Class 1: Jewish Emancipation in Western Europe, 17th–19th Centuries

Trace the modern emancipation of Jews—from “Court Jews” to full citizens—in France, England, the Netherlands, and Germany.

Jews and Power before Emancipation: Hierarchies and Alliances

Before the advent of modern citizenship in the eighteenth century, political belonging in Christian Europe did not rest on universal rights. Instead, the legal position of individuals in medieval and premodern Europe depended on their membership in specific groups (or “corporate bodies”) such as towns, guilds, and churches. Exclusion from nearly all major corporate institutions left Jews in a particularly precarious legal position. Possessing markedly fewer legal protections and avenues for political inclusion than Jews living under many Islamic regimes, Jewish communities in Christian Europe faced discrimination as the religious “Other” and were largely barred from the existing systems of civic participation.

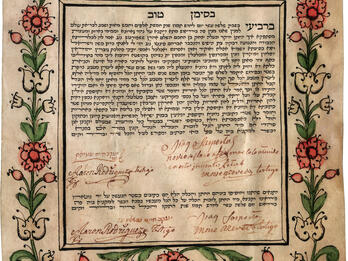

To secure protection, Jewish communities forged what historian Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi called “vertical alliances” with rulers. Monarchs offered their Jewish subjects—as collective communities—protection in exchange for economic and other services, such as loans. Mediated by influential yet vulnerable figures like seventeenth-century “Court Jews,” these privileges—granted via charters or letters patent—were constantly being renegotiated. These arrangements left Jewish communities doubly vulnerable, as is poignantly narrated in the memoirs of Glikl of Hameln, a German Jewish woman of the period. Rulers could withdraw their protection at will, and alliances with the governing authority often alienated Jews from their Christian neighbors.

In a system where Jewish rights relied on the benevolence of individual rulers, Jewish legal status varied widely. Depending on the location, medieval Jews faced restrictions on settlement, trade, property ownership, occupation, and religious practice. Heavy taxes strained daily life and reinforced internal hierarchies. From the late sixteenth century onward, some Jews gained broader civil rights. Attracted by their commercial expertise and ties to global trading networks, cities like Bordeaux, Amsterdam, Hamburg, and London, and European colonies in the Americas, welcomed Spanish and Portuguese “New Christians”—descendants of Jews forcibly converted to Christianity—whose return to Jewish identity and communal life they tolerated. In early seventeenth-century Amsterdam, for instance, Jewish merchants of Portuguese origin like Antonio (Isaac) Lopez Suasso enjoyed freedom of residence, property rights, and open worship; by the 1650s, they were formally recognized as full subjects of the Netherlands. Completed in 1675, the Great Synagogue of Amsterdam, then the world’s largest Jewish house of worship, symbolized their integration into the city’s fabric. Ashkenazic Jews, by contrast, remained legally and socially marginalized throughout the European continent.

Emancipation and the Birth of Modern Citizenship

Enlightenment ideas and the Atlantic revolutions of the late eighteenth century introduced new theories of government and a new conception of rights grounded in liberal principles—popular sovereignty, individual liberty, the rule of law, religious freedom—with profound implications for Jews. Emphasis on individual rights rather than on corporate belonging challenged privileges based on religion or economic role, raising questions such as: what role should religion play in state membership? How inclusive should citizenship be regarding race, class, and gender? Owing to the legal disabilities they had long suffered, and widespread negative perceptions of their religion and customs, Jews became a test case for defining the boundaries of national belonging amid the rise of modern nation-states and bureaucracies.

From the late eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth century, philosophers and theologians debated the merits of granting Jews full citizenship. Advocates called for not mere “toleration” but full “emancipation,” a term drawn from Roman law referring to the manumission of slaves or the liberation from paternal authority. Today, historians use emancipation to describe the process through which Jews gained civil and political rights. Spanning multiple decades, legal emancipation unfolded unevenly across Europe (for example, England, 1858; Austria-Hungary, 1867; Germany and Italy, 1870). France extended unconditional equality in 1791 following a petition from the Jewish communities of Paris, Alsace, and Lorraine. But in 1806, Napoleon presented the Jewish community with questions assessing their loyalty and integration, and the 1808 Napoleonic decrees curtailed Jewish rights, showing that emancipation was often contested and incomplete.

Jews were active agents in their emancipation, advocating tirelessly for inclusion based on their readiness to fulfill civic duties, such as military service. They countered stereotypes of disloyalty, greed, clannishness, and physical weakness while highlighting their social contributions, moral and religious “regeneration” (a term drawn from the debates over their desired status), and patriotism. They combined historical, moral, and philosophical arguments with practical demonstrations of fitness for citizenship.

Division Within: Competing Visions of Jewish Identity

The political struggle for rights, however, did not result in Jewish unity; rather, it drew on, and prompted, new divisions. Some Jews, such as the Sephardim of Bordeaux in France, worried that extending rights to France’s Ashkenazic communities might reduce their own status. Moreover, the shrinking and, in some places, outright abolition of Jewish communal autonomy prompted deep anxieties. Could Judaism, as both a religion and a shared sense of identity, endure if it were based entirely on voluntary participation? Access to individual rights thus led to competing visions of Jewish identity and the collective future of Jews. Reformers promoted a universalist vision of Judaism aimed at showing its compatibility with modern citizenship, provoking resistance from those committed to a collective identity rooted in Jewish law. These debates over religion, relationship to the state, and communal authority shaped denominations and subcultures that continue to influence intercommunal discourse, regarding matters such as intermarriage, women’s rights, and the definition of Jewish identity in Israel and the diaspora.

From Emancipation to Antisemitism: The Paradox of Progress

By the end of the nineteenth century, the removal of legal and social barriers between Jews and Christians across Europe profoundly transformed Jewish lives. Geographic mobility, access to secular education, the removal of occupational restrictions, and the ability to marry across religious lines, among other changes, paved the way for integration into broader society, as shown in the example of the actress Rachel Félix. Paradoxically, Jewish progress in rights and acculturation did not end prejudice but transformed it into a racial antisemitism that the Dreyfus Affair made impossible to ignore.

Discussion Questions

On what basis did some European Jews enjoy more legal, social, or economic rights than others in the premodern period (late 15th–late 18th century)? What factors might explain these differences?

How did European Jews advocate for greater rights and express their sense of belonging in the societies around them? What kinds of arguments did they make to support their cause?

Historian David Sorkin sees Jewish emancipation as a process, not a single event. Using two sources, explain this idea and why it matters for understanding citizenship and belonging.

Racial antisemitism in the 1880s was a backlash to expanding Jewish rights. What other minority groups have faced similar reactions seeking to restrict their gains?