Early Modern Spiritual Ideologies

Early modern Jewish spiritual life encompassed diverse elements, including theology, ethics, liturgy, and messianism.

Ethical Treatises

Jewish ethical treatises belong to a tradition going back to the talmudic era. While rabbinic literature contains a vast wealth of ethical material embedded in it, one tractate of the Mishnah, called <a href=”4e833466-146f-4304-82c3-baad66621988” ref-type="entry">Pirke Avot (Chapters of the Fathers)</a>, is considered to be devoted to that subject. In the medieval period, commentaries on that tractate were written, as well as more systematic works, which also drew on late-antique oral traditions and Greco-Arabic philosophical systems. From the exceptionally rich reservoir of early modern ethical literature, we have chosen works written by Jews from the Ottoman Empire, Western Sephardim, former New Christians, and others.

Sermons

During this period, the sermon became an important and influential genre. Certainly late-antique and medieval rabbinic scholars gave derashot (homilies), but only a few of these have survived. Sermons—given orally on Jewish holidays, or on the occasion of important public events, or in the form of eulogies for well-known figures—though still mostly ephemeral performances, began to be written down more systematically, compiled, and edited (sometimes extensively). The printing press enabled these to be distributed in print form far beyond their original locale. Some preachers were delivering sermons in the vernacular, with audiences that included non-Jews—Leone Modena perhaps being the most famous of these. Sermons are an especially rich genre, as their authors are responding directly to the most immediate concerns of the local Jewish community and using the concepts and teachings they think will resonate most with their audience.

Devotional Literature

The next part of this section, devotional literature, is composed of works primarily written by women, such as the prayers by Toybe Pan of Prague, in Yiddish, and Brites Henriques, the Crypto-Jew, in Portuguese. These texts, though few, speak eloquently of a side of Jewish life—female spirituality—that was never before available to historians.

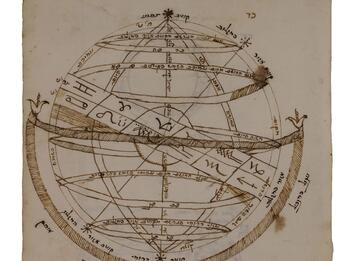

Kabbalah

In contrast, the new trends in kabbalah that characterized this period are expressed in an extensive and rich section. Here readers will find texts by kabbalists exiled from Spain who fled to Italy and the Ottoman Empire, such as Judah Ḥayyat and Joseph Taitatsak; others by famous figures from the kabbalist center in Safed, such as Moses Cordovero, Isaac Luria, and Ḥayim Vital; and great kabbalist scholars from Italy, such as Menaḥem Azariah da Fano, and from Central and Eastern Europe. Critiques of kabbalah appear here as well, notably Leone Modena’s Ari nohem (Roaring Lion), published in Venice in 1638.

Messianism and the Sabbatean Movement

As for messianism, many Jews were attracted to various radical movements in the period between the expulsion from Spain and the middle of the eighteenth century. In the early sixteenth century, rumors abounded about the ten lost tribes and their kingdom beyond the Sambatyon River. The appearance of David ha-Reuveni and the activities of Solomon Molkho breathed new hope into the hearts of many believers. The Jewish messianic fervor reached a peak in the 1660s, with the appearance of Shabbetai Tzvi, a messianic figure from Izmir (Smyrna). Within a short time, the news of the messiah’s advent reached the entire Jewish world. The letters of Nathan of Gaza, the brilliant prophet and theoretician of this movement, fired the imagination of Jews throughout the diaspora. After Shabbetai Tzvi’s conversion to Islam, however, most of his believers abandoned him. Some nevertheless remained faithful to the messianic hopes that he had kindled, and covert communities of believers remained active, including those who followed in his footsteps and became Muslims, convinced that redemption had commenced.

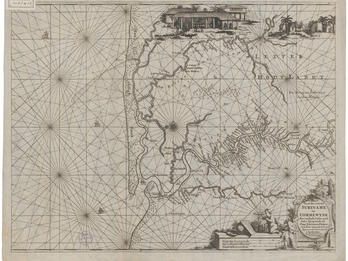

Attitudes toward the Land of Israel

Sources from this period display the many ways Jews living in and outside of the land of Israel related to its distinct place in the Jewish tradition. The Ottoman Empire ruled the area from the time of its defeat of the Mamluks in 1516. A small Jewish community lived in Jerusalem, supported by charitable donations, and Safed was a flourishing center of Jewish learning and kabbalistic innovation. During the sixteenth century, the textile industry became important to the economy, especially in Safed, but also in Jerusalem and Nablus. In this section are excerpts from sermons, letters written by travelers to Jerusalem recounting their experiences, halakhic texts that involve issues related to those particular commandments to be observed by Jews living in the land of Israel, accounts of the economic situation in Jerusalem meant for the emissaries who were charged with raising money from Jewish communities around the world for support of the Jews living there, and more.

Related Primary Sources

Primary Source

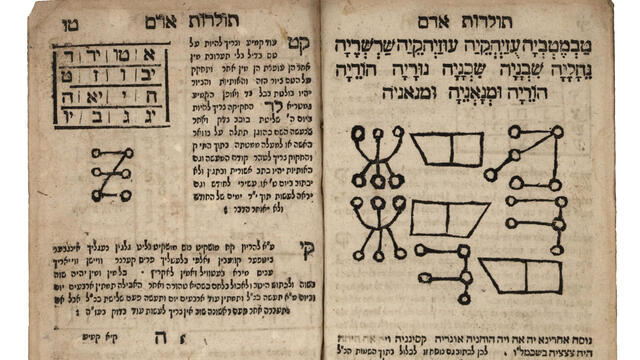

Me’ah she‘arim (A Hundred Gates)

Primary Source

Tomer Devorah (The Palm Tree of Deborah)

- The quality of humility includes all qualities…