Class 4: The Law of Return and Jewish Belonging in Israel

Explore how Israel’s Law of Return shaped Jewish citizenship, identity, and exclusion from 1948 to today.

The Meaning of “Return” after 1948

In 1948, after a genocide that killed more than a third of the Jewish people, the State of Israel was founded, giving Jews political sovereignty for the first time in nearly two thousand years. In the decades that followed, Israel became home to the world’s largest Jewish population. After centuries as subjects or minority citizens, Jews now had to navigate the boundaries of national sovereignty and rethink belonging, rights, and citizenship. The idea of “return” resonated deeply, promising a protective home for Holocaust survivors and refugees from Middle Eastern and North African countries. Yet as a foundation for nation-building, this idea has also produced enduring exclusions.

The Law of Return and the Question of “Who is a Jew”?

The question of “Who is a Jew?” emerged as a central challenge from the state’s inception. In 1950, when the Israeli Parliament enacted the Law of Return, granting all Jews the right to immigrate to Israel and obtain citizenship, it notably left the term Jew undefined. As bureaucrats were increasingly required to categorize individuals and ordinary people sought to understand their rights, the courts were compelled to address this thorny issue. Cases of intermarriage and conversion highlighted tensions between secular Zionist visions of Jewish identity and traditional religious definitions, which hold that a Jew is someone born to a Jewish mother or converted under Orthodox standards. In a letter to fifty prominent Jewish thinkers, Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion sought to address the status of children of a Jewish father and a non-Jewish mother whose parents wished to have them registered as Jewish. A related question came before the court in the case of Brother Daniel, a Jewish-born Carmelite monk who sought Israeli citizenship under the Law of Return. Though according to Jewish religious law, a Jew who converted to another religion would still be considered a Jew, both the majority and the dissenting opinions maintained that Jewish status for the purpose of the Law of Return had to be determined by other criteria. In 1970, a legal compromise produced two coexisting definitions: a secular one based on ancestry that governs immigration rights, and a rabbinical one rooted in Jewish law, which regulates personal status issues such as marriage and divorce. As ongoing controversies over marriage, conversion, and religious authority continue unabated, the question of who may “return” remains unresolved.

Citizenship and Exclusion: Mizrahi Jews and the Ashkenazi State

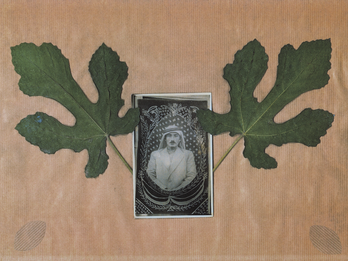

The social, cultural, and economic marginalization of non-European Jews in the state’s early years also complicated the notion of return. In the 1950s and 1960s, Jews from North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia began new lives in the young state. Though many of these immigrants, often called Mizrahi (“Eastern”) Jews, were driven out of their countries of origin, the circumstances of their migration were often more complicated and ambivalent than those of Ashkenazi Jews rendered stateless by the Holocaust, as discussed in Ella Shohat’s “Rupture and Return: Zionist Discourse and the Study of Arab Jews.” Although formally granted the same rights as Ashkenazi Jews of European descent, Mizrahi immigrants faced institutionalized racism and systemic discrimination at the hands of a state bureaucracy staffed and directed primarily by officials of Central and Eastern European origin, who imposed their own cultural assumptions and administrative norms. Many endured harsh conditions in transit camps (ma‘abarot) and were later resettled in remote development towns with limited access to education and economic opportunity. Cast as “Oriental” and culturally backward, they were subject to assimilationist policies that led to significant cultural loss, particularly among Jews from Arab countries. However, through political mobilization and public protest—such as the Wadi Salib riots in 1959 and the Israeli Black Panthers movement in 1971—Mizrahi communities pushed back and expanded their civil and cultural rights. Today, many Israelis are returning to their families’ stories and roots through documentation, music, and other forms of cultural revival, reclaiming narratives that have long been suppressed.

Arab Citizens and the Limits of Belonging

The gap between legal citizenship and substantive citizenship is most visible in the case of Israel’s Arab minority, which constitutes roughly one-fifth of its population. In 1948, some 750 thousand Palestinian Muslims and Christians fled or were forcibly expelled during the war and were subsequently denied the right to return. The Nationality Law of 1952 granted citizenship and voting rights to many of the Palestinians who remained within Israel’s borders, but only on the basis of strict residency requirements, contrasting starkly with the automatic citizenship granted to Jewish immigrants. Among the critics of this disparity were some Jewish observers otherwise supportive of Zionism, such as the philosopher Simon Rawidowicz. In practice, even Palestinian Arabs with Israeli citizenship often face discrimination and social disparities and lack full belonging in the Jewish state. The 2018 Nation-State Law, which enshrines Jewish self-determination as the exclusive right of the Jewish people in the State of Israel, further codified this exclusion in legal terms.

Return Reversed: Israelis Seeking European Citizenship

Further complicating the meaning of “return,” in recent years a growing number of Israeli Jews have begun seeking citizenship in Europe. Countries such as Germany, Portugal, and Spain have offered citizenship to individuals whose ancestors were persecuted during the Holocaust—or, in the case of the Iberian Peninsula, expelled during the Inquisition five centuries ago. The motivations behind these applications vary: some are emotionally driven by a desire for historical closure or family connection, while others are more pragmatic, seeking economic or educational opportunities in the European Union. Whatever the reason, this reversal reveals that the story of Jewish belonging, identity, and citizenship remains dynamic and contested.

Discussion Questions

How did the creation of the State of Israel alter the landscape of Jewish rights after World War II?

How did the shift to political sovereignty affect Jews’ understandings of identity and memory both within Israel and in the diaspora?

What kinds of exclusion did the notion of “return” create, and how does the distribution of rights in the State of Israel reflect the gap between formal legal status and belonging?