Jewish Emancipation, Citizenship, and Belonging

Trace the evolution of Jewish citizenship from 18th-century France through Europe, the Ottoman Empire, and the Middle East, where debates over rights endure.

From Emancipation to Equality: The French Model

Did the granting of citizenship in eighteenth-century France require Jews to abandon their Jewish identity? If not, what—if any—compromises did they undertake to negotiate their national and communal belonging? For several decades, historians maintained that the promise of equality in France was realized only at the cost of Jews’ collective identity, citing as evidence the famous 1789 declaration of the Count of Clermont-Tonnerre—an advocate of Jewish emancipation—that “the Jews should be denied everything as a nation but granted everything as individuals.”

In recent decades, modern Jewish historians have offered an alternative understanding of French Jewish citizenship, one in which membership in the nation-state coexisted with forms of Jewish identification and loyalty. More important, they have drawn attention to the fact that the French model was only one path to citizenship for Jews in the modern era.

Different Views of Jewish Citizenship

Far from submitting to Clermont-Tonnerre’s view, Jews in Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East articulated multiple visions of the relationship between individual and collective rights. These various and often conflicting expressions of Jewish belonging were not envisioned as confined to a single region but were transnational in scope, particularly during the nineteenth century, as Jewish communities grew increasingly interconnected. These connections were facilitated by European colonial expansion, the growing power of print media, and increasing cross-border mobility.

Sources from the eighteenth to the twentieth century shed light on the complex interplay among citizenship, rights, and belonging—three terms that are related but not interchangeable.

Citizenship and Rights

Originating in ancient Greece and the Roman Empire, the notion of citizenship broadly refers to a political community formed by a group of individuals with rights (and responsibilities), as opposed to a top-down relationship between a ruler and their subjects. The consolidation of European states in the seventeenth century was followed by the emergence of nation-states in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, giving rise to a distinct model of citizenship based on bonds among individuals united by a shared language, culture, and history. While this model remains dominant in the popular imagination, other models of citizenship also existed. One notable example is the imperial citizenship of the nineteenth-century Ottoman Empire, in which rights and duties were organized within an official framework that recognized religious differences.

Moreover, rights do not necessarily accompany formal citizenship. Sarah Abrevaya Stein’s and Jessica Marglin’s respective concepts of “citizenship as a spectrum” and “legal belonging” invite us to move beyond the binary of citizen-with-rights versus noncitizen-without-rights. They encourage us to consider how states—especially in colonial contexts—could confer legal rights even without granting full citizenship. Conversely, formal citizenship could, and often did, coexist with the denial of substantive rights.

The Concept of Belonging

Understanding the evolving relationship between Jews and the state in the modern period requires moving beyond the categories of citizenship and rights. The more elusive—yet no less important—concept of belonging adds a vital dimension, capturing emotional, cultural, and social ties to the state, along with the intracommunal debates that have shaped modern Jewish identities. Focusing on Jewish belonging(s) also shifts our perspective from the agency of the state to that of Jewish individuals. Jews were far from passive recipients of rights. Rather, they actively sought political and social inclusion, “performed” citizenship through daily practices intended to demonstrate their worthiness as citizens or prospective citizens, and employed a range of strategies to negotiate their status. In some cases, they rejected offers of citizenship or denied state-granted rights to their fellow Jews.

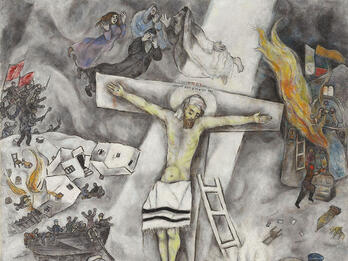

A wide array of sources—including memoirs, paintings, correspondence with state officials, personal essays, and other documents—illuminate the diverse paths to citizenship taken by Jews across various national, imperial, and postcolonial contexts. The voices captured in these materials also reveal shifting definitions and classifications of “Jews,” shaped through the negotiation of relationships between individuals and the ruling authorities.

Lessons for the Present: Rights, Diversity, and Inclusion

Understanding how Jewish rights and citizenship have been shaped, granted, denied, and contested across time and space raises broader questions with far-reaching implications. In an era marked by global migration and rising ethno-nationalism, questions of how to manage diversity, safeguard religious minorities, protect noncitizens, and balance individual and collective rights remain as urgent as ever. Jewish history ultimately reveals that citizenship is not a clear before-and-after condition but a contingent, contested, and nonlinear process. Rights can be expanded—but also curtailed—at any given time.

Learning Objectives

Analyze how the cultural and socioeconomic diversity of Jewish communities shaped their encounters with modern citizenship and generated new internal divisions over rights and identity.

Identify key turning points and continuities in the transnational history of Jewish belonging and interpret how struggles over Jewish rights reflected broader geopolitical forces.

Develop a nuanced, historically grounded understanding of rights and citizenship—and their multiple meanings—as lived experiences shaped by law, identity, and collective memory.

Apply comparative and analytical frameworks to connect historical case studies with current global debates around citizenship, exclusion, and legal belonging.