Hellenistic-Era Jewish Literary Activity

Using Greek and Greek literary forms, Jewish authors expressed Jewish themes and ideas.

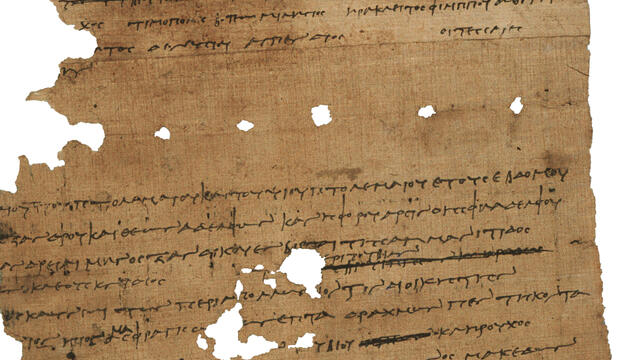

Much Jewish writing in the last centuries BCE consisted of adaptations of biblical material to Greek literary genres. Theodotus, for example, retold in Homeric language and meter the tale of Dinah, an appropriately Iliad-like biblical text. One Jewish author, named Ezekiel, composed a tragedy based on the story of the Exodus from Egypt; it is the only surviving postclassical tragedy. Others composed philosophical treatments of topics in Jewish theology, anticipating the much better-preserved writings of Philo of Alexandria. And Artapanus composed, somewhere in Egypt, a curious mythographic rewriting of the Joseph and Moses stories, both of which are set primarily in Egypt. Most of these books survive only in the form of brief excerpts quoted by much later Christian writers, and few of them can be located or dated with any certainty. Our texts attest to Jewish literary creativity in general, but they do not tell us a great deal about elite Alexandrian Jewish culture.

For one thing, some members of the elite may well have been less “Hellenized,” or even less literate, than these texts might suggest. Some may have been more so; they may have opted out of Judaism altogether. But the preserved texts remain suggestive. Their authors were committed both to a recognizable version of Judaism (all engage with the contents of the Pentateuch or the Hebrew Bible more generally) and to certain Greek cultural norms. The view that these texts were intended to convince a Greek audience of the excellence of Judaism has long since been abandoned. It was the Jews themselves who needed reassurance that Judaism was as good—as ancient, as beautiful, as Greek—as Hellenism. In this sense, these texts—which represent internal Jewish discourse—are as “authentically” Jewish as any other.