Diverse Diasporas in the Postwar Period

Jewish communities in North and South America, South Africa, and Australia navigated complex local politics while creating literature that preserved their Jewish heritage.

Even as the United States and Israel became the dominant centers of Jewish life in the postwar period, other diasporas continued to thrive and grow. While the age-old centers of Arabic-speaking Jewry declined, Jews in Canada, South Africa, Australia, and Argentina transformed themselves from largely immigrant societies into more settled communities that sought to preserve their Jewish roots as they gained acceptance and cultural prominence in their new homes.

Despite obvious differences among these changing diasporas, their Jewish experiences reflected certain points in common. Unlike the battered Jewish communities of Europe, many Jews here were recent arrivals. Especially in South Africa and Argentina, many of the first Jewish immigrants settled on lonely frontiers in the pampas or the veldt. Unlike American Jewry, Jews in these changing diasporas lived not in a “melting pot” but in the middle of wider ethnic rivalries that in turn fostered, rather than discouraged, cultural diversity.

Non-Jewish ethnic rivalries—between French and English speakers in Canada, English and Afrikaans speakers in South Africa—fostered stronger Jewish identities in both societies. But unlike Canada, South African Jews had to deal with the moral dilemmas of apartheid. Like their Canadian cousins, South African Jews enjoyed a degree of acceptance that had eluded them before the war, especially from the Afrikaners. But that acceptance came at a high moral price that had a major impact on South African Jewish culture and politics.

It was in the postwar period that Jewish writers of the changing diasporas of Argentina, Canada, South Africa, and Australia began to play a visible role as cultural figures and interpreters of the Jewish experience. Almost invariably the children of Yiddish-, Ladino-, or Arabic-speaking immigrants, their parents had all lived on their own “Lower East Side”: the Jewish colonies on the pampas, the lonely peddler life in the South African veldt, the grim adjustment to the slums of Montreal, Buenos Aires, or Johannesburg. Jews settled even in the most remote frontiers. Yaacov Hasson’s “Iquitos: The Jewish Soul in the Amazon, Notes of a Voyager” evokes the tenacity of Jewish identity—and the impact of Zionism—even in the middle of the Amazon rain forest.

But after the war, these communities redefined themselves as they sought out different ways of becoming Argentines or Canadians while remaining Jews deeply concerned with their own history, with the legacy of the Holocaust, and with the security of the new Jewish state. Life writing especially captured the challenges and the poignancy of putting down markers in unknown and uncharted territory. Like David Daiches’s description of Scottish Jewry, this life writing in the changing diasporas highlighted how Jews sought to preserve their identity within non-Jewish cultures that were themselves, in places like Canada and South Africa, often defined by dueling narratives and sharp cultural differences.

Jewish Culture in Postwar North America

Larry Zolf’s “Boil Me No Melting Pots, Dream Me No Dreams” and Mordecai Richler’s memoir of hardscrabble Jewish neighborhoods in Montreal highlight real differences between Jewish Canada and Jewish America. Canadian Jewish identity was forged in a society that valued cultural pluralism and eschewed the ideal of the melting pot, where Jews had to maneuver between larger, competing communities. A generation closer to the “old home,” Canadian Jews were less likely than their American cousins to intermarry or to live in non-Jewish neighborhoods. It was during these years that Canadian Jewry began to become an integral but distinct part of a Canadian society that was itself struggling to define its identity in the face of rising nationalism in Quebec.

Montreal’s A. M. Klein, sensitive to cultural difference and linguistic nuance, wrote with equal empathy about the Holocaust, the formation of the Jewish state, and the French-Canadian culture that shaped his surroundings. His 1951 novella The Second Scroll is a profound gloss on the modern Jewish experience: the Holocaust, flirtations with communism, the rebirth of Jewish sovereignty, and the Hebrew language, all strikingly conveyed. Klein’s very sensitivity to the critical place of cultural difference and linguistic nuance enabled him to write powerful poetry about another people struggling to protect its identity, his French Canadian neighbors. Klein became an important influence on his fellow Montrealer, the songwriter and poet Leonard Cohen. It was not by coincidence that when Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau addressed a gathering of Canadian Jews in 1970, he told them that the “Jewish community also afforded Canadians a model in miniature of what Canadian society could and should be.”1 The next year, the Canadian government officially endorsed a vision of multiculturalism that encouraged different minority groups to protect and advance their own cultures.

Jewish Culture in Postwar South Africa

South African Jewry took root in an environment that encouraged Jewish difference rather than assimilation. Chaim Sacks’s “Sweets from Sixpence” evokes the challenges faced by Lithuanian Jewish immigrants on a new continent, as well as their ongoing struggle to find a niche in a land beset by conflict and tension between Afrikaners, English-speaking whites, Black Africans, and millions of “coloreds.” These years were a defining time for South African Jewry, as surging Afrikaner nationalists shut down Jewish immigration from Europe by the late 1930s, flirted with Nazi-inspired antisemitism, and finally gained political power in 1948. The political ascendancy of Afrikaner nationalists, marked by the growth of legally sanctioned apartheid after 1948, confronted Jews with a tough dilemma. On the one hand, Afrikaner antisemitism declined as the new government dismantled barriers to Jewish immigration and offered Jews the enormous material and social privileges connected with being white in an apartheid state.

On the other hand, those privileges came at a deep moral price. How could Jews profit from and sanction apartheid? Yet what choices did they have? The bitter 1957 exchange between Dan Jacobson and Ronald Segal on how Jews should react to apartheid also spoke to deeper issues, such as how Jewish minorities should navigate the fraught space between moral integrity and self-preservation.

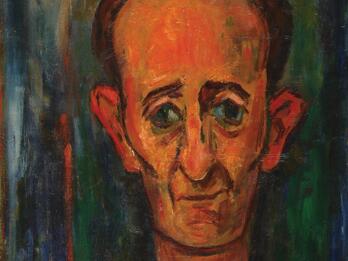

Despite these painful conflicts, which impelled many Jews to leave the country, the South African Jewish community stood out for its major contributions to South African culture: Lippy Lifschitz, Moses Kottler, and Irma Stern in painting and sculpture; Dan Jacobson, Sara Millin, and Nadine Gordimer in literature; Olga Kirsch in poetry. Olga Kirsch herself offers a striking example of how South African Jews moved in the uncertain and creative spaces that marked the boundaries of different cultures. Kirsch was born in a small town on the Orange Free State, wrote her poetry in Afrikaans, and emigrated to Israel in 1948. She spoke English with her husband and Hebrew with her children. As Andries Wessels points out, key themes in her poetry appealed simultaneously to both Zionist Jews and to Afrikaners:

Yet the silent longing remains unstilled

O land, o rest yet unfulfilled.2

Jewish Culture in Postwar South America

During the postwar years, Latin American Jewish literature in Spanish came into its own, especially in Argentina. As in Canada and South Africa, writers who had grown up in Yiddish-speaking immigrant homes published journalism, poetry, and fiction that reflected the promise and pitfalls of new frontiers and wide horizons. In Argentina, a major center of postwar Yiddish culture, second-generation Spanish-language writers, including Lázaro Liacho, Samuel Glusberg, Samuel Eichelbaum, Bernardo Verbitsky, and David Viñas, took their place alongside already-established Argentinian Jewish writers such as César Tiempo and Alberto Gerchunoff. Some, like Gerchunoff and Verbitsky, would leave their mark on Argentine culture not only as creative writers but also as leading journalists.

In these formative postwar years, Jews in Latin America did not cultivate rabbinic leadership, foster theological debate, or advance Judaic scholarship. But the land where Jorge Luis Borges and magic realism were born did inspire a wide and eclectic array of Jewish writing, a literature only one step removed from the shtetl but already inhabiting what Isaac Goldemberg called the seven circles of Jewish hell. Here, Marx rubs shoulders with Jeremiah, Jesus with Freud, and Kafka—Borges’s favorite writer—“laughs like crazy.” Heretofore marginalized, these plays, novels, short stories, poems, and memoirs from across the Latin American continent join the transnational Jewish conversation for the first time.

In Argentina, one writer in particular—Alberto Gerchunoff—symbolized the promise of Jewish integration into Argentine society. But after World War II, Gerchunoff himself tempered his optimism in the face of a new generation of Jewish writers who explored the limits of assimilation for an urbanizing and acculturating Jewish community. During this period, Argentina continued to be a major center of Yiddish culture and publishing. But for the first time in centuries, Spanish again emerged as a significant vehicle of Jewish cultural creativity in a nation that both embraced its Jewish minority and reminded them that on a basic level—reinforced by religion—they would always remain “different.”

Today Gerchunoff is justly celebrated for his 1910 collection of short stories entitled Jewish Gauchos, devoted to the Yiddish-speaking Jewish pioneers from Russia who settled in the new farming colonies of the pampas. These stories, called by one critic the “urtext of Latin American Jewish literature,” were also a paean to Argentina, an expression of Gerchunoff’s heady optimism about a Jewish future in this new country. Gerchunoff offered a template for Jewish integration into Argentine society and into the Argentine Spanish culture, especially attractive because of a centuries-old bond that linked Jews to the Spanish language. Indeed, the writer Bernardo Verbitzky would say that it was through Jewish Gauchos that “Argentine Jews acquired their citizenship papers.”3

But his 1945 essay on newsreels of the Nazi camps shows a Gerchunoff who is much more eager to assert his Jewish identity and to temper his earlier optimism about a Jewish future in Argentina. Like other Argentine Jewish writers, Gerchunoff was profoundly affected by the Holocaust and by Zionism. The decades that followed Jewish Gauchos saw not only accelerated Jewish immigration and urbanization but also growing antisemitism and a new awareness of the stubborn “Otherness” of Jews making their way in a Catholic country. This “otherness” reverberated in César Tiempo’s cycle of Sabbath poems, and to a certain degree in the fiction of Bernardo Verbitsky and David Viñas. Over time, it was both tested and nurtured by the populism of Juan Perón, the left-wing radicalism that attracted many young Jews, and the crisis caused by Israel’s kidnapping of Adolf Eichmann in 1960.

Notes

Harold Troper, The Defining Decade: Identity, Politics, and the Canadian Jewish Community in the 1960s (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010), 288.

Andries Wessels, “The Outsider as Insider: The Jewish Afrikaans Poetry of Olga Kirsch,” Prooftexts 29 (2009): 63–85.

Leonardo Senkman, “Argentine Culture and Jewish Identity,” in The Jewish Presence in Latin America, ed. Judith Elkin and Gilbert Merkx (London: Allen & Unwin, 1988), 255–70, 258.