Class 4: Sephardic Women’s Food Stories: Bridging Past and Present through Taste

Sephardic women have used food, recipes, and storytelling to bridge past and present—from Lady Montefiore’s 1846 cookbook to Claudia Roden’s current legacy.

Food, Gender, and Storytelling in Sephardic Jewish Culture

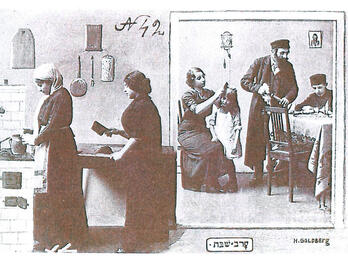

Food and women’s roles have long been bound together in Jewish and other histories, and Class 4 highlights this nexus as it gives center stage to the significant role of food in Sephardic culture. This session investigates cookbooks, fiction, interviews, and scholarship that explore food preparation, presentation, and consumption alongside food stories, thus bridging the past and the present.

Lady Judith Montefiore was the wife of Sir Moses Montefiore, a notable British Jew of Italian Sephardic origin. She was known as the “First Lady of Anglo-Jewry” and, in 1846, she identified the absence of works of “culinary science” for those devoted to the “Hebrew kitchen.” To rectify this problem, she transformed domestic labor into an opportunity for cultural transmission by publishing the premiere Anglo-Jewish cookbook: The Jewish Manual, by “A Lady.” In this book, Montefiore not only offers recipes for mock turtle soup and brown cucumber sauce but also instructs women—the intended audience—in methods for keeping one’s hands soft and fingernails supple, a reminder that culinary practice was never merely about sustenance, but was also part of the cultivation of accepted modes of femininity.

How Sephardic Flavors Shaped Israeli and Global Jewish Identity

We will also delve into Claudia Roden’s The Book of Jewish Food, in which memoir is intimately bound up with food, as well as a short, turn-of-the-twentieth-century Tunisian cookbook, which offers few instructions for preparing its dishes, including more than twenty kinds of “tajin.” We can see how food from Middle Eastern and North African Jewish communities became integral to Israeli, and to a large degree “Jewish,” food. These changes did not necessarily occur as a result of assimilation of these communities. As scholar Noam Sienna notes, the Tunisian Jews who brought shakshuka to Israel when they immigrated to Israel in the 1950s might have faced discrimination, but their food was eventually “valorized as contributing to the harmonious mosaic of new Israeli ethnicity and validating the emerging sense of locally rooted Levantine identity.”

We will also investigate the expectations of Sephardic women through their kitchen stories. Corie Adjmi’s novel The Marriage Box, for example, exposes the requirements of Syrian Jewish women and the notion of shatra, praise for a woman who cooks and serves beautifully and abundantly, even in late twentieth-century America at a Thanksgiving dinner, where ham is the main course. An interview with American women writers also reveals a surprising demand of the publishing industry: that Sephardic women write about food and also include recipes in their books.

In the spirit of “cooking-as-inquiry,” this session ideally should include, if not cooking itself, a direct engagement with food to experience this important aspect of Sephardic culture across all five senses. Activities could include participating in a cooking session using Roden’s recipes, watching a cooking demonstration, or taking a trip to a Middle Eastern restaurant or food shop.

Discussion Questions

Is cooking Sephardic food if you are not Sephardic a form of cultural appropriation?

Discuss culinary expectations in Sephardic culture in relation to the ways gender is presented in these sources. How is food tied up with other gender norms?

Why do you think Middle Eastern and North African Jewish food has become so popular? In the United States, for example, has it replaced the deli as offering quintessential Jewish food?