Class 1: Sephardic Women and the 19th Century Struggle for Equality

Sephardic women from Beirut to London shaped nineteenth-century debates on gender, rights, and Jewish identity through literature and reform.

Sephardic Jews and the Global Movements for Women’s Rights and Equality

The nineteenth century was a time of sweeping changes in the rights of women and minorities and a period of vast migration. Campaigns for gender parity featured not only among American and British women, but also in the Haskalah (the Jewish Enlightenment movement), and the Nahda Movement (Arab Renaissance), which focused on reforms and equality for all citizens, regardless of race, gender, or religion. How did Sephardic Jews, a religious minority community, participate in debates on human rights, influence Jewish/non-Jewish relations, and mold attitudes about immigration?

Sephardic Women Writers of the Nineteenth Century: Voices of Reform and Resistance

The first class will introduce a number of Sephardic Jewish women of the nineteenth century as important thinkers, fiction writers, and poets. Esther Azhari Moyal, a woman from Beirut who wrote in both Arabic and Hebrew, was part of the Nahda Movement. She was a fierce advocate of women’s rights, and challenged claims that women were the weaker sex. In a very different vein, a Salonikan woman named Reina ha-Kohen celebrated the strength of women as she beseeched them to be virtuous. Both women demonstrated their learnedness and multilingualism and provided evidence for their claims—claims that are ultimately worlds apart.

Grace Aguilar, Emma Lazarus, and the Making of Jewish Literary Modernity

Grace Aguilar and Emma Lazarus, two authors from similar time periods but with very different writing styles and audiences, both consider the treatment of Jews and other minorities in their work. Grace Aguilar’s story “The Escape” is both an exemplar of early English-language Sephardic literature and a fascinating tale of women’s agency. It also tells us a great deal about Aguilar’s intended audience: not only fellow Jews, who were devoted fans, translating her writing into German, Hebrew, and Jewish languages of Yiddish and Judeo-Arabic, but also a white, Christian, British readership that was not entirely enthusiastic about London’s (then primarily Sephardic) Jewish community. Aguilar aligns British Victorian and Jewish values while simultaneously stressing the whiteness of Jews, a perspective that many might find uncomfortable today. In contrast, Lazarus’s poem is widely beloved, with pride of place in American iconography. But Lazarus did not live to see her words affixed to the Statue of Liberty.

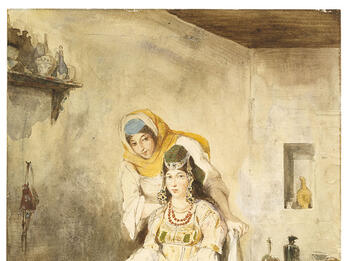

Representing Sephardic Women: Between Self-Portrait and Orientalist Gaze

The outpouring of ideas by Sephardic women, and the ways they represented themselves through their cultural outputs, contrast starkly to their representation by others. Contrast the language of Azhari Moyal, who championed female intellect, to the paintings, photographs, and portraits made of Sephardic women by European men. Inevitably, they are portrayed as dancers, washerwomen, or highly ornamented wives. Rather than showing women’s cerebral strengths, these images frame them as exotic, colorful objèts d’art.

In this class, we will consider materials and figures from London, Beirut, Salonika, New York, Tangier, Jerusalem, and Chicago to get a sense of the global impact and perceptions of these Sephardic women. Additional sources extend the conversation geographically and temporally.

Discussion Questions

Given 19th-century Maskilim translation efforts, can you trace how non-Jewish thinkers may have influenced or shaped conversations among these Sephardic women writers?

In what ways, if any, do these writers change your perception of women in the 19th century?

How do these sources—both the writing and the images—communicate ideas about Jewishness?

What might Azhari Moyal, attending the 1893 World’s Fair Women’s Congress, have thought of J. J. Gibson’s filmed dance? How does the contrast between an exotic dancer and a scholar shape our reading?"