Jewish Printing and Book Culture

Jewish printing unified far-flung communities by standardizing religious texts, created textual uniformity, and enabled vernacular translations, and facilitated the spread of Jewish texts and knowledge.

Printing, which Jews adopted immediately after its invention, helped to unify far-flung communities. Where previously Jewish learning had been transmitted through the individual copying of manuscripts, the nascent printing industry now made Jewish books widely available. It also, inevitably, led to unprecedented uniformity in fundamental Jewish texts. Printing became widespread in the West in the middle of the fifteenth century. Books in Hebrew type were first printed in Rome (1469) and were soon being produced elsewhere in Italy and even in pre-expulsion Spain. After the 1492 expulsion, Jews fleeing Spain for North Africa and the eastern Mediterranean brought the new technology with them. Printers, many of them Christian, in Venice, Istanbul, Amsterdam, and elsewhere thus played a decisive role in the formation of an interconnected and unified Jewish culture. These printers—and the new audiences for their products—reshaped the face of Jewish culture in various, complex ways.

Printers and Patrons

In the sixteenth century, Jewish printing houses proliferated; perhaps the most famous was the Soncino press in northern Italy, which printed the first Hebrew Bible with vocalization. Among Christian-run houses that produced books in Hebrew type was the Bomberg press in Venice, which produced the first complete edition of the Babylonian Talmud, between 1520 and 1523. Both types of houses employed Jews—including some women—and non-Jews as editors, proofreaders, typesetters, and more. In the process, the presses became fertile points of contact not only for Ashkenazic and Sephardic Jews—Sephardic printers in Amsterdam also published Yiddish books curated by Ashkenazic proofreaders, for instance—but also between learned Jews and their Christian colleagues.

Money to cover printing costs was raised by both authors and printers, with the resultant volumes being dedicated to their Jewish or non-Jewish patrons. One such patron, Doña Gracia Nasi (ca. 1510–1569), supported the production of the so-called Ferrara Bible, a Spanish translation of the Hebrew Bible that came out in 1553. Her daughter Doña Reina Mendes, in 1593, established a printing press in Belvedere (her residence near Constantinople) and printed several works there toward the end of the sixteenth century.

The Printing of Religious Literature

Most famously, Daniel Bomberg, a Christian printer from Antwerp, established a printing house in Venice in 1516. Employing Jewish proofreaders, he printed two editions of the Hebrew Bible with the principal commentators (known as Mikra’ot gedolot) between 1516 and 1526. Even farther-reaching in its consequences was Bomberg’s printing of the Babylonian Talmud, with the commentaries of Rashi and Tosafot, providing a uniform model of the Babylonian Talmud that was eventually adopted by the entire Jewish diaspora. The first edition, published between 1520 and 1523, comprised forty-four tractates; in later years, Bomberg printed three more editions, all of which were either partial or incomplete. Bomberg established the now-standard layout of the page of the Talmud for the first time.

The Shulḥan ‘arukh (Set Table), a halakhic code written by a Sephardic rabbi, Joseph Karo, and printed for the first time in Venice in 1565 (in two volumes), was reprinted just a few years later in Kraków; this time, it included the glosses of the Ashkenazic scholar Moses Isserles (1530–1572; the “Rema”), known as the Mapah (Tablecloth), representing a summation of Ashkenazic practices. In this way, within (and on) the pages of what would soon become the most important and popular halakhic work of the time, the Sephardic and Ashkenazic traditions encountered each other. This book came to be regarded as the supreme halakhic authority, by both erudite scholars and by ordinary readers, Sephardim and Ashkenazim, throughout the diaspora: in the Ottoman Empire and North Africa, in Italy and Northern Europe, in the Land of Israel and Eastern Europe.

Not only halakhic practice, but prayer liturgies too began to be standardized. Although the text of the Hebrew Bible had long been set, so too a standard set of commentaries became attached to it, shaping the “rabbinic Bible.” The availability of the biblical text encouraged a wider range of biblical scholarship, and new genres arose while others declined in popularity.

The Early Modern Jewish Bookshelf

The printing revolution had far-reaching consequences for the dissemination of Jewish works and Jewish knowledge. In the early modern period, a number of institutional Jewish libraries arose, one of the first and best organized of which was in the ‘Ets ḥayim Talmud Torah in the Sephardic community of Amsterdam. By 1680, after inspecting libraries in Poland, Germany, and Holland, Shabbetai Meshorer Bass composed the first Hebrew booklist or bibliography.

During this period, Jews were settled across a broad geographical area and spoke and wrote in numerous different languages. Works that had hitherto been known only in the original Hebrew were translated into various vernacular languages that had begun to be used for literary purposes: primarily the newly flourishing Ladino and Yiddish, but also Judeo-Persian, Portuguese, and Italian. Original works were composed in these languages as well, again mainly in Yiddish and Ladino. The first Jewish newspapers were published in Amsterdam: the Gazeta de Amsterdam, in Spanish, which began to appear in 1675, and Kuranten, in Yiddish, which came out in 1686/7. Three issues of an early form of a Hebrew periodical, established by Isaac Lampronti (1679–1756) and featuring halakhic discussions by Lampronti’s students, appeared in Ferrara in 1715.

All this activity enhanced an awareness among Ashkenazic Jews of what the scholar Avriel Bar Levav has called the consciousness of a “Jewish bookshelf.” It also sparked a rising sensitivity to the nature, scope, and educational merits of the knowledge being disseminated. With the formation of an increasing and expanding Ashkenazic readership, and the vigorous activity of Jewish printers who became cultural agents of the first order, some Jews felt the need to supervise the process of printing, which led in turn to the formation of community censorship.

In some cases, a book would come to include statements of approval (“approbations”) from prominent rabbis; in others, rabbis or communal councils would issue rulings on the permissibility or impermissibility of specific books. Because of the requirements of the Spanish Inquisitions, too, not only Jews but also former Jews might be involved in censoring both printed books and manuscripts; in addition, not a few authors self-censored their own books.

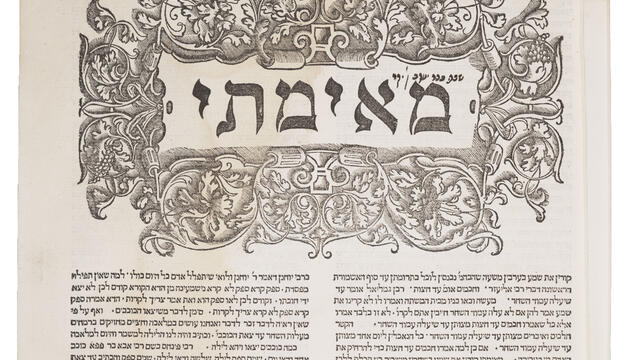

Illustrating the flourishing printing industry in its many different facets, the Posen Library presents an array of sources. Many are fascinating accounts of the efforts necessary to bring a book to press that appeared in the volumes themselves, such as dedications, printers’ forewords, authors’ introductions, and colophons, composed by the books’ authors, editors, and printers. In addition, there are texts that illuminate some of the communal controls exerted over the printing of books, such as the Inquisition’s list of rules for censoring Hebrew texts drawn up by the censor, a former Jew, or the approbations—or bans on scandalous books written up by Jewish communal and rabbinic authorities. Interspersed with these are images of the title pages and frontispieces of some of the books printed during this period. Here, too, users will find lists, both text and image, of volumes in individual libraries and in a yeshiva library, as well as some being offered for sale by the printer Menasseh Ben Israel and his son. Finally, we present a rich assortment of examples of some of the many languages in which Jews expressed themselves in print (and, occasionally, in manuscript) in this era.

![M10 622 Manuscript, probably from Ukraine]. Manuscript probably from Ukraine, c. 1740 with a broad collection of practical kabbalah and mystical magic. Facing page manuscript arranged vertically with Hebrew text in the shape of a figure wielding two long objects.](/system/files/styles/entry_card_sm_1x/private/images/vol05/Posen5_blackandwhite166_color.jpg?h=cec7b3c9&itok=Sz6u21MQ)