Judea under Ptolemaic and Seleucid Rule

Conflicts between the Ptolemaic and Seleucid dynasties shaped ancient Judea and eventually led to the Hasmonean revolt.

Great Power Competition

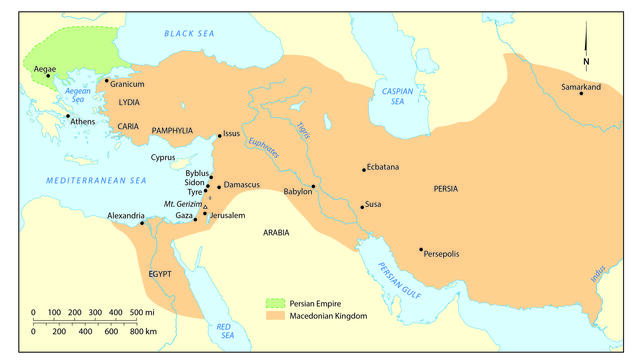

After the establishment of the Ptolemaic and Seleucid dynasties, upon the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, the territory between the Mediterranean and southern Syria was a site of regular conflict, the result of competing claims to the territory. This area was commercially valuable because of its location on the Mediterranean Sea and because it served as a land bridge between Mesopotamia and Egypt. As a result, the great powers of Egypt and Mesopotamia often competed for control over it.

The Seleucid Empire and the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt fought over this region in the six Syrian Wars, between 274 and 168 BCE. The Ptolemies maintained control over the area until the fifth war, which ended with a conciliatory treaty between Antiochus III (r. 223–187 BCE) and Ptolemy V (r. 203–180 BCE) in 200 BCE. (Literary evidence for the dating of the Fifth Syrian War is limited. Although it is often dated to 200 BCE, it is a matter of debate among scholars, some of whom date it two years later.) Coele-Syria—as the territory was redesignated by the victors—came under Seleucid rule. These wars meant that the majority of Jews were, after Alexander’s death, subject first to Ptolemaic and then to Seleucid rule. Under both, though more speculatively with respect to Jews under Ptolemaic rule, Jews and some other non-Greeks maintained a high level of self-rule and freedom of worship.

Ptolemy in Judea and the Rise of the Tobiads

The Tobiads emerged as an important clan during the reign of Ptolemy II (r. 285–246 BCE) and remained prominent in the decades leading up to the Hellenizing reforms of Antiochus IV Epiphanes and the Hasmonean revolt. Josephus provides a very long account, manifestly heavily fictionalized, if not simply fiction, and too long to be included in its entirety, of the rise of Joseph, the son of Tobias (the name that Josephus transcribed as Tobias appears in Greek texts as Toubias and in Hebrew as Tobiah), and he informs us elsewhere that the Tobiads were descendants of Tobiah the Ammonite (Nehemiah 2:19). A certain Toubias, who may have been the father of Joseph, appears to have served the Ptolemies as a local military commander in Transjordan, drawing on his own kin and dependents for personnel.

While Josephus wrote long after the events he describes occurred, contemporaneous evidence appears in a letter from Toubias to Apollonios preserved among the Zenon papyri, a trove of documents belonging to the Ptolemaic official Zenon, who traveled through Judaea on behalf of Apollonios, the dioiketes (chief administrator of the Ptolemaic kingdom). While serving as a financial officer in the Ptolemaic administration in 257 BCE, Toubias sent animals as gifts to Ptolemy. If there is any truth to Josephus’ tale about Toubias’ putative descendants, his family achieved additional political influence by cultivating relations with the king and marrying into the high priestly family of Jerusalem.

Josephus’ account, in its details, is of dubious historicity, but the politics of tax collection in the second half of the third century BCE, the cultivation of connections in Alexandria by rising local figures, and the implicit competition between Onias (representing the high priestly family) and the Tobiads—with whom they were also intermarried—have the air of plausibility and so may deepen our understanding of late Ptolemaic internal Judean politics. In this passage, Josephus relates how during the reign of Ptolemy V (a dating that is manifestly a mistake on Josephus’ part), the high priest Onias III refused to pay the Jewish tribute of twenty talents that his father Simeon the Just had paid from his own revenue. Joseph, highly respected in Jerusalem, and nephew of Onias and son of Tobias, went to Ptolemy and diffused the tension. The continuation of this passage describes how Joseph subsequently gained control of the taxes of Coele-Syria, Phoenicia, Judaea, and Samaria. Josephus describes Joseph as an exceptional tax collector, with close ties to Ptolemy. The Tobiads served as tax collectors for the Ptolemaic rulers for at least twenty-two years.

Seleucid Conquest of Jerusalem

After defeating Ptolemy V Epiphanes and his general Scopas in 200 BCE, Antiochus III the Great (r. 223–187 BCE) annexed Judea. According to Josephus (who relied in part on the account of Polybius of Megalopolis), the Jews welcomed Antiochus III and his conquest of the southern Levant, including Palestine, billeting his army and assisting in his siege of the Jerusalem citadel, which was still held by Scopas’ troops.

The Hefzibah inscription dates from the 190s BCE, very soon after the Seleucid conquest of the southern Levant, and pertains to developments from the beginning of the Fifth Syrian War, initiated by Antiochus III’s attack on Coele-Syria in 202 or 201 BCE. Discovered in 1960 about four miles northwest of Beth Shean, this stela presents a dossier of royal correspondence between the military governor and chief priest of Coele-Syria, Ptolemaios (Ptolemy) son of Thraseas, and Antiochus III concerning the quartering of soldiers in the villages, among other matters. Ptolemaios requests that Antiochus III prevent his soldiers from forcibly dislodging villagers and pressing the locals into service. The king obliges. Correspondence between the king and his administrators was often publicized on limestone stelae such as this one.

Seleucus IV and the Temple Treasury

After the Seleucid army was crushed by the Romans at Magnesia in 190 BCE, the Seleucid Empire found itself in financial straits. Second Maccabees relates that soon after this defeat, Seleucus IV Philopater (187–175 BCE) gets wind of enormous treasure in the Jerusalem Temple coffers to which he may lay claim. He sends his chancellor, Heliodoros of Antioch, to take possession of the treasure. In anticipation of Heliodoros’ arrival, the distressed inhabitants of Jerusalem cry out to God for protection. Their calls seemingly are heeded. Upon Heliodoros’ arrival at the Temple treasury, an apparition of the Lord appears, accompanied by two splendidly dressed young men who beat Heliodoros. Although the Jews of Jerusalem are relieved and grateful for God’s intervention, the high priest Onias III prays for Heliodoros’ recovery, fearing Seleucus’ retribution. Heliodoros recognizes God and offers sacrifices, ultimately warning Seleucus against sending another emissary against the Jews and their God.

Context for this episode is provided by the so-called Heliodoros stela, dated to 178 BCE, which preserves three letters, presented in reverse chronological order. The stela features a twenty-eight-line proclamation in Greek in which Seleucus IV instructs Heliodoros to appoint Olympiodoros as the “high priest” in charge of sanctuaries throughout the region. In this role, Olympiodoros would also have been responsible for ensuring appropriate temple revenues and taxes were submitted to the king, including for the Temple in Jerusalem—and its treasury. The Jews of the region may have perceived this appointment as infringing on their own religious autonomy, leading to the deterioration of Seleucid-Jewish relations under Antiochus IV Epiphanes (r. 175–164 BCE).

Read next: The Hasmonean Revolt