Class 1: From Tolerance to Citizenship? Jews and the Limits of Early Republic Inclusion

Enlightenment ideals and early U.S. laws—from colonial petitions to acts of Congress—defined the boundaries of Jewish belonging in the new republic.

From Collective Rights to Individual Citizenship

Historians of the West divide the early modern from the modern around the axis of citizenship and rights. Early modern political life from the 1500s through the 1700s tended to be organized around caste lines (think of the distinctions between peasants and nobility). Membership in a collective category determined one’s political rights and obligations. Modern political systems that arose beginning in the late eighteenth century embraced new Enlightenment ideas about the individual as the basis for rights. The French Revolution’s 1789 slogan of “liberty, equality, fraternity” embodied this modern spirit; people who had once been fettered by caste demanded recognition and rights as individuals.

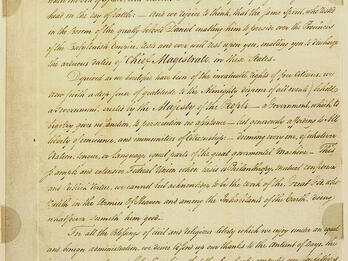

In many ways, the experiences of Jews in North American settlements can be plotted along these political shifts. Colonial powers in the late seventeenth century regarded Jews as a separate class, much as they were seen by most European powers. In seeking entry to colonies, Jews petitioned for rights as Jews, not as individuals. And to the extent they received them, they did so on collective terms. By the time of the American Revolution, however, Jews imagined a new political horizon, where the law classified them as individual citizens, due the same rights as any others.

The broad political transformations that ushered in modernity, however, reveal only part of the story of how citizenship—with its attendant capacity to validate an emotional sense of belonging—worked in the United States. The full story cannot be told without accounting for the myriad ways that laws, policies, and attitudes continued to challenge individual rights. Even as political leaders envisioned a country dedicated to liberal ideals, they simultaneously justified excluding whole swathes of humanity from the basic rights of equality. Enslaved people and women represented the most obvious exclusions. Political leaders mined and developed the language of sex and race to define these groups’ deviance from the norm of male and white personhood. They suggested it was natural and necessary to create thresholds for individual belonging.

Jews presented a puzzle to the founders of the United States. Did their Jewishness limit them from clearing the threshold tests for political membership? In earlier times, both in the North American colonies and other places they lived, Jews had sought rights through collective petitions. They requested toleration from Christian leaders much as they had in other national and imperial contexts. Under the sway of Enlightenment thought, however, some Jewish and Christian thinkers advocated a novel decoupling of political systems from religion. A classically liberal system organized around individual rights, they suggested, would pay no heed to a person’s religion, which could be exercised privately. In a world where lines of religion dissolved in civic life, perhaps Jews would not require tolerance.

Defining Jewish Difference

Jews posed two interrelated questions in the early republic. First, what was the basis of their difference? If Jews were simply members of a different religion, then their inclusion in the nation might be similar to that of Unitarians, Quakers, or Catholics. But their Jewishness might instead suggest differences more akin to those of native people, enslaved people, or women: differences that the founders generally believed justified exclusion. Furthermore, given Jews’ diverse origins and backgrounds, the classification of their differences could vary wildly.

Equality, Tolerance, and Distinctiveness in Debate

The second question that Jewishness raised was about the relationship between equality and difference. If political leaders merely granted Jews tolerance while still marking them as separate from the norm—for example, by establishing state churches or insisting that elected officials swear oaths on the Christian Bible—then this political system surely limited their equality. At the same time, though, such a system would not threaten to challenge the terms of Jewish difference or mandate assimilation. If, however, political leaders granted Jews total equality, abolishing institutions that excluded Jews, then might Jews, in turn, be expected to minimize or shed their differences? In other words, were full equality and distinct identity mutually exclusive goals?

The 1790 Naturalization Act: “Free and White”

The 1790 Naturalization Act defined people who were “free and white” as eligible for U.S. citizenship. Yet for Jews and many other people, the law continued to pose questions. Who exactly qualified as “free and white”? Would all those who qualified necessarily be granted equality, or simply tolerance? And, finally, which of the two was preferable?

Early Jewish Views on Belonging in America

These were complicated questions that would continue to shape Jews’ political experiences in the United States. Political leaders in the colonial and post-independence period often disagreed on the answers. Jews themselves also held varying views. Depending on their prior experiences, their social and economic backgrounds, and their connections to other groups of people, they had different expectations for how they would fit into the non-Jewish world.

Discussion Questions

What is the difference between receiving rights as part of a collective group versus gaining them as an individual? Why would a political leader prefer one or the other?

Under a liberal system of individual rights, why would some Jewish thinkers begin to insist that Jews were simply members of a religious group and were not distinctive in other ways?

What is the difference between tolerance and equality? What conditions would cause Jews to prefer one or the other?

Given the endurance of slavery and patriarchy in the early years of the United States, is it accurate to describe the political system as nonetheless embracing liberal ideals?