Early Modern Italy: Where East and West Meet

Ashkenazim, Sephardim, and Marranos encountered each other in Italian cities, developing community structures that later influenced Jewish communal organization throughout the western world.

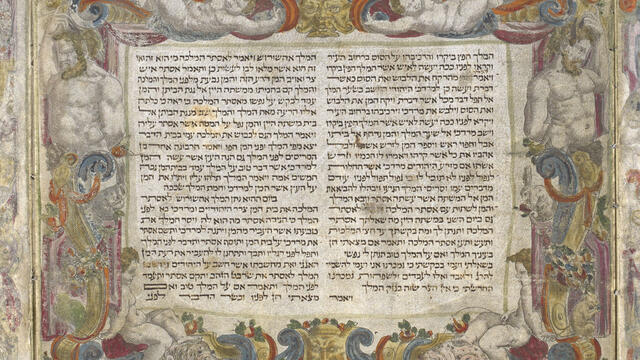

Italy, split into various states and regimes, attracted diverse Jewish migrants in the early modern period. In the Papal States, the pope ruled as a kind of secular governor. Ashkenazim and Sephardim encountered one another in Italy after the expulsion of the Jews from the Iberian Peninsula. Even later on, the Jews of Italy retained a connection with a variety of Jewish traditions, using several languages, including Hebrew, Yiddish, Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese.

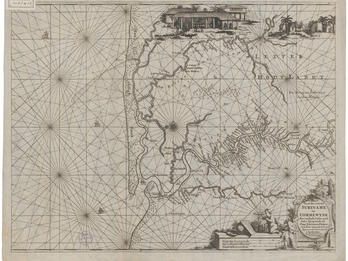

However, not every Italian ruler showed an interest in absorbing Jewish immigrants. For example, the Republic of Genoa did not even permit the presence of Jews until the end of the sixteenth century, and the Duchy of Milan did not allow Jews to settle there until the beginning of the modern period. The attitude of Venice’s leaders on this matter fluctuated. Until 1509, the city’s governors did not permit a Jewish presence in the city itself. But in that year, in the wake of the Venetian war against the League of Cambrai, a stream of Jewish refugees arrived from settlements that were part of the far-flung Venetian maritime empire, and the Venetians permitted them to remain in the city after the war was over. In the 1530s, Jewish immigrants began to flow into Italy. These included “Levantine” Jews, who came from the eastern Mediterranean and were in fact Ottoman subjects. Most of them were descended from Sephardim who a generation earlier had moved to the Ottoman Empire, where they found a safe haven after the expulsions from Spain. However, after the establishment of the Inquisition in Portugal in 1536, Portuguese Marranos began to slip out of the country. Some who fled directly to Italy returned openly to Judaism. Others, even once in Italy, continued to behave as Catholics but still sought to approach the Jewish communities as much as they could without incurring the danger of being brought before the Papal Inquisition.

The rulers of the Italian states found themselves in an awkward position. On the one hand, from the Catholic Church’s point of view, the Marranos who returned to Judaism were Catholic heretics. On the other hand, not all Christian scholars agreed that the mass forced baptism of the Jews of Portugal in 1497 had, in fact, been legal. Some maintained, for example, that forced baptism was inherently invalid. This was the opinion of Pope Clement VII (1478–1534), who agreed to accept Portuguese Marranos in Ancona, a port city within the Papal States, in hopes that they would help develop the economy there. His attitude later influenced secular rulers of Italian cities and states. The rulers of Ferrara, of Tuscany, and, later, Venice began to allow the entry of Jews into their domains.

In 1550, the Venetian Republic renewed the law requiring the expulsion of Marranos to accommodate Venetian merchants, who were apprehensive about potential economic competition. Around this time, anti-Jewish papal policies reached a peak. In 1553, the Talmud was burned, first in Rome and then in Bologna, Venice, and other cities. Twenty-five Jews were burned at the stake in Ancona.

The first ghetto, established in 1516, was located in Venice and remained in existence until the conquest of the city by Napoleon in 1797. Another ghetto, which expanded and contracted over the years at the request of the Jewish population, was established in Rome in 1555. Eventually all Jews in Italy were required to live in ghettos, although it took over a century for this policy to be fully implemented. Jewish quarters, which were simply areas (sometimes fortified) within cities and towns where the Jewish community lived, had been a common sight in medieval Europe, but the ghetto was distinctive in that Jews were required to live within it. Similar enclosed or defined areas could be found in early modern Poland and Germany as well, such as the Judengasse (Jews’ Street) of Frankfurt, instituted in 1462.

Near the end of the sixteenth century, an economic recession in the Ottoman Empire drove more Levantine immigrants toward Italy. At the time, Italy appeared to be the only Western country where it was permitted to practice the Jewish religion openly, attracting more Marranos. In 1589, the Venetian Republic issued a document defining the conditions for residence for the “Ponentini,” one of two separate groups of Jewish immigrants. The Ebrei Levantini e viandanti (Levantine and Wandering Jews) were, as noted earlier, former subjects of the Ottoman Empire, while the Ponentini (Western) were descended from the Marranos. The differentiation of these two groups of Jews, both primarily of Sephardic descent but who had followed different historical paths, exerted an enormous influence on Western European Jewry and even beyond.

Throughout most of Europe, including Italy, Jews had often worked as pawnbrokers and were thus sometimes perceived negatively as usurers. This pejorative term, however, was chiefly used by church officials and was not representative of how Jewish pawnbrokers were regarded by Christian society in general. In addition, this negative stereotype was belied by the reality that the Ponentini mainly engaged in international commerce and financial activity connected with that commerce. They were generally economically, if not socially, integrated into the fabric of their places of residence.

The first Jews to establish synagogues in Venice were Ashkenazim: the Scuola Grande Tedesca dates to 1528, the Scuola Canton to 1532, and the Scuola Italiana, to no later than 1575; three smaller synagogues were the Scuola Coanim (1587), the Scuola Luzzato (sixteenth century), and Scuola Meshullamim (no later than 1635). Sephardic synagogues—such as the Scuola Ponentina and the Scuola Levantin—were established only toward the end of the sixteenth century, but they were often magnificent, probably constructed by Christian architects hired for their expertise in building churches. One of these, Baldassar Longhena, known for his splendid Venetian churches, probably designed the Spanish Scuola.

The Sephardic Jews in Italy played a central role in forming the identity of the Sephardic diaspora in general and particularly in the West. Sephardic communities in Western Europe and the New World adopted communal patterns that developed in Venice at the end of the sixteenth century. For example, the organization of the Sephardic communities of Amsterdam, Hamburg, London, and others in the West was based on bylaws drafted for the first time in Venice. Also, the various charity confraternities were modeled after patterns first established by the Ponentini in Italy.