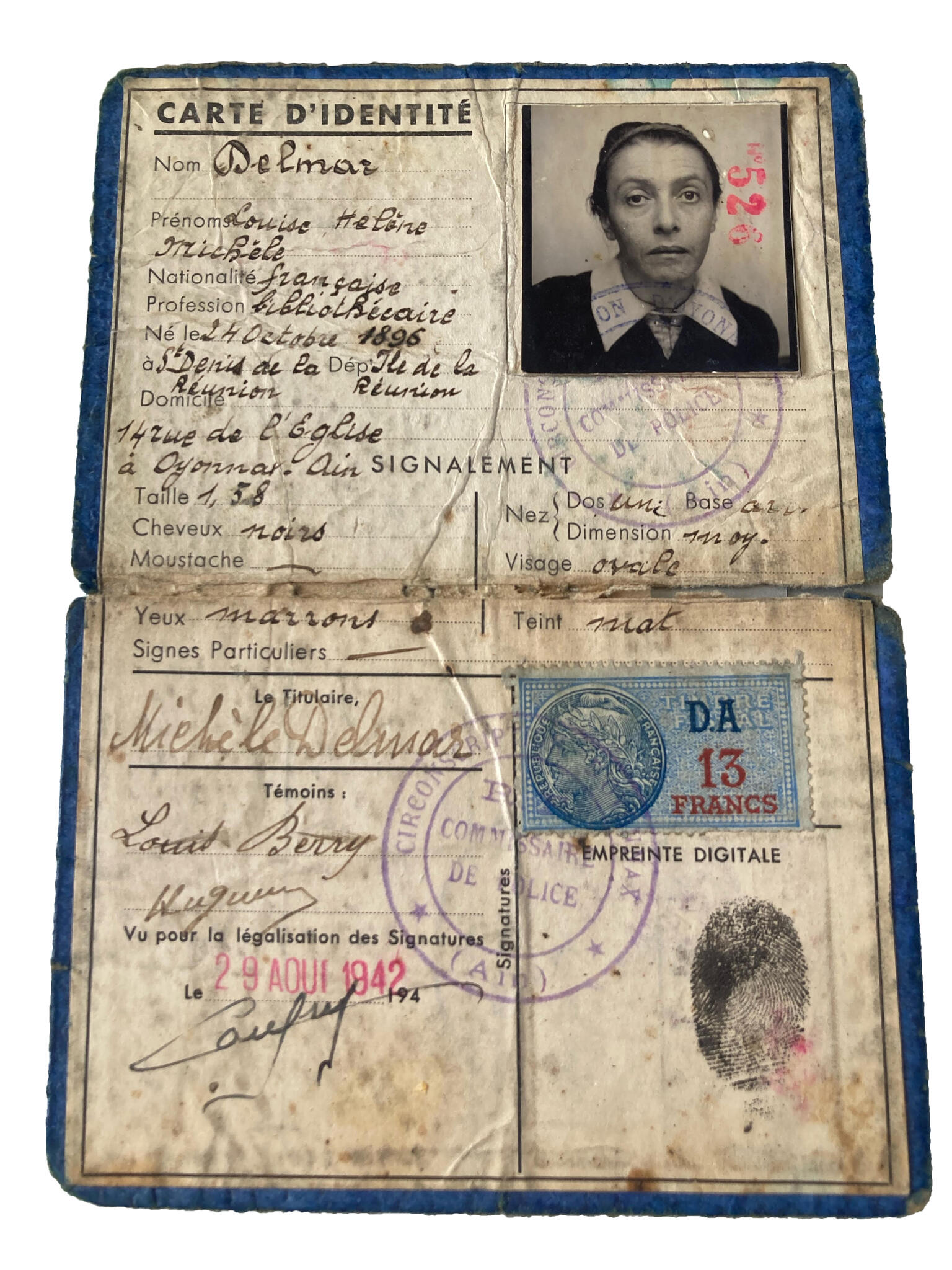

Across Nazi-occupied Europe, Jews were forced to register and carry identity cards marking them for persecution. Forgery and carrying forged papers became acts of survival and resistance. Olga Kagan-Katunal, a Lithuanian-born Jewish activist in France, refused to register and went into hiding, assuming a French identity within the Resistance. Using two forged IDs—one from La Réunion and another from a central French village—she relied on the latter for protection. Throughout the war, she helped produce false papers that saved fellow Jews and political dissidents from arrest and deportation.

Examine the two identity cards carefully. What elements make up each card, and what do they reveal about their holders’ identities? How do the two cards differ?

Forged papers alone did not guarantee survival. What else might have mattered? How might Kagan-Katunal’s experience as a highly educated, multilingual Resistance fighter have differed from others’?

What role might gender have played in shaping resistance work, particularly document forgery?

Creator Bio

Olga Kagan-Katunal

Olga Kagan-Katunal was a translator, political activist, and philosopher. She was born in Libau (Liepāja), Latvia, to a well-to-do and mostly nonobservant Lithuanian Jewish family, becoming fluent in Russian, Yiddish, English, Polish, and German and learning some Hebrew and French. In 1921, she moved to Berlin, where she lived an unconventional life and became friendly with followers of the Jewish philosopher Oskar Goldberg. She moved to Paris, where she worked as a secretary and translator, though she returned to live in Berlin but fled to Riga when Hitler came to power in 1933. In 1920s Paris, Olga had joined the Communist Party, helping them with Soviet propaganda in the 1930s. Her younger brother Alexander, who lived in Moscow, was executed in 1938 during a Stalinist purge. In 1940, two days before the Germans entered Paris, she fled to Bordeaux but decided to return to Paris. There she joined a French left-wing resistance group that helped Jewish and non-Jewish refugees and escaped prisoners flee to nonoccupied regions, providing them with false papers. The group was denounced in 1943, but Olga avoided arrest and, hiding in occupied Paris, continued to help fleeing Jews. After the war, she became a scholar and translator of Jewish texts, studying with rabbis and corresponding with Oskar Goldberg. She died in Paris, where she is buried. In 2022, she received the posthumous title of Guardian of Life from the French Jewish community for having saved Jews during the war.