Who Is American? Citizenship, Law, and Jewish History in the United States

Jewish encounters with American citizenship, from the colonial era to today, reveal how the United States has continually redefined who belongs and why.

Citizenship, Rights, and American Identity

Who is American? From presidential orders repealing birthright citizenship, to the deportation of documented and undocumented individuals, to efforts curtailing or enriching the sometimes-competing rights of religious, trans, and pregnant people, today’s headlines announce the high yet deeply contested stakes of American citizenship and its boundaries. Since the settlement of European colonies in North America, new-world political leaders have employed citizenship laws to sort human beings. At the same time, individuals and groups rely on these laws to make claims about their identities, their relationships, and their world.

Jews and the Boundaries of Belonging

The topic of citizenship occupies very little space in scholarship about American Jews. Most historians have simply assumed that Jewish immigrants and their children had unfettered access to citizenship. Yet citizenship is rarely a binary proposition. One’s status as a citizen or non-citizen can change over time, depending on laws and policies. Furthermore, simply saying a person is a citizen communicates very little about the nature of their citizenship—for example, were Jews in the early nineteenth century the same kinds of citizens as white Christians? And the rules governing citizenship often compel groups of people to form or dissolve relationships with one another to safeguard or enhance their own rights.

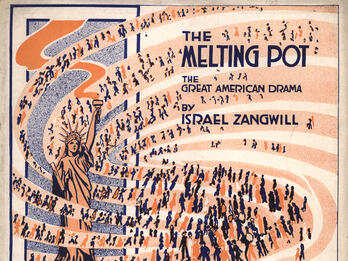

Jews’ encounters with citizenship law from the colonial period through the present offer a lens through which to witness the complex dynamics of both modern citizenship and American political life. Rejecting European models that conferred political rights on people according to their group or class, the architects of American law embraced the liberal ideal of individual rights. Even so, the earliest laws about citizenship in the United States conditioned individual belonging on collective classifications, including whether a person (in addition to being male, which was assumed) was white and free. A vast majority of people living in the early republic were considered to lack the categorical qualifications for individual citizenship. And some groups including Jews fell between categories of belonging, especially that of whiteness, leaving the status of their citizenship and its associated rights in question.

Local vs Federal Power in Citizenship Laws

A strong American national identity depended on solid citizenship laws, yet for the first century after American independence, state and local governments had more control over citizenship than the federal government. This localized arrangement of power led to stark variations in Jews’ civic status. Jews experienced vastly different rights across space, while also learning that their rights existed in relation to the status of other groups. National debates about abolition and women’s rights involved Jews, both because Jews often had personal stakes in the questions and because the answers to them could reshape fundamental ideals like equality and freedom in the United States. Even so, Jews, like other Americans, held a diversity of positions on these pressing matters, reflecting contested visions of American national identity.

Citizenship After the Civil War and the “Second Founding”

In the era after the Civil War, citizenship law emerged as the framework for the “second founding” of the United States. Through constitutional amendments and new laws, the country expanded its conception of national belonging, while also sharpening its tools to exclude entire groups of people from membership. New policies and bureaucracies gave government agents the ability to identify and restrict Jews from entry. Eventually formalized into law, exclusionary visions of American belonging did not exist only at the borders, but rather seeped into the daily experiences of those living within the United States.

Modern Struggles: Equality, Diversity, and Legal Limits

By the middle of the twentieth century, American citizenship underwent another revolution, marked by new immigration policies and sweeping civil rights legislation. Yet far from settling the status of Jews, these legal transformations raised questions about their national belonging. In debates ranging from questions about the legality of affirmative action to whether antidiscrimination laws adequately protected Jews against antisemitism, political figures and Jewish leaders grappled with the complexity of laws premised on individual equality that nonetheless treated people according to collective terms. Once again, they grappled with where Jews fit within a hybrid system of individual rights and collective thresholds.

One might imagine that laws should be able to answer clearly who belongs in the United States, and laws should be able to guarantee that citizens all possess equal rights. A historical lens, however, allows us to appreciate the limits of law and to learn that citizenship and civil rights exist in living communities with diverse interests, desires, and viewpoints. The past, as much as the present, struggled to resolve how to balance the reality of a diverse citizenry with an ideal of equality in the United States.

Learning Objectives

Discover how American citizenship has changed over time and reflects political, economic, and cultural transformations in the United States and the world.

Develop mastery over key historical episodes when local, state, and federal officials defined Jews’ place in the polity and their relationship to other categories of citizens and noncitizens.

Analyze how different Jewish people responded to the challenges of national belonging and how their responses fostered alliances with or divisions from other groups.

Engage in informed and historically grounded reflection about current-day debates over who may become a citizen and the rights that different types of citizens may exercise.