Class 3: Jews, Immigration, and Belonging in Post–Civil War America

United States border laws after the Civil War—from Chinese Exclusion to racialized immigration policy—reshaped citizenship and Jewish belonging in America.

Securing Borders in Post-Civil War America

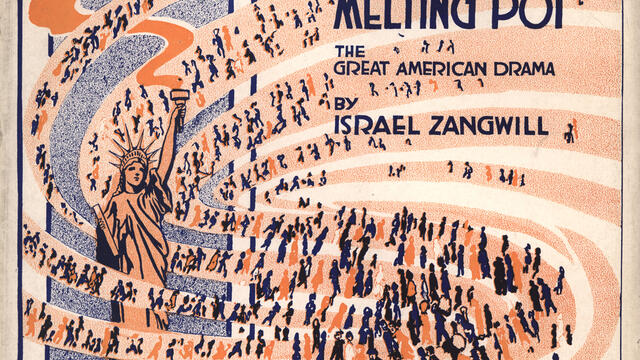

Borders designate the edges of territories, but when it comes to national identity, they can also shape the interior. From the end of the Civil War to the 1920s, the United States secured its borders in unprecedented ways. A newly empowered and centralized federal government passed legislation restricting the numbers and types of immigrants who could gain entry. At the same time, it built a massive bureaucracy, with border agents, paperwork, and a judicial arm, to classify potential entrants. The fortified border reflected roiling anxiety about American identity that seeped into the lives of American Jews who understood exclusions against Jewish immigrants and other groups of immigrants as a referendum on their own belonging in the United States.

The Chinese Exclusion Act and Its Legacy

Core to the project of securing American borders was the refining of the calculus of who truly belonged in the country. After the Civil War, the border-drawing process helped reunite a sectionally divided nation. Instead of a line bisecting the country between the North and South, the border could be refashioned to distinguish between American and un-American. Asian immigrants emerged as the first targets, with the Chinese Exclusion Act passed into law in 1882. In part, the effort to constrict the flow of immigrants from China reflected economic pressures. Yet those pressures were inseparable from nativist and discriminatory ideas. White laborers resented companies that hired lower-paid Chinese workers. They channeled some of that resentment into labor politics to guarantee better wages and working conditions. But riled by populist political leaders, white laborers also blamed Chinese people for stealing jobs and weakening the country. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 foreshadowed nearly half a century of restrictive immigration policy and citizenship law premised on group exclusion. For example, people designated as “Asiatic,” other than those who were born on American soil, had no pathway toward citizenship.

Jews and the Racialization of Immigration Law

At the turn of the century, federal judges regularly heard cases from petitioners marked as non-white and thus ineligible for citizenship by border agents. These petitioners, arriving from places in the modern Middle East, Turkey, and India, all sought to prove that because they were not “Asiatic,” they should be admitted as white people for citizenship. The complexity of applying invented and ever-changing racialized categories to legal deliberations led to inconsistent decisions and often validated prejudicial assumptions. Even as they rendered opinions, judges routinely beseeched Congress to offer more clarity about the categories that differentiated between people who did and did not qualify for citizenship.

The Dillingham Commission and Classification

Beginning in the early twentieth century, Congress sought to provide more clarity to the question of American belonging. In 1907, it convened a commission (called the Dillingham Commission) to study immigration and to provide recommendations for better standards and procedures. Alongside its foreordained conclusion that the pace of immigration was a problem, the commission sought to classify immigrants, some by country of origin like German, and others by racialized terms like “African (black)” or “Hebrew.” Even as the commission promised precision, it produced a tangled data set.

The relatively abstract idea about linked rights that had stirred some Jews in the nineteenth century to see their own possibilities for freedom and equality as connected to those of other groups grew far more concrete by the first decades of the twentieth century. If Jews were classified as comparable to groups that were marked as either disqualified from citizenship or undesirable, then this could slam the door on hundreds of thousands of Jews who annually found security and economic opportunity in the United States. Furthermore, the border policy could bleed into national consciousness and fuel prejudice against Jews as un-American.

Jewish Advocacy, Policy, and Public Opinion

Some elite Jewish leaders attempted to intervene in immigration policy, even gaining a hearing before the congressional commission. They tended to accept the necessity of restrictions on immigration—and railed against radical voices that protested government power. They focused their energies instead on trying to prove the value of good immigrants, the kinds who could contribute to American economic expansion. They also sought to convince Congress to excise racialized classifications of Jews, which they feared would prove that Jews were unassimilable, from its regulations.

Other Jews who could not get the attention of Congress lobbied in the court of public opinion. They wrote about all the ways that immigrants enhanced the United States. Still others helmed Jewish agencies that conducted citizenship classes and provided job training and educational resources, in part so that Jews would avoid being labeled as “likely to become a public charge,” a classification that border officials used to exclude newcomers who they determined had no means to support themselves.

In all of these ways and more, the policies at the border ricocheted into the interior of the United States, introducing new divisions not only between citizens and noncitizens but also among different kinds of citizens.

Discussion Questions

In the wake of the Civil War, why would the federal government focus so much energy on defining citizenship and restricting immigration?

"Why might Congress have sought to classify Jews as “Hebrews,” even though most Jewish immigrants came from Europe and others arrived from the Middle East, Turkey, and beyond?"

For a person who was already an American citizen, how might immigration restriction still affect their status?

What similarities or differences exist between the border control policies described here and current-day ones?