Class 2: Becoming “Mizrahi”: Cultural Expression and Identity through Art and Story

Mizrahi Jews of Iraqi, Yemenite, and Tunisian heritage used arts and culture to challenge inequality and shape identity in Israel and beyond.

How the Mass Migration of Jews from Arab Lands Transformed Israeli Society and Culture

In Class 2, we turn to the twentieth century and the experiences of Jews of the Middle East and North Africa who either immigrated to the new State of Israel or carved out their identity in relation to Israel. After the signing of the 1917 Balfour Declaration by the British government in support of a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine, Muslim and Arab attitudes toward Jews in the Middle East and North Africa began to change. Well established in business, government, and the arts, Jews saw an erosion of rights and later an eruption of violence toward them. In the period of 1948–1967, Jews from Muslim and Arab countries—about 850,000 of them—were uprooted from their homes and homelands. Most moved to the fledgling Jewish state.

Life in Transit Camps and the Making of Mizrahi Identity in Israel

In Israel, these Jews were deemed Mizrahim: Easterners, or “Orientals.” They comprised the numerical majority of the Jewish population, but Ashkenazic Jews held the political power. In his 1964 novel, The Ma’abarah [Transit Camp], Iraqi-Israeli writer Shimon Ballas describes the physical, emotional, and psychological feelings of degradation that permeated the squalid transit camps holding the Jews from the Middle East and North Africa. But Ballas also suggests that these camp residents began to regain agency as they turned to collective action. In ways both challenging and inspiring, the transit camps were instrumental in transforming the identities of these Jews, who reclaimed as their own the term Mizrahi, a celebration of their heritage and mark of their political and class consciousness. In addition to expressing opposition against poor living conditions, Mizrahim objected to the demands for assimilation to the Ashkenazic hegemony. As sociologist Sami Shalom Chetrit explains, Mizrahim were seen by Ashkenazim to be in “the stage of transition from undesirable backward Arabness and Middle Easterness into the longed-for stage of European modernity, wherein their dominant Zionist Ashkenazic brethren are already established.” He describes a process of “Ashkenaziation,” and “the erasure of Arabness from the Jews of the Arab world.”

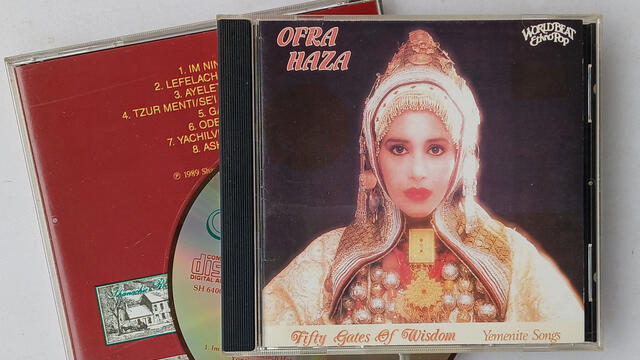

Ofra Haza and the Power of Mizrahi Women’s Voices in Israeli Culture

For decades, ideas about Arab Jewish backwardness persisted in Israel. In 1979, Ofra Haza, a young Jewish woman of Yemenite heritage, sang the song “Shir Ha’Freha” in a film called Shlager. The narrator of the song describes herself as caring only about lipstick, nail polish, dancing, and showing off. Freha is often translated as “bimbo.” Essayist and fellow Yemenite Israeli Ayelet Tsabari contextualizes it as a common slur almost always reserved for Mizrahi women; her essay “A Simple Girl” explores the damage resulting from such language as well as her desire to see in Haza’s song a cry of resistance. This claim can be debated, but Haza’s fame cannot. She won second place in the Eurovision song contest, sang with Iggy Pop and Paula Abdul, and played in the film The Prince of Egypt. Haza also gained an international audience for her traditional Yemenite Jewish music, a historic triumph that paved the way for other Mizrahi artists. Using fiction, music, life writing, and photography by Iraqi, Yemenite, Tunisian, and Israeli artists, we will examine different modes of Mizrahi cultural expression and protest.

Discussion Questions

How might the treatment of Mizrahim in Israel have affected the way that they thought about or represented their previous lives, in their Arab or Muslim countries of origin?

How do you see these writers and artists addressing historical mistreatment?

Why do you think Jews from Arab countries were called Mizrahim and not Arab Jews? What do you think about the term Arab Jews?