Class 3: Stateless Jews and the Politics of Papers, 1918–1948

Explore how 1918–1948 forced European Jewish refugees to navigate statelessness, closed borders, and the life-or-death politics of passports and papers.

From Empire to Nation-State: The Birth of Statelessness

Contemporary debates about migration often rely on dichotomies such as emigrant/refugee or legal/illegal immigrant. These categories trace back to World War I, when the collapse of empires gave rise to modern immigration regimes and an international legal framework that still shapes how movement across borders is defined and controlled. The experience of European Jews between the wars and during the Holocaust illustrates how these systems developed—and how they continue to affect lives today.

Jews Between Wars: Rights Lost and Borders Closed

Despite peace treaties intended to protect minorities, citizenship remained elusive for many Jews in the newly independent states of Eastern Europe. Without the right papers proving prewar residence, they were classified as foreigners; even those recognized as citizens faced restrictions. Social marginalization and economic crises pushed many to seek opportunities abroad, but rising nationalism tightened borders, making documents, such as identity cards and passports, crucial. Those who reached Western capitals without proper papers risked expulsion, while others—deemed “undesirable”—were stranded between states that denied them entry and homelands that had denationalized them, an experience chronicled in Joseph Roth’s The Wandering Jews.

The League of Nations and the First Refugee Regime

Jews shared this plight with millions of other refugees rendered stateless after the war—people without rights because they lacked a formal bond to any state. In the 1920s, the recently created League of Nations attempted to address their vulnerability, especially that of Russian and Armenian refugees, by creating “Nansen passports.” These were provisional documents that conferred limited legal recognition but offered weak protection. The refugee regime had just been born, but it would fail when European Jews most needed it.

Denaturalization and Persecution in Nazi Europe

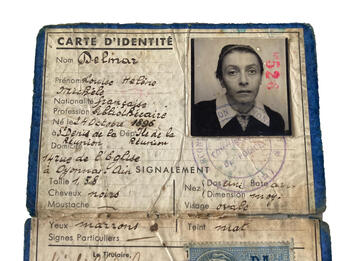

In the 1930s, the collapse of democracy on the European continent exposed the fragility of citizenship. In Germany, the Nazis made denaturalization one of their earliest tools of discrimination, formalizing racial antisemitism by defining Jews through ancestry rather than religious affiliation or self-identification. Other states followed, including Vichy France, which stripped thousands of recently naturalized East European Jews of their rights, as well as Algerian Jews who had become French in 1870. Denaturalization became the first step toward genocide.

Central to the mass arrests, deportation, and eventual systematic murder of Jews was the ability to identify them as such. States developed bureaucratic tools such as identity cards marked with “J,” as shown in Felix Nussbaum’s Self-Portrait. These documents became a matter of life and death. No wonder then that resistance fighters—many of them Jewish—devoted considerable time and energy to forging papers, such as Olga Kagan-Katunal’s false identity cards. Famously, Adolfo Kaminsky, a member of the French Resistance, is credited for saving no fewer than 14,000 lives through his forgeries.

Papers and Survival: Bureaucracy in a Time of Peril

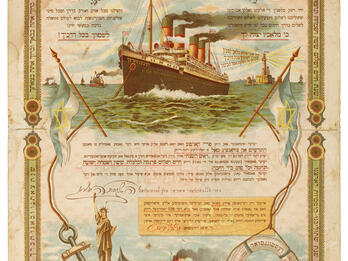

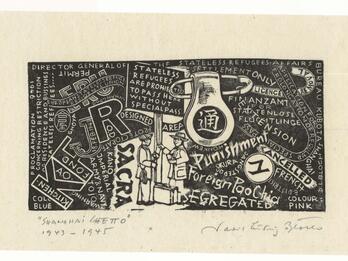

Papers were equally crucial in the search for refuge. In the 1930s and 1940s, most countries, including the United States with its restrictive 1920s quotas, shut their doors to Jewish refugees. Thousands found unexpected shelter in Shanghai, China, which required no visas for entry; their experience is commemorated in David Ludwig Bloch’s woodcut “Shanghai ghetto.” At every step, survival depended on documentation—exit visas, safe conducts (travel papers), and entry permits. A handful of non-Jewish diplomats from Sweden, Japan, Poland, and Spain saved thousands by issuing protective passes, transit visas, or forged passports.

Exile and the loss of citizenship provoked a sense of despair that shaped refugees for the rest of their lives. These experiences prompted Jewish jurists and intellectuals to pioneer efforts to define the refugee experience, as Hannah Arendt did in her essay “We Refugees,” and to construct a legal framework for human rights after World War II. Arendt’s idea of a “right to have rights” remains especially poignant as contemporary crises echo those past displacements.

Discussion Questions

In many ways, the decades that preceded the Holocaust paved the way for the mass murder of Jews in the 1940s. How did the circumstances of European Jews in the 1920s shape their later fate?

How did Jews respond to the increasing precariousness of their legal status in the interwar period?

Compare and contrast the descriptions of the “refugee” experience in the different sources presented here.