Early Modern Jewish Languages

As Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews migrated eastward, Yiddish and Ladino emerged as distinct languages. Both languages developed literary traditions, as print became more widespread.

A large demographic shift was taking place in the early modern period; much of Jewry was moving eastward, Sephardim toward the Ottoman Empire and Ashkenazim toward the Polish Commonwealth (Lithuania). In both cases, Jews spoke languages that they brought with them, Ladino in the first and Yiddish in the second. The result was a linguistic distance between Jews and their host societies that had not existed in the medieval period—and would cease to exist in the modern period. Medieval Jews spoke (including among themselves) the vernacular of whichever country they lived. Jews in the medieval Islamicate world spoke Arabic, and in medieval Europe, Italian Jews spoke Italian, and French Jews spoke French. During the early modern period, however, the vast majority of Jews were speaking languages that few among the host societies could understand, and few Jews were entirely familiar with the languages of the hosts. Even in the German lands, western Yiddish grew apart from local vernaculars at least until the end of the eighteenth century. This phenomenon, which held true for most Jews during this period, stands in stark contrast to the increase in cultural interactions between some groups of Jews and the surrounding non-Jewish culture.

One exception was the Italian Jewish communities of Italy, where, beginning as early as the fourteenth century, Italian Jews had written, on occasion, literary works in Italian, sometimes using Hebrew characters. Another form that played with the interaction between two languages—and between two cultures—was macaronic poetry, here written in interspersed Italian and Hebrew. The early modern period saw further experimentation with Italian (and Latin as well) as a literary language by Italian Jews. Though far less extensively used than Spanish or Portuguese, this development resulted in a corpus of Italian translations and of literature—poetry, political discourses, ethics, scientific works, and more—written by early modern Jewish men (and women).

Literary Hebrew itself was not untouched by developments during this period. For example, an elegant and intricate literary form of Hebrew arose, which served as the language of rabbinic correspondence and poetic and liturgical creativity in the Ottoman Empire, North Africa, and the Western Sephardic communities. Prosodic norms based on Arabic quantitative metrics had governed the composition of nearly all Hebrew verse since the tenth and eleventh centuries; these were giving way to new poetic forms and new Hebrew prosodies, based on the Italian sonnet, for example, or on Spanish and Turkish folk music.

Another phenomenon entirely anchored in Jewish society of the early modern period is the development of literature in two new Jewish languages: Ladino and Yiddish. Ladino (Judeo-Spanish, also called Judezmo), evolved after the expulsion of Jews from the Iberian Peninsula among the Sephardic refugees, who began to populate the lands around the Mediterranean, especially the Ottoman Empire. Yiddish followed the mass migration of Jews from the states of Germany. The printing industry played an important role for both nascent languages. A rich corpus of books was published in Yiddish and—in parallel, though far fewer—in Ladino as well.

Ladino

During the medieval period, Jews of the Iberian Peninsula did not have a solid collective identity. As Jonathan Ray has put it: “Sephardic society was more a product of the sixteenth century than of the Middle Ages. Prior to their expulsion, Spanish Jews comprised a loosely associated collection of communities with little cohesive identity. . . . Perhaps the greatest example of Sephardic culture as a product of the post-Expulsion era rather than its medieval predecessor was the development of a shared language.”1 Before the expulsion, Sephardic Jews—like their non-Jewish neighbors—had spoken (and sometimes written, usually in Hebrew characters) the local Iberian dialect. Among the Jews expelled from Spain and Portugal who ended up in the eastern part of the Mediterranean Basin, a Judeo-Spanish koine arose: Ladino. As a result of the dispersion into new lands, this language began to reflect the new linguistic environments, growing increasingly distant from Castilian and the other Iberian vernaculars. It included Hebraisms and Arabisms from the period before the expulsion and gradually came to include Greek and Turkish influences.

In general, books in Ladino published in the Ottoman Empire were printed in Hebrew letters and reflected a traditionally educated reading public. In Istanbul, for example, the 1547 Ladino translation of the Pentateuch was printed along with the weekly Haftara (passages from the prophets read during the Sabbath service). In 1568, in Salonika, a collection of passages from the Shulḥan ‘arukh, translated into Ladino, was published under the title of Mesa de el alma (Table of the Soul). And a Ladino translation of the eleventh-century ethical work Ḥovot ha-levavot (Duties of the Heart), by Baḥya Ibn Pakuda, was published in the sixteenth century as well.

Moses Almosnino, active in Salonika during the sixteenth century, left behind many works in Hebrew, Spanish, and Ladino. In 1564, he published his most important work, Regimiento de la vida (Regimen of Living), on the commandments and Jewish law—this too printed in Hebrew letters. The volume was published together with Tratado de los sueños (Treatise on Dreams), in which Almosnino discussed the connection between dreams and prophecy. In 1566, when he was in Istanbul, he wrote four historical texts in Ladino on the reign and death of the Sultan Süleyman, as well as on the rise of Selim II. Almosnino also wrote about the city of Istanbul and its characteristics, including the local Jewish community. In the seventeenth century, no Ladino literature was printed, but the works in that language, extant in manuscript only, testify to some continuing literary activity.

One of the most prolific writers in Ladino was Abraham Asá, who lived in Istanbul in the eighteenth century. Among other things, he translated the prayer book into Ladino under the title Bet ha-tefilah (The House of Prayer; Istanbul, 1739). He also wrote a comprehensive collection of coplas (poems in Ladino) entitled Sefer tsorkhe tsibur (The Book of Community Requirements), in which he set out all the commandments in rhyme. In 1739, he published a Ladino translation (in Hebrew letters) of the Bible, and by 1745 he had completed translations of all the books of the Bible.

The masterpiece of Ladino literature of that time is the encyclopedic commentary on the Bible Me‘am lo‘ez (From a People of Foreign Tongue), by Jacob Huli, the first volume of which was published in Istanbul in 1730. After Huli’s death in 1732, the project was continued by Isaac Magriso, who completed the commentary on Exodus, published in Istanbul in 1746. Commentaries on Leviticus (1753) and Numbers (1764) followed. This project, which continued until the end of the nineteenth century, became a cornerstone of Ladino culture and of Sephardic Judaism in the East.

Spanish

Sephardic Jews in Western Europe—as opposed to the descendants of the refugees who had settled in the Mediterranean and the Ottoman Empire—did not write in Ladino. Almost all of them were former New Christians or descendants of New Christians. Instead, they continued using Iberian languages throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. They wrote literary works in Spanish and Portuguese—and also in Hebrew, which they specially cultivated.

The members of the Sephardic communities from Italy westward were almost all former conversos who returned to Judaism. While living as Christians in Spain and Portugal, they had undergone comprehensive Catholic socialization, and most were well educated in the Iberian languages. Indeed, some of them studied in leading universities such as Coimbra in Portugal and Salamanca and Alcalá in Spain, as well as in Jesuit seminaries and other select Catholic institutions.

When they returned to Judaism in Amsterdam, Hamburg, Livorno, Venice, London, and other cities, they continued to write in the languages of their upbringing, at least until the beginning of the eighteenth century. Portuguese, the mother tongue of most of the Marranos, remained the main language of their daily life, as well as the language used for announcements in the synagogue and for writing in community registers. Spanish was their literary language, used for instructing children and for the Bible translations used in their schools. Naturally, Hebrew words entered their Spanish and Portuguese, mainly vocabulary connected with religious ritual, but in Western Europe, these languages did not become an internal Jewish dialect.

In the sixteenth century, some works were printed specifically to teach former conversos how to return to the bosom of Judaism. A few Jewish books in Portuguese were published in the Sephardic center in Ferrara, established during the first half of the sixteenth century, but its pride and glory was the 1553 Spanish translation of the Bible, printed in Latin letters, now known as the Ferrara Bible. This was perhaps the most important literary project of the sixteenth century in Judeo-Spanish. The literal and word-for-word translation was based on the Masoretic text.

A prayer book in Spanish was published in Ferrara as early as 1552, and during the seventeenth century several editions of the daily and holiday prayer books were published by Jewish printing houses in Amsterdam. Religious services in the synagogues of these communities were conducted in Hebrew, but those who had not yet learned Hebrew followed the cantor from prayer books translated into Spanish, which could be found in every single community.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, nearly four hundred books were published in Iberian languages in Amsterdam. Some were translations of basic Jewish sources, ethical and philosophical works, but most were original works by members of the Sephardic diaspora such as those by Menasseh Ben Israel, Jacob Judah Leon Templo, Abraham Israel Pereyra, Isaac Cardoso, and others.

A good deal of Spanish poetry (as well as Hebrew) was written by talented poets who sought, with considerable success, to imitate the Baroque style prevalent in the Spanish kingdom. David Abenatar Melo was born in Portugal, imprisoned by the Inquisition in Spain, and returned to Judaism in Amsterdam in 1612. After settling in Hamburg, he published an impressive Spanish adaptation of the book of Psalms. Manuel de Pina, a writer and musician who was born in Lisbon and returned to Judaism in Amsterdam, was a talented poet in both Spanish and Portuguese. His Chanças del ingenio y dislates de la musa (Witty Jests and the Muse’s Nonsense), a 1656 book of Spanish verse, was banned because some of the poems were too risqué and contained vulgar language. Daniel Levi de Barrios, a native of Andalusia who arrived in Amsterdam in 1662, was undoubtedly the greatest poet among the Western Sephardic Jews. He published some poetry under his Christian name, Miguel de Barrios, and several of his works were distributed in Brussels and Antwerp, then under Spanish rule. He also wrote plays, including religious ones, modeled on Catholic autos-sacramentales but with decidedly Jewish content. He published a series of poems about the history of the Sephardic community, its institutions, and its societies entitled Triunfo del govierno popular (Triumph of the People’s Government; 1683). As late as the eighteenth century, a talented poet, David del Valle Saldaña, wrote both religious and secular poetry in Spanish, showing that the language still thrived in the community.

The most important prose writer among the Sephardim in Western Europe was Joseph Penso de la Vega, who wrote stories in Spanish and—in his youth—a play in Hebrew called Asire ha-tikvah (Prisoners of Hope). He also penned a most original work, Confusión de confusiones (Confusion of Confusions), in which, with great wit and in a jocular tone, he wrote about the stock exchange in Amsterdam.

Finally, the Sephardic printing house of David de Castro Tartas published a newspaper, Gazeta de Amsterdam (Amsterdam Gazette), from 1672 to 1702. This periodical is regarded as the first Jewish newspaper in the world, although it had no explicitly Jewish content. It contained political and economic news of interest to the Sephardic Jewish merchants who were deeply involved in international commerce.

Yiddish

Historians of Yiddish language and literature define the period between 1500 and 1700 as a transitional one, called Mitl-Yidish (Middle Yiddish), which falls between Alt-Yidish (Old Yiddish) and modern Yiddish, known as Nay-Yidish (New Yiddish). During this period, Ashkenazic Jews—both those who moved to northern Italy and those who settled in Poland-Lithuania—used Yiddish as a language of daily communication and for ritual purposes, for Torah study, and for educating their children. In these new lands, Yiddish evolved away from German while absorbing influences of the languages of the new surroundings, mainly Slavic tongues. An eighteenth-century Christian scholar of Yiddish, Wilhelm Christian Chrysander, wrote that Jews in his time would boast that, by means of Yiddish, they could travel anywhere in the world. There were even Yiddish-speaking Jews in Scandinavia; the eighteenth-century Danish-Norwegian playwright Ludvig Holberg placed entire Yiddish sentences into the mouths of his Jewish characters.

One of the outstanding features of this period is the increasing divergence between the language used in printed books and the multitude of dialects in use in daily life. As Jean Baumgarten has written: “The pre-modern era, starting in the mid-sixteenth century, saw an increasing differentiation of the Yiddish dialects, particularly the distinction between western and eastern Yiddish. . . . The vernacular was spoken in Germany, but also in Alsace and Switzerland. It spread into Holland and the communities of northern Germany. The center of gravity of the Yiddish world gradually moved eastward, to what was becoming the central space of Ashkenazic Judaism. Yiddish was used in Bohemia and Moravia; it spread to Courland, Mazovia, Bielorussia, Ukraine, and also to Palestine, where it was spoken in the Ashkenazic community of Jerusalem.”2 Written Yiddish shows a gradual process of standardization, but its connection with various local dialects is evident in the printed texts. The development of printing at the same time that Yiddish began to be spoken in most parts of Europe required the formation of a literary koine, based on the norms of Western Yiddish, but at the same time meant to be understood by readers who still spoke various dialects.

One of the most important centers of Ashkenazic Jewry—and the Yiddish book—arose in northern Italy. Between 1545 and 1609, thirty-three books were published in Yiddish there, constituting more than a quarter of all Yiddish books printed at the time. Most were the work of the Venetian Christian printer Daniel Bomberg, originally from Antwerp. By the early seventeenth century, Ashkenazic Jews in northern Italy had stopped using Yiddish as their language of daily speech and literature, but during the previous century, those who lived in that region maintained an extensive and intense literary activity in Yiddish, mainly in Padua, Mantua, Venice, Verona, and Cremona.

The Jews of Poland pioneered the printing of Yiddish books. In Poland, where the largest Ashkenazic Jewish center of the early modern period would emerge, the first Yiddish books were printed in Kraków as early as the 1530s. The first of these appeared in Kraków in 1534/5: Mirkeves hamishne (The Second Chariot), a Hebrew-Yiddish glossary of the Bible. A year later, the first printed book of women’s commandments appeared in Kraków, called Azhoras noshim (Warning for Women), by David Cohen, and by the mid-seventeenth century, we know of at least nine editions of such books in Yiddish. From the 1530s until 1650, approximately two hundred Yiddish books were printed in Poland, including reprintings and short pamphlets. After Yiddish books were published in Kraków in the 1530s, they began to appear in other cities of the Ashkenazic diaspora. In the 1540s, Yiddish books were already being published in Isny and Konstanz, Augsburg, Ichenhausen, Venice, and Zurich. Most of the printing houses that produced these books were short-lived. However, during the sixteenth century, Yiddish books continued to appear in Venice, Basel, Cremona, Mantua, Sabbioneta, Prague, and Verona.

Women’s Yiddish Literacy and Literature

It is no coincidence that prominent among the first Yiddish books printed in Poland were those intended for women. Edward Fram has attributed this to the educational system in Ashkenazic society at that time, which did not teach women how to read rabbinic literature: “Even though universal formal Jewish education for boys was offered in some centers in the sixteenth century, girls did not enjoy the same privilege. Girls who learned to read most likely did so at home and generally did not progress beyond learning the Hebrew letters—all they needed in order to pray and read Yiddish texts.”3 Yiddish books thus came to fill a gap in women’s education, since access to rabbinic education was denied to them. Books written in Yiddish or translated from Hebrew sources provided a substitute for the study of canonical rabbinic literature for women. For example, Benjamin Slonik, who studied with the greatest rabbis in Poland in the sixteenth century, published a book of responsa, Mas’at Binyamin (Benjamin’s Portion; Kraków, 1633), as well as a handbook for women in Yiddish, Seder mitsvot ha-nashim (The Order of Women’s Commandments). This handbook went through several editions: Kraków in 1577, 1585, and 1595, and Basel in 1602, indicating its success and wide circulation. As Chava Turniansky has pointed out with respect to wealthy women, “Some Yiddish books were dedicated to particular women, and others were explicitly intended for women in general; from this and many other sources, we learn that at that time a large number of Jewish women, possibly even the majority, were literate, enabling them to play a considerable role in Yiddish literature as addressees and readers, and in supporting writers and their books.”4

At the end of the sixteenth century, a Polish Jewish woman, Rebecca Tiktiner, wrote an important ethical work for women entitled Meneket Rivkah (Rebecca’s Nursemaid; Prague, second half of the sixteenth century). The style of her book suggests that she had experience in giving sermons for women. She also wrote a Yiddish poem for Simḥat Torah.

Tekhines, a genre of petitionary prayer for women in Yiddish, which developed in Europe from the seventeenth century on, became very popular throughout the Ashenazic world. “There are two main groups of tekhines,” writes Chava Weissler: “first, those that appeared in Western Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and that were probably written or compiled by men for women; and second, those that originated in Eastern Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth, and early nineteenth centuries, some of which were written or reworked by women.” Weissler has defined the genre as follows:

Western European tekhines were published in collections addressing many topics, either in small books or as appendices to Hebrew prayerbooks, often prayerbooks with Yiddish translation. By contrast, Eastern European tekhines were typically much shorter, published in little booklets addressing one or two topics, usually on inexpensive paper with small, difficult-to-read type. Despite the differences, the Western and Eastern materials constitute a single genre. They use a special variety of Yiddish, sometimes called tekhine-loshn (“tekhine language”), and do not, as a rule, reflect local dialectical differences.5

Noteworthy Yiddish Publications

An important Yiddish book of biblical commentary, called Tsene rene, organized according to the biblical portion read in the synagogue each week, was written by Jacob Ashkenazi of Janov, near Lublin, probably at the end of the sixteenth century; it was published for the first time in 1622. The title derives from the Song of Songs: Come out and see, daughters of Zion (3:11), implying that the work is intended for women. The author combines homilies, interpretations, and legends from various sources, creating an attractive unity. By 1785, sixty-four editions of the book had been published.

According to Chone Shmeruk, Elye Bokher (known more generally as Elias Levita) was the most important creative figure in the history of Yiddish literature until the nineteenth century. He was born around 1468 in Neustadt, which is near Nuremburg, but he spent most of his life in Italy, mainly in Venice. He is primarily known for his publications in the field of Hebrew grammar and lexicography, and he was well known by virtue of his connections with Christian scholars. His Yiddish translation of the biblical book of Psalms was first published in Venice in 1545. He wrote several witty pasquinades in Yiddish, but his main works were Buovo d’Antona (Bovo of Antona), or Bovo-bukh and Pariz un Viene (Paris and Vienna). Both books are lyrical or chivalric novels based on Italian texts of stories that had been popular in southern Europe before reaching northern Italy.

The Jewish printing houses in Central and Eastern Europe were destroyed during the Thirty Years’ War and the pogroms against the Jews of Poland in 1648–1656. As a result, Amsterdam became the center of Jewish printing in general and of Yiddish books in particular. The Jewish printing houses of Amsterdam supplied Yiddish literature for the entire Ashkenazic world, including many books that were reprinted there after appearing elsewhere. Sometimes, in doing so, they attempted to avoid local idioms, displaying an awareness of developments that were taking place in the spoken language.

In the seventeenth century, in fact, Amsterdam emerged as the most important center of the Yiddish book by virtue of the flourishing of the local printing industry in general—and of Jewish printing in particular. Between 1644 and 1750, a total of 220 Yiddish books were printed in Amsterdam. Two of the most important were new, competing translations of the Bible, one by Jekutiel Blitz and the other by Joseph Witzenhausen. In 1686, the first Yiddish newspaper appeared in Amsterdam. It was published on Thursdays or Fridays, and thus called Dinstagisje oen Freitagisje Koeranten (The Kurant), and it primarily provided international news. In 1743, Menaḥem Man Amelander published, in Amsterdam, Sheyris Yisroel (Remnant of Israel), a comprehensive historical work in Yiddish, a sort of continuation of the medieval Hebrew book Yosifon, describing the history of the Jews until 1740. In 1725–1729, Amelander, along with his brother-in-law Eleazar Soesman, published Megishai minkho, a Yiddish translation of the Bible, with commentary.

The flourishing of Yiddish printing in Amsterdam, which also supplied books to the Jewish market in Eastern Europe, continued at least until the middle of the eighteenth century. Only at the end of that century did the status of Yiddish decline as the primary language of communication for Ashkenazim in Western Europe.

Notes

Jonathan Ray, After Expulsion: 1492 and the Making of Sephardic Jewry (New York: New York University Press, 2013), 7, 136.

Jean Baumgarten, “Continuity and Change in Early Modern Yiddish Language and Literature,” in The Cambridge History of Judaism, vol. 7, The Early Modern World, 1500–1815, ed. Jonathan Karp and Adam Sutcliffe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 276.

Fram, My Dear Daughter, 11. For boys, too, education was mainly private, and thus reserved for the affluent, at least until the mid-seventeenth century. However, even affluent families generally did not offer education to their daughters.

Chava Turniansky, “On Women and Books in the Early Modern Period” [Hebrew], Igeret no. 30 (Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 2009), 8.

Chava Weissler, Voices of the Matriarchs (Boston: Beacon Press, 1998), 7–8; Shlomo Berger, Producing Redemption in Amsterdam. Early Yiddish Books in Paratextual Perspective (Leiden: Brill, 2013), 23, 35, 49, 99, 176, 180–181, 196.

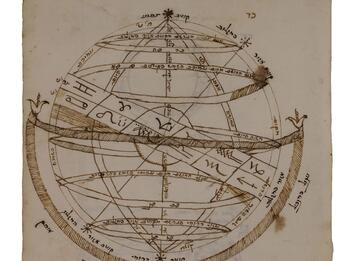

![M10 622 Manuscript, probably from Ukraine]. Manuscript probably from Ukraine, c. 1740 with a broad collection of practical kabbalah and mystical magic. Facing page manuscript arranged vertically with Hebrew text in the shape of a figure wielding two long objects.](/system/files/styles/entry_card_sm_1x/private/images/vol05/Posen5_blackandwhite166_color.jpg?h=cec7b3c9&itok=Sz6u21MQ)