Class 1: Jews and Muslims from Early Islam to the Ottoman Age

Discover how Jews lived, traded, and thrived under Islamic empires, from the rise of Islam to Ottoman and Safavid rule across the Middle East and North Africa.

The Rise of Islam and Dhimmi Status

Islam emerged in seventh-century Arabia after a figure known as Muḥammad proclaimed himself the final messenger of the same God (Allah in Arabic) worshipped by Jews and Christians. This new religion framed itself as superseding, or taking the place of, Judaism and Christianity. Islam sought converts among these religions as Mohammed and his successors, known as caliphs, rapidly captured territory, first in Arabia, then throughout the Middle East and North Africa and even into modern Spain, Portugal, and southern Italy. In most places, the Arab invaders did not force Islam on Jews and Christians, and thus in many of these lands, a Muslim minority governed over substantial Christian and Jewish populations. Islamic law mandated tolerance for Jews and Christians, who were considered “protected” (dhimmi) populations, but tolerance did not mean political equality. Dhimmi populations had to pay a special tax (jizya) and faced many restrictions, prompting some Christians and Jews to convert. Yet policies were enforced differently across time and place, and some Jews were able to achieve economic prosperity and even occasionally political influence in Islamic contexts. Overall, Jewish life under Islamic rule was more stable than in Christian realms, where tolerance was not mandated, and expulsion was more frequent.

Jewish Communities in the Ottoman and Safavid Empires

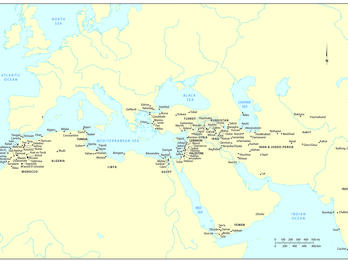

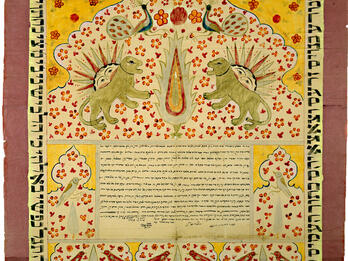

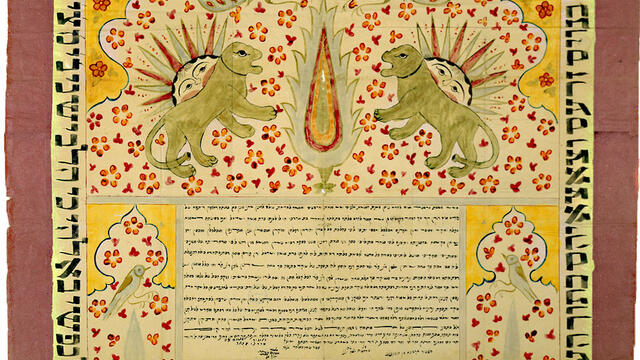

From their emergence in the seventh century and into the twentieth century, Islamic empires were often stronger and more prosperous than their Christian European counterparts. The most important early modern Islamic power, the Ottoman Empire (1299–1922), controlled most of southeastern Europe for centuries, along with much of the Middle East and North Africa. The Ottoman Empire’s capital, Constantinople (known today as Istanbul), was at the edge of Europe, and its leaders welcomed a large influx of Jews who were expelled by Christian monarchies of Spain and Portugal after their conquest of the Arab-controlled part of Iberia (al-Andalus). These exiles, known as Sephardic (“Spanish”) Jews, often retained many of their religious and cultural traditions, including the language Ladino (Judeo-Spanish). Many, though not all, of the Jewish communities on the Mediterranean coastline seen in this map included Jews of Iberian origin. To the east, a notable Jewish minority lived in Iran, known as the Safavid Empire (1501–1736), often referred to in the West as Persia. This longstanding Jewish community shared local cultural symbols with other Iranians and even adopted national symbols into their religious documents, as in this ketubah from Isfahan. These various Islamic governments and their Muslim subjects sometimes persecuted their Jewish minorities, as seen in this report on the community of Isfahan. However, Safavid Iran, which subscribed to the minority Shia Islamic tradition, directed far more violence against Sunni Muslims, and the Ottoman Empire did much more harm to Shia Muslims and, in its final decades, to Christian minorities.

The Ottoman Empire and other Islamic powers faced encroachment from European powers from the eighteenth century onward, culminating in military takeover. This began with a brief French invasion of Egypt (1798–1801) and included a long French occupation of Algeria beginning in 1830 and de facto British control over Egypt after 1882. In all of these contexts, Jews had to balance influence from Western European Jewish communities with local loyalties and cultural ties, as seen in this appeal to open a Jewish girls’ school in Istanbul. Yet the Ottoman Empire would survive until soon after its loss in World War I, and Jewish communities lived throughout its regions, including modern Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon. The region known to many as Palestine, and to Jews as the land of Israel, came under Ottoman control in 1516 and included a small Jewish minority among its largely Muslim, Arabic-speaking population.

Zionism, a national movement that advocated for Jewish cultural rebirth or sovereignty in the biblical Land of Israel, created new questions for Jews in the Ottoman Empire. For some Ottoman Jews, Zionism was at odds with their loyalties to the empire. But others, including some Ashkenazic Jews who had already settled in the area, viewed support for Ottoman rule and Zionism as potentially compatible, as seen in Eliezer Ben-Yehuda’s article urging Jews to embrace and prepare for service in the Ottoman military.

For most MENA Jews, however, questions related to Zionism had little practical impact prior to World War I. Of far greater importance was the role of European colonial powers such as France and Britain, in both the geopolitical and cultural realms.

Discussion Questions

What regions had substantial Jewish communities during this period? Does this map aid in your understanding of any of the sources, or the relationship between them?

What do these sources reveal about Jewish life in Islamic contexts during this period? Consider factors such as the role of traditional Judaism, relations with Muslims and Christians, interactions wit

Imagine yourself to be a Jewish community leader who would like to establish a school in a MENA locale. What questions might you face about the nature of the school (language, content, admissions)? Ho

In trying to establish such a school, what obstacles might you face from state and local officials or from others in the Jewish community? Where might you look for support and resources?