Class 2: Jews, Slavery, and Citizenship in Nineteenth-Century America

Jews engaged with 19th-century debates over slavery, women’s rights, and equality, revealing how American citizenship granted and withheld freedoms.

The Nineteenth Century as an “Age of Questions”

Historians have described the nineteenth century as “The Age of Questions.” On the heels of political revolutions, people contemplated new ways to organize society, but many also feared the consequences of dismantling old hierarchies and power structures. How did non-white people, women, non-Christians, and other “others” fit into new social and political orders? Posed both by groups that had been historically excluded from channels of power and by the holders of that power, the cascading questions of the nineteenth century resulted in reformist movements (such as abolitionism and the women’s rights movement) and reactionary efforts (such as immigration restriction).

Jews and the National Debate on Slavery

In the United States, the question of slavery forced the deepest national debates, eventually splitting the country into warring factions. Like other broad questions of the nineteenth century, slavery exposed sharp social cleavages and intractable regional divisions. When Americans, including free and enslaved people, challenged the viability and desirability of the system of slavery, they were also asking whether it was possible for the United States to maintain a coherent set of laws and policies—in other words, could it truly be a unified nation?

Jews living in antebellum America (from the early nineteenth century until the Civil War) could not avoid the question of slavery or the regional chasms it produced. They participated in debates about it in some ways that were similar to how other Americans approached the issue, and in others that reflected the social, economic, and political position of Jews living in a predominantly Christian society.

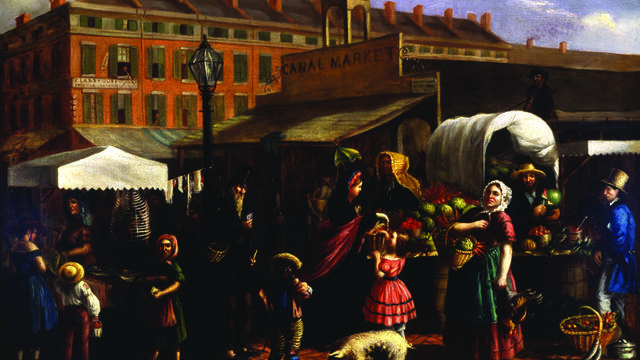

Throughout the nineteenth century, many Jews made their living by traveling across state and regional lines as peddlers (an early version of a traveling salesperson). Their peripatetic lifestyle gave them a firsthand understanding of the diversity of attitudes and ideas in the United States. Alongside cultural variations, profound legal and political differences separated states and regions. Jews might have noticed, for example, that a free Black person in one state could be arrested as a suspected fugitive in another. Likewise, they might have witnessed how similar variations marked Jews’ civil status as well. Depending on whether a state had an established church or required elected officials to swear a Christian oath, Jews’ opportunities could be markedly different depending on where they lived.

Regional Divides in American Jewish Life

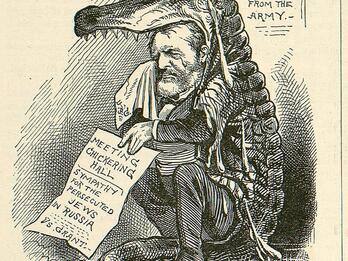

The same regional divisions that challenged any sense of a shared national culture appeared within American Jewish life. Jews who owned enslaved people or participated in slaveholding economies were likely to take very different sides on debates about slavery than Jews in the North. Jews’ position on the question of slavery in part stemmed from their circumstances, but it also reflected their interpretations of Jewish texts, their attitudes toward liberalism and individual rights, and their conceptions of freedom. At least one edge of the slavery debate among Jews overlapped with broader questions about whether a country that systematically denied rights to one group of people would safeguard the rights of other groups, including Jews. Indeed, anguish about the interrelationship between enslavement and Jewish rights amplified during the Civil War, when a Union military order expelled Jews from border regions on the suspicion that they were treasonously trading with Confederate powers.

Women’s Rights, Citizenship, and Jewish Belonging

An understanding of political rights as linked among groups—that the denial of rights to one group affects the rights of other groups—slowly developed in the nineteenth century. The same questions raised by slavery about how a liberal political ideal could sustain itself in the face of illiberal exclusions generated similar questions about women, who almost uniformly lacked political and economic rights, especially after marriage. Some Jews saw the degradation of citizenship rights, whether for Black people or women, as a simultaneous threat to American liberalism and to Jewish belonging.

Linked Rights: How Exclusions Affected Jews

The “Age of Questions” did not usher in an age of answers, but it produced new patterns of political thought. The insight that different groups’ rights tended to be linked together occasioned new alliances, with prospects for political movements to overturn legal inequality and exclusion. The Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868, introduced a bold new vision of citizenship. Replacing the patchwork of local and state policies, the law pledged the federal government to provide equal protection to all people and guaranteed citizenship for any person born in the United States. And yet the same insight about linked rights instilled fear, especially as group-based discrimination continued to thrive even amid new legal protections. For some Jews, the safest possibility was to emphasize their difference from other maligned groups—to prove why they were more fit for American belonging than those groups whose rights remained in question.

Discussion Questions

By the mid-19th century, some American thinkers agitated for a strong government, while others wished to protect state and local power. What factors might have caused Jews to prefer one model over the

How can the conception of linked rights foster coalitions, and in what ways might it harden lines of division?

What are the broad social questions of our own time that implicate many different people and reflect on the basic values of the United States?