Community, Congregation, and Self-Government

The early modern period witnessed flourishing Jewish self-governance across the diaspora, as economic utility to host nations enabled unprecedented communal autonomy.

The Posen Library contains many sources drawn from the official regulations of Jewish communities, communal bodies, confraternities, and associations. All these institutions shaped the autonomous organization of the Jews in the diaspora. Moreover, the reader of this section will also find halakhic rulings and responses to queries that relate to the self-government of communities throughout the diaspora. In the early modern period, several national governments saw an economic benefit in tolerating the presence of Jewish communities within their territories; the result was that this period offers exceptionally fascinating examples of the self-rule of Jewish communities.

During the early modern period, a series of territorial councils arose, and these served as umbrella organizations for the Jewish communities in a given country: the Council of Four Lands in Poland, the Council of the Land of Lithuania, and the Council of the Land of Moravia. This section also presents the resolutions passed by the assembly of the Italian communities, which took place in Ferrara in 1554, and the Synod of the Jewish communities of Germany, which met in Frankfurt in 1603.

Jewish autonomy flourished in the Ottoman Empire to a degree unprecedented elsewhere. Although their population fluctuated over the centuries, both Istanbul and Salonika had enormous Jewish communities. In certain periods, the cities were home to tens of thousands of Jews. The many Jewish congregations in those cities included both Romaniote (Greek-speaking local Jews) and, after 1492, a variety of exiles from different areas in Spain and Portugal.

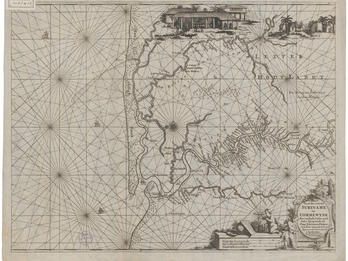

Between the end of the sixteenth and the beginning of the eighteenth centuries in Western Europe and the New World, Sephardic congregations were established by conversos or New Christians who were returning to the Jewish religion. These congregations were much smaller than those in the Ottoman Empire, but they became vibrant and wealthy centers with extensive commercial networks. In Amsterdam, Livorno, Hamburg, and London, and later in Bayonne and Bordeaux, until the 1720s, former New Christians were reabsorbed into Jewish communal life. These Sephardic Jews established daughter congregations in the Dutch and English colonies in the Americas. Each congregation took on a form of government and administration based, in general, on the Venetian Ponentine (a term for former New Christians) congregation.

Despite the activities of impressive rabbinic figures throughout the early modern period, rabbis complained that they were losing their power and influence against the rising power of the parnasim (notables), who ruled their communities with a high hand. At the same time, the role of the rabbi became increasingly professionalized.

In Central Europe, especially in Germany, an elite of Court Jews arose. They counted in their ranks bankers and entrepreneurs, army contractors, and international merchants, all of whom provided for the financial needs of the absolutist rulers. In return for their services, they gained special privileges and a social status denied to ordinary Jews, with access to the ruler’s court. In some cases they fell victim to plots in the royal courts and to anti-Jewish attitudes, as in the famous and tragic story of Joseph Süss Oppenheimer (1699–1738). From a family of Court Jews, Oppenheimer became economic adviser to the Duke of Württemberg, but after the duke’s death, he lost favor, was imprisoned, and was finally executed. The Posen Library includes a number of entries focused on these elite Jews, including images—paintings, engravings, ketubot (marriage contracts), and so on—that illuminate the lives and experiences of the upper classes of Jews, and in particular of the so-called Court Jews.

Related Primary Sources

Primary Source

Takkanot (Regulations)

- Printers shall not be permitted to…

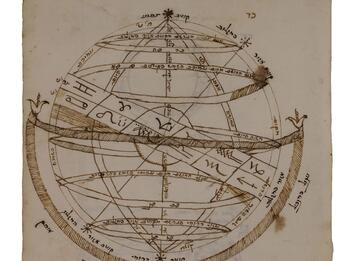

![M10 622 Manuscript, probably from Ukraine]. Manuscript probably from Ukraine, c. 1740 with a broad collection of practical kabbalah and mystical magic. Facing page manuscript arranged vertically with Hebrew text in the shape of a figure wielding two long objects.](/system/files/styles/entry_card_sm_1x/private/images/vol05/Posen5_blackandwhite166_color.jpg?h=cec7b3c9&itok=Sz6u21MQ)