The Rise of Kabbalah

Kabbalah spread widely after the Spanish expulsion. The Zohar's printing in Italy, Safed's influential kabbalistic center, and Shabbetai Tzvi's messianic movement popularized mystical ideas across Jewish communities.

Kabbalah, a system of religious and mystical thought that emerged at the end of the twelfth century in Provence, formed a central feature in the culture of many Jews expelled from Spain. Their dispersal hastened its dissemination, especially among the Jews of the Mediterranean basin and the Near East. Kabbalah came to attain a status in the Jewish world it had never previously achieved. Study of kabbalah, which until then had been restricted to small circles of adepts, began to spread among the Jewish masses. Moreover, the dispersal of the Sephardic Jews brought with it the diffusion of kabbalistic manuscripts, and the study of kabbalah developed more local variants, each depending on which manuscripts were accessible.

The core of kabbalistic learning was the Zohar, a mystical work (made up of several layers and related texts) attributed to the second-century rabbi Shimon Bar Yoḥai but actually composed in thirteenth-century Spain by a circle of scholars associated with Moses de Leon, under circumstances that are still unclear. Before it was printed in Italy in the mid-sixteenth century, there was no uniform text of the Zohar, and zoharic manuscripts, each quite different from the rest, were disseminated without any consensus as to which belonged to authentic source material. During the first generation after the expulsion, however, Jewish centers in North Africa in particular played a pioneering role in collecting and editing these zoharic texts. Among the Sephardic rabbinic scholars who relocated to Morocco were several prominent authors of works closely connected to zoharic literature. One of these, Abraham Ardutiel, while in Fez, wrote an anthology entitled Avne zikaron (Stones of Memory), containing texts from a number of kabbalistic works, including previously unknown passages from the Zohar.

North African Jewry, especially in the Maghreb, helped to transform the Zohar into a holy book in and of itself. As Lawrence Fine has written, “The Zohar was ever so gradually embraced as an object of veneration and employed for a variety of ritual and devotional purposes by ordinary folk, possibly including women.”1 Groups of Jewish men, including simple people, gathered regularly to study the Zohar, sometimes reading or chanting it without necessarily paying attention to the meaning of the text. Special times were set aside for these practices. The usual time to study devotional or mystical texts might be before or after prayers, late in the evening, on the Sabbath eve or close to the end of the Sabbath, but now reading the Zohar made its way into the liturgical calendar itself. It was studied on the eve of Lag b’Omer (day 33 of the Counting of the Omer, which takes place between Passover and Shavuot), Hoshanah Rabbah (the seventh day of Sukkot), the evening of a circumcision, during shivah (the seven-day mourning period after a death), or as a ritual in the home of someone mortally ill. These customs arose and developed because of a growing popular faith in the sanctity of the Zohar and in its spiritual and magical qualities.

The Zohar thus became a venerated book. In certain communities, possessing a copy of it in one’s home was thought to provide protection against the evil eye. Healing powers were attributed to it. Shimon Bar Yoḥai, the “author” of the Zohar, became a revered saint among Jews of North Africa. Endowments for scholarship devoted to his memory were established in various places. For members of these groups, Lag b’Omer became a special festival, during which the Zohar and its purported author were celebrated with fasts, songs, and dances, as well as study.

The kabbalah struck particularly deep roots among the Jews of Draa in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco, who had lived in the area from a very early time and preserved ancient traditions. Influenced by beliefs of the Muslim Marabouts of their surroundings, they developed a kabbalah centered on mystical experiences associated with Elijah the Prophet, based on a strong connection with the holy spirit, and that invoked visions inspired by dreams. Some of the customs of the kabbalists of Draa later reached the kabbalists of Safed, apparently through the influence of Moroccan kabbalists who immigrated to the land of Israel, such as Abraham ben Eliezer Halevi.

The arrival in Italy of important Sephardic kabbalists, including Judah Ḥayyat, Isaac ben Ḥayim ha-Kohen, and Abraham ben Eliezer Halevi, during the generation of the expulsion from Spain, placed Italy in the center of kabbalistic activity for the following generation. The printing revolution, centered in Italy, also influenced the spread of study of the Zohar. Some kabbalists opposed the publication of the book, arguing that not everyone was worthy or qualified to study the holy work. Nevertheless, between 1558 and 1560, a version of the Zohar based on ten different manuscripts was printed in Mantua, in three volumes. A competing printer in Cremona in 1559/60 published a Zohar based on yet other manuscripts, in one volume. Regarding these two editions, Robert Bonfil has noted that “while the Mantua edition was directed toward the Ottoman markets, the Cremona edition was directed toward those of eastern Europe.”2

After publication of the Zohar, the study of kabbalah underwent a significant shift: a field that had previously been regarded as esoteric became terrifically popular, even to the extent of competing with traditional rabbinic literature. This situation stimulated Leone Modena to write a vehement polemic against kabbalistic works, called Ari nohem (Roaring Lion), in which he challenged the antiquity of the Zohar. Opponents of kabbalah could be found in the Ashkenazic world as well. Moses Isserles belittled those who were overly anxious to study it, and later, Jacob Emden questioned its authenticity altogether.

The Kabbalah of Safed

Among the new centers of kabbalah established by the Jews expelled from Spain, the most important arose in Jerusalem and Safed. The center in Jerusalem flourished only in the first half of the sixteenth century but included such prominent kabbalists as Abraham ben Eliezer Halevi and Judah Albotini. However, at midcentury, kabbalists left Jerusalem for other centers, and Safed became a vibrant center whose influence eventually spread through the entire Jewish world. There, central figures such as Joseph Karo, Solomon ha-Levi Alkabetz, his brother-in-law Moses Cordovero, Eleazar Azikri, and Elijah de Vidas spurred flourishing kabbalistic activity.

The Safed kabbalists developed their own, far-reaching kabbalistic theology that centered the concept of exile. As they saw it, the historical exile of the Jewish people reflected the metaphysical exile of the shekhinah (the divine presence), the female dimension of the divinity. They believed that fulfilling religious obligations, and in particular penitence, prayer, and devotion in prayer, had the power to redeem the shekhinah from her exile.

In his Pardes rimonim (Garden of Pomegranates), Moses Cordovero offered a synthesis between Spanish kabbalah, which focused on the Zohar, and elements of ecstatic kabbalah. Cordovero died in 1570, six months after the arrival of Isaac Luria, known as “the holy ARI” (an acronym of his name, meaning “lion”). Luria was born in Jerusalem and educated in Egypt in the circle of David Ibn Abi Zimra. Upon his arrival in Safed, Luria joined the circle of Cordovero’s disciples. Luria died two years later, but during his two years in Safed, he attracted about forty disciples with his charismatic power. While he left almost no writings behind, and his teachings have come down to us only through his disciples, especially Ḥayim Vital, he shaped an important new strain of kabbalah: Lurianic kabbalah.

Prior to Luria, the kabbalah presented the initial, divine act of creation as one of wholeness, which earthly redemption would restore. In contrast, Luria believed that the act of creation began with a kind of rupture in the divine plan, which he called “the smashing of the vessels.” So that his disciples could meld their souls with the divinity and repair the breaks, he demanded that they first repair their own souls and purify themselves of their transgressions by means of rituals connected to specifically kabbalistic intentions in performing the commandments. According to Luria, human actions—especially observance of the commandments—play a central role in the cosmos and have cosmic significance. If the individual keeps the commandments with the proper intention, the shekhinah will be redeemed from her exile and reunite with God.

Intense messianic fervor motivated the kabbalists of Safed in their way of life and their pietistic and ascetic customs in particular. Following generations absorbed Lurianic kabbalah, in various guises and forms, into Jewish practice and belief in developments.

Messianic Upheaval: Shabbetai Tzvi

In 1666, an intensely powerful messianic movement shook the Jewish world, centered on the person of Shabbetai Tzvi who claimed to be the messiah—with Nathan of Gaza as prophet and propagandist of the movement. The subsequent upheavals affected nearly the entire Jewish world. News of Shabbetai Tzvi’s activities reached almost every country with a Jewish community.

Nathan of Gaza was a kabbalist who drew upon the teachings of Isaac Luria, and many of his writings were permeated with kabbalistic terminology. Scholars debate the significance of Lurianic kabbalah in this messianic movement. Gershom Scholem, in his highly influential study of Shabbetai Tzvi, argued that Nathan’s use of Lurianic kabbalah resonated with Jews, encouraging the spread of the belief that Shabbetai Tzvi was the messiah. Moshe Idel, on the other hand, has objected that Lurianic kabbalah was not as generally widespread as Scholem claimed. In his opinion, too, Shabbetai Tzvi was not himself a Lurianic kabbalist. Finally, Matt Goldish has concluded that “the judicious historian should not read the long and complex history of Sabbateanism mainly through a whiggish lens, determining its significance according to its impact on later developments. It should rather be seen as a set of ideas and events that reveal a great deal about its own historical contexts, teaching us about the horizons of Jewish identity in the early modern era.”3

The Arrival of Kabbalah in Eastern Europe and Germany

The kabbalah of Safed penetrated Germany and Eastern Europe. In 1592, Moses Cordovero’s Pardes rimonim (completed in 1549) was printed in Kraków, only about eight years after it was first published in Salonika. Although this book was not printed again in Eastern Europe until the end of the eighteenth century, other works by Cordovero, intended for a more popular audience, were printed during the seventeenth century in Prague, Kraków, and Fürth.

In Eastern Europe, Isaiah Horowitz had the most influence in introducing the kabbalistic tradition. Born in Prague, he served as the rabbi in several major Jewish communities such as Poznań, Kraków, Frankfurt, and Prague, eventually being appointed rabbi of the Ashkenazic community in Jerusalem in 1621. His most famous work, Shene luḥot ha-berit (Two Tablets of the Covenant; Amsterdam, first half of the 17th century), is an encyclopedic compendium containing a discussion of almost every topic in kabbalah. The book was reprinted many times, and Horowitz came to be known by the title of his book.

Kabbalah was increasingly popular among the Jews of Eastern Europe—and increasingly available in Yiddish. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, Kav ha-yosher (The Just Measure; Frankfurt, 1705), was one of the most influential and widely circulated Jewish books on kabbalistic ethics. The author, Zvi Hirsch Koidanover, born in Vilna, later prepared a bilingual, Hebrew-Yiddish edition of the book. Sections of the Zohar even appeared in a Yiddish translation, by Tzvi Hirsh Khotsh, called Naḥalat tsvi (A Goodly Heritage; Amsterdam, 1711). As Chava Weissler has pointed out, “A dilemma [was] faced by all popularizations of mystical material: How can one make available to the masses a text such as the Zohar . . . which had for centuries been studied only by an elite coterie?”4 Yiddish translations indicate that these kabbalistic works circulated among a wide readership, one that included women.

Notes

Lawrence Fine, “Dimensions of Kabbalah from the Spanish Expulsion to the Dawn of Hasidism,” in The Cambridge History of Judaism, vol. 7, The Early Modern World, 1500–1815, ed. Jonathan Karp and Adam Sutcliffe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 444–445.

Robert Bonfil, “A Cultural Profile,” in The Jews of Early Modern Venice, ed. Robert C. Davis and Benjamin Ravid (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001), 182; Isaiah Tishby, Studies in the Kabbalah and Its Branches [Hebrew] (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1982), 1:79–130.

Chava Weissler, Voices of the Matriarchs: Listening to the Prayers of Early Modern Jewish Women (Boston: Beacon Press, 1998), 56.

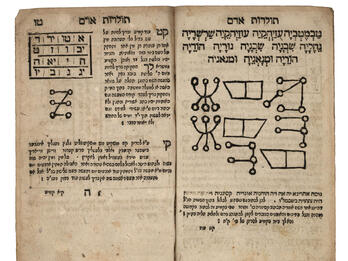

![M10 622 Manuscript, probably from Ukraine]. Manuscript probably from Ukraine, c. 1740 with a broad collection of practical kabbalah and mystical magic. Facing page manuscript arranged vertically with Hebrew text in the shape of a figure wielding two long objects.](/system/files/styles/entry_card_sm_1x/private/images/vol05/Posen5_blackandwhite166_color.jpg?h=cec7b3c9&itok=Sz6u21MQ)